Obsessive encounters

A case study from Mallorca on language and fetishization in tourism

urn:nbn:de:0009-10-52683

Abstract

This article is about travel as transgression, pilgrimage and fetish. It bases on empirical research conducted by the authors at now-closed sites of transgressive party tourism in El Arenal on the island of Mallorca. Constructions of transgression and lostness are seen as being complex: Getting lost while traveling is regarded as part of the scripted confusion in the tourist zone. We therefore investigate the noise in the beer halls as opportunities for the tourists to create meaning in situations when one does not know how to articulate oneself properly. Instead of leading to destruction, the lack of ordered language, we argue, serves the reification of order. Through the production of ambiguity and meaning, community could be created. Despite the abrupt halt of the tourism industry due to the pandemic in 2020, this need for ritual transgression and community making did not disappear. By its unavailability, the outcry for the rituals became even more channeled on digital platforms. Soon, products were sold online that should help to replace those which could usually be found in the shops in El Arenal. Implementing the consumerist part of the imaginary of adventure, the items further deliver the previously performed mockery of the marginalized to the holiday makers in their home apartments. The ritual transgression by tourists at the Spanish party site always involved giving a role to West African migrants. As ambulant vendors, by wearing carnivalesque costumes and selling items such as sunglasses, they were to offer moorings for order to be restored, making racism and segregation along the boundaries constructed by classism obvious parts of the consumption and excess in the area. The street vendors, who could before at least slightly benefit in a financial way from their inclusion in the party industry at the beach, were then completely bypassed by the online T-shirt sales, and the hostility of the images representing them increased. We argue that, with reference to Walter Benjamin, these transgressive objects at the cost of marginalized and precarious Others were necessary for the upholding of ritual confusion and the following reinstallation of order.

<1>

When Walter Benjamin wrote about how “the tradition of the oppressed teaches us that ‘the state of emergency’ in which we live is not the exception but the rule” (2003 [1940]: 392), he might not have thought about viruses and how they infect bodies and capitalism alike. But some of us whose lives were suddenly affected by the virus in spring 2020 thought about Walter Benjamin and this famous quote, and how it now, finally, was us (and no longer the postcolonial Other, for that matter) who experienced how fragile order was and how quickly it gave way to confusion and the state of emergency. For a moment, a different perspective on history became plausible, where representation, to put it in Michael Taussig’s words, must be understood as “contiguous with that being represented and not as suspended above and distant from the represented” (1992: 10). Signifiers abound, and to decipher them required the knowledge of the sorcerer or the shaman, so that all we could do was to wait it out. But waiting was of a strange kind, in this sudden reality of ongoing ruination. It was rather being under siege, as time stood still, and that even more proved Benjamin right:

[…] because in a state of siege, order is frozen, yet disorder boils beneath the surface. Like a giant spring slowly compressed and ready to burst at any moment, immense tension lies in strange repose. Time stands still, like the ticking of a time-bomb, and if we are to take the full measure of Benjamin’s point, that the state of siege is not the exception but the rule, then we are required to rethink our notions of order, of center and base, and of certainty too – all of which now appear as state of sieged dream-images, hopelessly hopeful illusions of the intellect searching for peace in a world whose tensed mobility allows of no rest in the nervousness of the Nervous System’s system. For our very forms and means of representation are under siege. (Taussig 1992: 10)

The state of emergency was indeed one of siege: lockdown, planes grounded, stranded in everyday environments. Hence one was unable, for the time being, to partake in academia’s mobilities: the conference sites of the knowledge industry, where we could realize our fantasies of world-as-order and as something that could always be explained. As if there was no doubt about the relation between the two, the same largely happened to the fantasmorganic world promised by the tourism industry.

<2>

Siege produces, in quite foreseeable manner, images and tales of radical inversion. Cockaigne and carnival are both concepts of an overabundance that is closely related to order, which made them utterly fitting in this state of emergency that resulted in a long wait for reality to return. The plentiful of regalement and the ecstatic moment of inversion, they both base on the idea that there is order that is reliably there, authoritatively defying the emergency state and keeping reality under control. To act against it, indulge and transgress, even the mere thought of that, renders more visibility to it than any adherence to its rules. Siege quickly gives way to narratives of normality, in which normality is no longer the state of emergency, but a world in which that which puts us under siege is under control.

<3>

On the island of Mallorca in Spain, which had been a summer tourism destination of German holiday-makers so popular that its government had implemented regulations to keep tourists away, the provisional end of the siege was met with transgression. After the outbreak of the coronavirus, the return of the first tourists to El Arenal, one of the island’s busiest party locations, in June 2020 provoked even more inversion narratives, in a curious twist of how order manifests itself. What seemed as a radical reaction to the siege, namely the partying masses getting drunk in the congested environments of the clubs and beer halls, all without masks in spite of the virus still hovering in the air, produced precisely the reactions it had to produce: calls for the return to order, the state’s order. Like any carnivalesque practice and like any site of such institutionalized transgression, intoxication resulted in its counter-image, namely sobriety. The clubs and bars were quickly closed down again, with uncertain future. The heralds of such return to order had already been visible before: press images of the crowded streets in the party quarter not only had shown unmasked tourists, but also their suppliers of things and of performance, the young Senegalese men selling plastic sunglasses and imitated Swiss wristwatches. These young men, being so much more than merely street vendors, heralded the annihilation of the state of emergency by wearing spotless white captain’s hats. And thus adorned with this emblem of state power this land-locked navy of “beer captains” [1] navigated the masses of tourists through their performances of transgression. Our own navigation through this transgressive space and practice included methodological approaches such as walking (O’Neill & Roberts 2020), reflection on mimetic performance (Ladwig & Roque 2018) and interactions with material culture (Shepherd 2013).

<4>

The presence of the Senegalese participants wearing such head gear almost seemed to double the annihilation of the siege. Not only was everything normal again and in good order – the party zone had been opened again to its clients – but the protagonists, such as the stigmatized West African vendors had been made captains, who guaranteed good order by remaining in their marginalized position, but at the same time guaranteeing that this was the order that was meant to be kept. These captains appeared to look reliably after the maintenance of their own marginalization and as competently after their clients’ fulfilment. And because the lives of the oppressed and marginalized do not seem to count much, as we know from Benjamin, the end of the spectacle had already been planted into the spectacle itself. When the bars and clubs were closed down by the government as a reaction to the risk of virus spreading, the commodities that were needed to celebrate transgression and thus order elsewhere had already been put on offer. The motto T-shirts that are an important part of tourist performances of transgression as well as of talking possession in El Arenal were normally sold by the many shops along the beach promenade, mostly by Indian or Pakistani businessmen who carefully monitored the soundscapes around them and the social media production referring to the party site, in order to quickly design ever new motifs for their shirts on offer. This coronavirus year, tourists would not travel to the island as they did in the previous years, and bought their party shirts from internet shops being quick in supplying party mimicry at home, for example with prints about how one’s own balcony this time replaced the playa (Mallorca is calling and I will stay home [2]). In order to get ready for a summer in parks and on balconies in their every-day environments, people were offered a shirt with the print Ausnahmezustand ‘state of emergency’ [3], with a double entendre signified by its rainbow-colored design. Another shirt on offer bore the print Corona egal ‘Covid-19 I don’t care’ [4], again ambivalent, as it could both be an ironic remark on those who didn’t seem to care, or a statement of one’s actual ignorance of the siege.

<5>

There were more T-shirts than before with prints that referred to the Africans at the beach. Thus, while being at home, one did not have to miss them, who had no means and no documents enabling them to move on into similar seemingly safe environments. And hence, the tourists who remained locked out of their holiday paradise were offered the image of the Other on their bodies. While the inhabitants and visitors of other Mediterranean islands were publicly discussing how to create safe environments for migrants during the pandemic, the T-shirts bore imitations of imitations of vending cries, the name given to the Africans on the beach (Helmut), racist language and an image of a Black face: Uncle Helmut – do you need sunglasses [5], Originale Helmut with a racist image underneath [6], the combination of a pineapple and Helmut [7], and so on. Partying back home, the ceremony was not only about the affirmation of order through one’s own intoxication, it also involved the destruction of the Other. The pandemic called for a racist performance of exclusion of all those who had now, in coronatimes [8], better stayed away. Reification of the state during the state of emergency also involves the rejection of the migrant. The crisis is absurdly clarifying the previous norms. This is how we did with a guest and will continue to do. What kind of host is this who wears the distorted image of her or his neighbor on the body? What kind of space calls itself part of the hospitality sector while it is celebrating manifested separation? By buying and wearing a T-shirt with such a print, a certain hegemony was again performed and installed. While tourists could easily discriminate against migrants from afar or even digitally, the latter in turn were playing football at the emptied beaches while waiting for the tourists to return to them.

<6>

Travel is a form of displacement and a disorienting experience of rupture and transgression. We argue, in the context of mass tourism, and very visibly in party tourism, it bears in itself the power to reify order, which – because travel leads us to Othered places – also is a colonial order. We furthermore argue that the objects and images – such as the T-shirts with their ambiguous prints – claim the position of magical objects, as they, through prints, labels and other signs put on them, become more powerful than power itself. They must be earned, understood and not at least be bought. As that what is often referred to as the souvenir – a misleading term, as these things can just as well be acquired in the home, by ordering them in internet shops – these objects are closely connected to travel, but at the same time refer to the home and the orderly. And this is where we enter the realm of the fetish. In a chapter on the maleficium, Taussig looks at fetishism as state fetishism (1992: 111). The constructed thing called society and the sacred objects through which it speaks, Taussig says, share a particular relationship, in which society “was blocked, silenced, and the discourse bounced back into the object’s design and substance. That’s what made them fetishes.” (Taussig 1992: 140). Turning to the party tourism site, that ultimate vision of capitalism and colonial exploitation, and to the objects it needs to be complete, there is a possibility not simply to explain the ways in which these objects trigger performances that affirm the order they seem to put into question, but also to understand how these things become fetishes of order. Taussig, citing Pietz’ study on the genealogy of practice of the fetish (1985), emphasizes that the meaning of the object’s name itself needs to be considered: maleficium ‘badly made’ and the ‘making’ as in “fetisso in the Portuguese pidgin trading language of the West African slave routes” (1992: 118): “This amounts to a European history of consciousness making itself though making objects, and this involves a compulsion to fuse and separate and fuse once again the maker with the making with the thing made, wrestling with poignancy with what we might call Vico’s insight, which is also Marx’s – God made nature, but it is man who makes history and thus can come to understand this by understanding this making.” (ibid.). Hence, travel, as adventure and as a commodified object, already has to entail such making, namely of order, in turn suggesting community, and in ways that we might consider special, unusual and, perhaps, strange. Being thrown into situations that offer little means of reflection and relation to the people around makes us lack language, using just the wrong words, and turns our bodies into strange places on which our clothes look unbecoming and in need of ironing. There is no time for ironing, however, and no space for irony as well, as we move on. Travel, no matter how far it takes us, moves us away from where we know how things are done and how life is going on. And finding one’s way elsewhere is not only a matter of finding ways of knowing what to do, but also of finding ways to an understanding of how these other places are organized and how one can move around in them. This, we want to argue, is crucial, because there is a need for confusion in travel, and a desire to experience joy and lust in adventure. In his work on Bewildered Travel, Frederick Ruf explores different possibilities in making sense out of adventure and travel, engaging with its spiritual side:

That what travel means is not just misfortune but seeking misfortune. In some sense, wanting it. And it is of such crucial importance to us that we must call it religious. Leaving home, stepping into the way will lead us away, far away, walking among strangers, being stunned, getting lost – those are religious behaviors. (Ruf 2007: 4)

Ruf (2007: 170) calls the places the traveler-pilgrims go to homeless places, places that are meant to accommodate those who can never fully belong to them. Such homeless places are, according to Ruf, hotels, as well as sites (of any interest, as sites that can be visited), the street, and the body. All these are merely places of temporary importance, and cannot be turned into a home without being removed from the adventure and pilgrimage. The homeless place is even necessary for fulfilling the pilgrim’s need of liminality that is within the process of leaving your well-known everyday surroundings (Wöhler 2011: 246). Leaving the structures of a home liberates oneself from its boundaries and enables the pilgrim to transform, only to remake her- or himself. Such homeless places have been called non-lieux, ‘non-places’, by Marc Augé in his critique on the desemiotized spaces of ‘super modernity’ (surmodernité; 1992). As dimensions of networks and the acceleration of travel increase, visual and imaginary connotations multiply, Augé argues, place increasingly turns into a temporary thing: a mall that is closed after shopping hours and then falls silent, a waiting room in which not a single word is spoken, a parking lot. Augé’s non-places are characteristic for multi-national networks such as the tourism industry, urban transitional spaces, as well as contemporary Edgelands (Farley & Symmons Roberts 2011). In non-places, community exists as the quick and evasive, resulting from a mutual experience of difficulty and misfortune (such as being mugged, a fire alarm, or an accident). They are where adventure takes place but no home can be found – sites of liminality (Roberts 2016). Non-places are sites of an overabundance of individual references, of the noise of particularity – not of communality and concerted speech. Yet, they are deeply contradictory places that can always be claimed back and turned into homes. Postcommodity, a cooperative of Indigenous American artists, has demonstrated through various performances how a motel room turns into a communal place through slaughtering a sheep in its bathroom, or how a depopulated border region may be filled with ancestral presences through its remaking by an installation of colorful balloons (http://postcommodity.com/Work.html).

<7>

The contradictory of the homeless place and our yearning for confusion while we are traveling to such places is in itself displacing. This paper aims at exploring the politics of contradiction which were present in tourism places including all participants (migrant workers, local inhabitants and the tourists themselves) and mass practices that made reference to religious meanings in various ways. We argue that transgression and confusion is part of a form of pilgrimage that sustains mass tourism sites where party tourism and sex tourism take place, where people seemed to deliberately ‘lose control’ within a controlled colony that bore resemblances to previous colonies, with emblems of the colonizing nation state firmly put in place. In spite of the transgressive practices of the German tourists and the quick, messy and unstable encounters they have had with those surrounding them – Senegalese street vendors, Brazilian Capoeira artists, Hungarian table dancers, Nigerian lavatory attendants and sex workers – there was meaning in these encounters, and a means of engaging with each other that enabled participants to mimic social order that resembled that of a colonial metropole.

<8>

In the following sections, we describe how the messy and the noisy were made sense of, and how scripted confusion was at the core of the reification of a communal order industry – one which people often do not wish to be associated with. This pilgrimage site obliged to accept the roles imposed on its visitors, and to wander within its boundaries on fixed paths (Storch 2017). Our descriptions therefore provide a view from within, nothing more.

<9>

In the Bierkönig, one of El Arenal’s then largest party venues, guests were engaging in communal drinking while they sat on bar chairs or stood around tables. On these, large glasses filled with beer, vodka-lemon, or sangría could be seen, as well as glossy colorful show flyers, confetti, and the guests’ mobile phones. The phones were essential, as they were used to repeatedly take pictures of what was there. This was the first step of integration: when the tourist entered the drinking hall for the first time, he or she was likely to be overwhelmed by the masses of people and the noise. To reduce this feeling of being extradited, the scene could be objectified and therefore controlled through the lens of the mobile phone’s camera. Instead of looking around helplessly, one could seem more confident in doing something practiced very well: taking photos. And even more than this, photographing the overwhelming and confusing place is also a creative act, an act of creating one’s own Bierkönig. However, the control over the situation and the location that was expressed by photographing the scene with the mobile phones was not only an act of self-integration, but also one of separation. As the drinking halls were zones that were only to enter for customers who were able and willing to pay, the celebration of its condition by manifesting it in a digital photograph demonstrates the acceptance if not favoring of the exclusion of a group of actors that is otherwise very present in the tourist zone: African migrants that are working as street vendors.

<10>

By the time the guests filled the Bierkönig’s halls and balconies, they had already spent time at the beach or pools, sleeping and resting, eaten a super large Bratwurst, or enjoyed a Mediterranean dish instead, and then had resorted to their nearby hotel rooms in order to have a shower or change into another t-shirt. Some tourists might have worn party hats, colorful wigs and costumes, while others came as a group of which each member wore the same motto T-shirt designed for just this trip. Huge screens mounted high above the tables showed football games, and out of the ubiquitous loudspeakers blared German party songs. Some people sang along. In between the tables, there were other, more massive tables, which were not meant for standing at, but which were the stages on which table dancers performed. They looked different than the tourists, with their tanned skin and lingerie outfits. Each table dancer exhibited bundles of Euros held by her garters, which seemed to be meant to encourage the guests to add yet another bill to the sum. The table dancers always danced in pairs, for about ten minutes, until they were replaced by colleagues. They performed in relatively uniform ways, dancing reluctantly on high-heeled shoes. Sometimes they sang along to the songs, too, creating a feeling of being ingroups with the tourists. Suddenly, after his favorite football team had scored on the giant TV screen in front of him, a young man climbed on top of the table at which he had stood and imitated the movements of the table dancers. While he wiggled his bottom and shook his hips and chest, his friends handed him a wooden phallus, which served as the handle of a bottle opener. After removing his shirt and his pants, he fixed the phallus at the front of his underpants and attempted a form of table dancing that was yet more celebrated than the professional dancers’ performances. People on the balconies and at the tables of the ground floor applauded, yelled, and photographed the scene with their phones. What was a form of invasive violent appropriation, was at the same time part of a play that combined a ludic setting (dancing, sport shows, etc.) with performances of virile power (Andrews 2014).home – After a short while, the man climbed down again, with an expression on his face that might well have been relief. He raised his fists, triumphant as a football player, and moved his pelvis back and forth, a gesture of both sexual dominance and happy sportsmanship.

|

|

|

Image 1: Dancing table, off-season (photo JT) |

<11>

A bit later, a young man climbed the stage of a table dancer and joined her. Once he was safely on top of the table, he removed his shirt and rubbed his chest on the dancer. She led him in the dance, but then also seemed to be led herself by her client’s readiness to either move or to stand still. This was a messy performance, which had no climax. The man went on with his dance simply as long as he managed to, and was finally hugged by the dancer, whose turn was over as she climbed down from the table. This time, not many phones were held up to take a photograph. The football game had become a bit lame, and most guests watched it, with bored looks on their faces. The table-dancing man, however, expressed his excitement – fists raised, hips moving.

|

|

|

Image 2: Dancing stage for customers, off-season (photo JT) |

<12>

Performances continued through the night, while guests were getting more and more drunk and consequently found it increasingly harder to climb the tables. Heightened dancing platforms with railings and more space to move served as an alternative (image 2). They were not used by the professional table dancers, but were located close to them. As before, men performed gestures of dominance and triumph, while dancing to party music with German lyrics and shouting or singing along. Long after the actual football match had ended, the screens continued to show scenes from matches – hour after hour, night after night, year after year until the pandemic.

|

|

|

Image 3: Posing on the dance platform, high season (photo AS) |

<13>

Only rarely women other than the professional dancers climbed up these tables and stages. This was something for men, something that needed a possibility of a wooden phallus and a manly sweaty chest. And this was rather remarkable: while posing on a staircase, stage or bar in a club was nothing special and shared by young women and men alike, El Arenal’s party locations appeared to work in different ways. They were spaces of hegemonic masculine selfing, through heavy drinking and the creation of an eroticized environment. Hazel Andrews (2009) demonstrates that not only the spatial organization of these tourism sites affirms (and constructs) masculinities along stereotyped national identity concepts, but also the ways in which places there are named: Lord Nelson, Duke of Wellington, Robin Hood.

<14>

In the Bierkönig, such emblematic signs were, for example, the frescoes that depict stereotypical scenes of heroic drinkers in German attire. Yet, by turning the gaze at where and with whom precisely performances happened, the semiotics of place are revealed to be rather complex. What first appears to have been an orchestration and embodiment of the heteronormative masculinity, which is conveyed in the symbols of Magaluf as Andrews (2009) attests it, turns out to be more confusing and messy when looking at El Arenal and the Ballermann. Rather than observing the table dancers and cramming Euro bills onto their garters, the clients watched sports and sang along to the – often misogynic – party songs that filled the entire area. There seems to have been no clear designation of what to do at these places, apart from the consumption of the drinks offered by the bar: how was this presumed heteronormative space filled with practice, and which interactions took place between the table dancers (among other women who work in the clubs and bars) and their presumed masculine audiences? Visitors to El Arenal who posted comments and advises in digital chatrooms and commentary sections of websites on tourism in Mallorca focused on accomplished practice, as a fulfillment of various promises – beach, sun, sex, and some kind of organized space:

Naja, unser Urlaub in kurzem: Bis mittags geschlafen jeden Tag, dann immer den ganzen Mittag an den Strand gelegen ( der im Übrigen total sauber war), die hübschen Frauen betrachtet, die meistens fast nichts anhatten ;) , Abends dann in eine Disco gegangen.....

Was mir auch noch auffiel: es war echt net viel los am Ballerman...Klar waren die Discos immer relativ voll, aber am Ballerman hät ich noch viel Mehr Leute erwartet....

Fazit: Wer einen günstigen Urlaub zum Saufen und *Sex haben* möchte, der is am Ballerman bzw. in Él Arenal genau richtig...

Well, our holiday was essentially about sleeping till noon, then going to the beach (which is very clean) for the entire day, watching the pretty women there, who, by the way, were hardly dressed. In the evening we went to a disco ... I realized there wasn’t a lot going on at the Ballermann ... of course the discos were quite full, but I expected more people to be there. Conclusion: whoever wants to spend a cheap holiday of drinking and having sex will be happy at the Ballermann or at El Arenal.

(Chris, http://www.ciao.de/Arenal_Mallorca__Test_2737412; our translation)

Yet, how were the promises of easy erotic encounters kept which were made in this and countless other travel guides and chatrooms [9]? How was it that the spending of money for the consumption of people and things was the main act on this holiday stage but, nevertheless, the tourists did consider it an experience that was cheap or would even save them funds? The homeless home was a place that offered contradictory experiences rather than clarity, in this case the beach, the promenade and the surrounding locations. Learning how to make use of the place did not seem to take place in these explanatory blogs and chats, and the Ballermann itself did not seem to provide any guidance, as in the form of signs and texts, either. What needed to be known in order to make actual use of the site and its offers had been learned already, and was nothing but the secret at the base of any state power (Taussig 1999). This was adventure, maybe: setting out for conquest and for frenzy, and yet not having any guidance to how this might have been achieved. But there was shared practice, and there was sense in all this. In contrast to also having been homes to many tourism workers like street vendors and shop owners, the beer halls, the bodies, the Bierkönig as a tourism site, and the street in front of it (which is called Schinkenstraße ‘bacon street’) all interacted. As the homeless places that they were, they did so in obscure and messy ways.

<15>

Walking up the street, in a party costume, buying a colorful hat from a street vendor, ecstatically yelling the chorus of a schlager hit in the streets, entering the bar and rubbing one’s homeless body with other bodies was part of a pilgrimage that might lead to newly confirmed manhood, to friendship restored or to some newly built outlet for frustration and estrangement. And not written text, but built environment and performance served as means of the transmission on knowledge on how this pilgrimage needed to be done. One walked, like on other pilgrimages, just where the others walked and went where they went. We might not have known where this led us to, but soon we understood: into the club or the bar, where loud music created a bubble of sound that encapsulated a place and segregated it from another. Once inside the bar, there was abundant performance: football players on the screens, table dancers on their table stages, partying guests with their smartphones and motto T-shirts. As the football players, who were mere images on their screens, the table dancers were not meant to be approached for intimacy: they were professionals, they came from far and were casted in order to provide not sex, but to create and yet repress the lust for it. Their flawless bodies and perfectly cool dance moves did not invite to go wild, but to create fantasies and discipline the transgression that’s there. Dancing on the table with them was meant only for special moments – after a football team had scored, a group had consumed a certain amount of alcohol, social bonds had been affirmed. This encounter needed to be earned and was a fulfillment in return. The dancers’ movements guided the clients in their performances, and this as well as the fact that they shared their workplaces with them for these very performances hints at the processuality this pilgrimage was about at this stage. Manhood here was contradictory – virile and heterosexual in its outward construction, and yet gender-bending in the way individual performances seem to intrude into the women’s place: the tables they danced on and the bodies they presented there. Communities of men – Männerbünde – have the potential in them for a play with gender constructions, for other possibilities of sexuality and identity concepts (Brunotte 2004). Here, precisely this was enacted, as performances were transgressive and – like passage rites in religious contexts – bound to a place and a context where they could be bought. As nevertheless, access to the stage had to be paid. Although there was no entrance fee which suggested a welcoming environment, those people who were unwilling to buy a drink soon enough would be ushered out again. Men could drink a tower of vodka lemon here, climb tables, undress, play with wooden phalli, but they could not do this elsewhere than at this homeless pilgrimage site, not in Mallorca’s other tourist sites and not at their homes. Upon performing transgression and messiness that was somehow bought from the space they performed the detachment from their previous personae and created possibilities for releasing a liberated such with new optionalities, which were played out later, in the streets, hotel rooms and chatrooms.

<16>

The table dancers as professional and disciplining staff did not participate in these transformatory practices. They worked according to a strict schedule and remained flawless icons of objectifying desire.

Most of the dancers came from Central European countries like Hungary or Serbia to work seasonally in the drinking halls. Even though some of them had been dancers before, work experience was not really necessary. The dance moves could be learned easily; the challenge was in the way one needed to look at prospective clients, in order to attract more customers, and in the emotional work done by the dancers, imposed on themselves and the tourists alike. A friend usually introduced them to the organizers of the clubs, where they were casted for dancing shifts that lasted for six or twelve hours a day.

<17>

Wosick-Correa & Joseph (2008: 208) describe the concept of a front, back and side stage in conventional American strip clubs, as an advanced model of Goffman’s (1959) theory on how people present themselves differently in social contexts. The front stage includes the acts the customer is allowed to see, the spaces named back stage are keeping everything else from the customer’s eyes like locker rooms or staff rooms, where the putting on of make-up and clothes takes place, while the side stage are the spaces in between, in which an unforeseen overlap can take place, e.g. the women’s bathrooms, which both strippers and female patrons would use.

<18>

The most crowded clubs in El Arenal were not devoted to making profit from the dancers mainly. Instead, they served as a side attraction to pay attention to in special moments, which were clearly distinguished and must be respected. Their front stage was placed on top of the tables. Here the dancers interacted with the tourists not only by motivating them to move their heated limbs but also created a communal feeling by singing along to the songs with them from their lifted stages. Most of the dancers said that they were not aware of the content of the German lyrics, but since they were based on monotonous and catchy beats and played repeatedly every day, it was easy for them to lip sync to the songs.

<19>

At the front stage (or up stage respectively) the emotional work of designing an atmosphere that was pleasant to the customer was described as exhausting by some dancers. The uncomfortable high-heeled shoes, the drunk people and the noise were the most often named challenges the dancers had to cope with while creating an inviting atmosphere for the visitors, something that is compared by Wood (2000: 22-23) to the relationship between air hostesses and passengers during flights. Here, at the club, the customer was checked on regularly, animated when bored and cheered for if he accomplished a task. The dancer’s job is described as making the customer feel being cared about, while creating a sensual attraction which gives the impression of the possibility to an even more intimate interaction.

<20>

Asked whether she liked her job that largely served to pay for her studies during off-season, one dancer shouted ‘no!’. Further asked why, she said: ‘Just look around and tell me what you see. How could one just find pleasure in this?’ This dancer’s emotional work can be found in the up-stage performance of caring while hiding one’s own differing feelings. Downstage (or, backstage), the customer was taught to respect the dancers’ personal space. While up-stage getting close was asked for, as soon as the dancers stepped down the table, their being on eye-level with all the customers in their extraordinary appearances (high heels were uncommon amongst female customers) suddenly created not only admiration but also an aura of intimidation. Now, off their duty, they certainly would not be touched or talked to anymore. Only rarely groups of men were seen asking for a selfie with them. Conversations or attempts for more intimacy were unusual in this situation, until the break was over and the next song must be danced to.

<21>

At the party zone, which was felt as a place where no boundaries existed, such inhibitions appeared contradictory. Visitors to the clubs and bars mockingly addressed this by referring to the enclosing and restricting space of the tourism environment by presenting themselves as potential yet unsuccessful transgressors. Much of these mocking and ironic comments were made through posts in the social media, very often in the form of “confessions”. One outlet was a facebook page called Ballermann Beichtstuhl (‘Ballermann confession’, facebook.com/ballermannbeichtstuhl), where memes as the following one were posted:

|

|

|

Image 4: Ballermann confessions |

<22>

The text in image 4 addresses boundary violations by drunk clients of the Bierkönig, where many table dancers worked: ‘I (male, 27) confess that at the Bierkönig the party king of our soccer team stuck his finger into a dancer’s botty. She was very much appalled.’ The male client is portrayed as a buffoon, who, once sober, will be ashamed for his silliness, while the dancer is presented as typically passive and unable to cope. This is largely achieved through the use of words such as Popo ‘botty’ and erschrocken ‘appalled’, which would be employed normally for more innocent and childish tales.

<23>

In a similar manner but still different, though, worked the online reflections of encounters with the African street vendors who were usually named Helmut. Videos of mostly male tourists were uploaded on social media channels which showed them together in a group with usually only one street vendor who was dressed up and presented his sales songs in German language. The tourists would usually laugh about him and then name him ‘my brother’ or another familiarizing term to suggest personal closeness. However, this familiarity would end very soon – most likely directly after the video recording was finished – but definitely when the next bar was entered in which the African vendors were not allowed. Besides the racist and ridiculing aspects, these videos contain another layer of deviancy. As it has become part of the communal knowledge (which will be elaborated on further below) that Helmut is the ultimate Other (Traber 2020) – unable to be attractive for women, disturbing everyone who is having a good time, absolutely unintelligible, producing unwanted noise etc. – the public self-representation with him is a self-mocking of the tourists. Just like in image 4, the male Ballermann visitor not only appears as a fool but admits himself to be one. Asked about why they nevertheless agreed many times to participate in these videos, a common answer by the Senegalese street vendors who are enacting the role of Helmut was that for them it was a profitable business marketing option. If they became known as good partners of the tourists, they might come back to one individual vendor who could then make a little more profit. The entering of the party zone clearly meant entering work mode. Some individuals were strict about it even up to the point that they refused to speak to other Africans in El Arenal unless they were willing to pay them for their time. This shows that the street vendor’s appearances in the tourist’s videos are far from representations of migrants without agency, although we can also surmise how competitive and rough the work of the street vendors was.

Nonsensical words: bodies and shirts

<24>

Noise was everywhere in this place. Language at the bar was noise, not orderly speech, but yelled fragments. This was not left without a comment, but had received considerable attention by musicians and artists who worked at the Ballermann and at similar locations. Languaging that consists of the use of a few emblematic words, yelled, whispered, is the theme of the hit song Hulapalu by Andreas Gabalier (2015). The song tells the story of an encounter on a dancefloor. It is hot, noisy and the singer obviously hopes for sex to emerge out of this:

|

Hodi odi ohh di ho di eh |

Hodi odi ohh di ho di eh |

|

(Gabalier 2015, also see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lHZtcC67yrY; our translation) |

|

Language, like performance, here turns into confusion. Whether there has been any outcome of the encounter is left as opaque as the meaning of the song’s title, Hulapalu. These nonsensical words are all we will understand in all this noise and heat, the song seems to tell us, and yet, in a contradictory manner, the text was remembered, and the song sung by all who visited the Ballermann.

<25>

The song’s first lines thereby stand in a long tradition of nonsensical words in popular culture. Joel Kuipers (2007) situates doowop music and silliness in language in ritualized performances of counter-culture – as in passage rites, contexts of secrecy and social boundary making. Such texts, Kuipers (2007: 559) suggests, only on the surface treat the nonsensical in language as an accident or a result of distracting noise. Rather, he argues, is this noisy in itself, as a performance that seeks to disengage from the controlling, fixing grasp of the state on language:

How do these flare-ups of linguistic silliness and nonsense have their roots in beliefs about verbal seriousness and sense? We are familiar with some of the Western story of how the sensible, comprehensible character of language was constructed: Western Europeans moved into Africa, America, and Asia in the 1600s and 1700s and encountered unintelligibility on a scale never imagined before (Bauman and Briggs 2003). Projects of bureaucratic state-building required tidy language, with clear, transparent meanings, dictionaries with fixed references, a common shared vocabulary.

Hence, words such as Hodi odi ohh di ho di eh and Hulapalu stand in a rich tradition of ritual incomprehensibility, like words used in trance contexts, in ritual secrecy, and so on. As an example, spirit languages used in possession cults exhibit an equally rich repertoire as playful nonsensical language. Foreign elements and invented language consisting of emblematic features, morphological manipulations that resemble those of play languages, embodiment and performativity may all come together here. And as in other forms of ritual unintelligibility, spirit possession rituals and their respective communicative features are deeply meaningful, for example by being expressions of experiences of cultural mobility (Storch 2011). Gabalier’s song in a playful way addresses such connections and relationships shared with other forms of deliberately unintelligible language, as it locates Hulapalu – the erotic promise that remains untranslatable [10] – in a hot space of transgression and trance-like dancing. This was not simply about drunk people babbling away, as common representations suggest (for a critique c.f. Mietzner 2017, Traber 2017), but language turning into religious revelation.

<26>

After Gabalier’s song turned into a major hit in 2015, its nonsensical lyrics emerged not only out of people’s mouths, but also out of rather noisy objects. The Hulapalu motto T-shirt was since then constantly offered by the many souvenir shops at the beach which were operated by Indian traders, who also designed motifs for T-shirts and caps (Storch & Nassenstein 2020). The T-shirt, as well as loudspeakers playing the song, were means of knowledge transmission. Like the table dancers, they did the work of providing enskillment: knowledge on ritual transgressive practices were provided in messy yet ubiquitous ways. It was hard not to be affected by this noise and confusion, and through the immersion into the nonsensical and bewildering we seemed to become part of it, as players who delved into a spiritual experience of inversion.

|

|

|

Image 5: Ritual unintelligibility on a T-shirt (photo AS) |

<27>

Hence, in spite of the messy soundscapes that were so salient at the Bierkönig and other bars, language did play a role there. It was rich in opacity and appeared to work as a means of creating community, through exclusion of clarity and order affecting everyone alike. It seems important to consider the notion of soundscapes here: language very much belongs to objects, the places where they can be found and the emotions that are held for or against both the former. Noise thereby can be conceptualized as the noise of the other, coming from a social space that is somewhere else, and that characterizes the non-place as a place that resembles an inversive bubble that excludes, as Salomé Voegelin (2010: 45) comments on such concepts of sound:

Noise does not have to be loud but it has to be exclusive: excluding other sounds, creating in sound a bubble against sounds, destroying sonic signifiers and divorcing listening from sense material external to its noise.

Noise therefore not only marks the place where ritual transgression takes place, but also serves as a signal for forbidding all those who do not participate in the ritual – Senegalese street vendors, for example (Nassenstein 2017). Place was therefore, unsurprisingly, celebrated in many of the party songs that also contributed to the construction of the sound bubble. In one of the successful songs of the past years, which continued to be played, Mallorca (as a synonymous name for the Ballermann and El Arenal) was conceptualized as home, and as what gives sense to life. In Mia Julia’s song, which was typically performed by the artist while she undressed on stage, the homeless home is celebrated as a place the adventurous traveler belongs to and remains at, while bewilderment and inversion do their work:

Du bist der geilste Ort der Welt, bist unser Leben und alles was zählt.

Hier in der Playa sind wir nie allein.

Mallorca, da bin ich daheim.

You are the coolest place on earth, you are our life and all that counts

Here at the Playa we are never alone

Mallorca is my home.

(De Leon & Distel 2015, also see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mMu1hrTcDk8; our translation)

Pointing at where we really belong, contradictorily turning the homeless place, the non-lieu, into a supposed home, and framing fleeting faces as community, teaches the visitor about how to make sense of the confusing and the noisy. This was, it seemed, reality – a reality that marginalized the safe and structured reality that had been left behind at home. And alike, this was where the visitor felt as or even more as comfortable as at home, which was a homeless one. Like a child needs to be educated by its parents inside the house, here more lessons were to be learnt. And like in any other context of knowledge transmission the players might be acquainted with, teaching took place in various forms of mediation. Digital blogs and chatrooms, newspapers sold along the beach, as well as gossip provide insider knowledge that was needed to understand the rules of the homeless home. In return for the efforts made to acquire this certain expertise and knowledge achieved during lessons, the traveler inherited not only the claim for the place itself, but he succeeded by fulfilling his emotional desire to feel rested and homed. The pilgrim’s view on the setting and his ability to enjoy it – despite what might have seemed absurd and unusual to others – established the ownership for its emotional capacities.

<28>

Rules in this place were contradictory in many ways as well. They were inflicted upon the Self, working as a form of psychological control where no control seemed to be in place. And this was crucial: in the era of the smartphone, transgression can be made public in ways that it unfolds a high potential of post-transgressive shaming. Nude performances and sex games in the club or the bar no longer remained hidden from the eyes of all those excluded from these places, but were photographed and filmed, and posted in the digital space (Deumert 2016). And again, noisy objects appeared as means for further enskillment: stickers and T-shirts carried short and idiomatic texts, which were meant to remind all those who traveled into places of confusion and messy practice on the pitfalls and dangers of exposure. And again, these objects needed considerable knowledge in order to be deciphered, and suggested that only those who had already partied and listened to the music and shared joking would succeed.

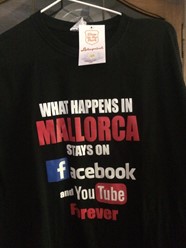

Such objects were not only characterized by opacity; their designs also were complex references to the digital practices that enabled us to be in more than one dimension at the same time. In the summer of 2017, a new design on a motto t-shirt became popular which illustrates how this was conceptualized and translated into practice:

|

|

|

Image 6: T-shirt design that requires insider knowledge (photo AS) |

The shirt plays with font size, font types, and the use of an emoji. Without much background knowledge, the text can be made some sense of: it seems to address the sexual prowess of its male owner, a man whose phallus is supposed to be enjoyable in the context of the place that offered sex as every-day adventure. Yet, there is – in smaller font and in italics – the word ‘tail’ just underneath the ‘COCK’. Does this mean that the genital may be referred to as a tail, maybe? And why was this to be funny, as the emoji seems to suggest?

<30>

To make sense of the senseless, it is necessary to learn about those in whose footsteps one walked while following the rituals of the pilgrimage. In 2014, a video was spread widely in social media which exposed some of the transgressive practices. It was filmed in one of the clubs at Magaluf, a quarter neighboring El Arenal, where erotic contests took place regularly during that time. The winner of the contest in question was a young woman who could orally satisfy more men than her competitors, and she was to be awarded with a Holiday. Only after being publicly intimate with more than 20 men, the young woman had to learn about its’ nature. Against expectation, she did not earn an expensive trip to a foreign country or adventure, but a mixed alcoholic drink that was named Holiday on the menu [11].

<31>

The spread of the visual testimony of this event enabled us to witness several phenomena. First of all, although the party zone of Mallorca seemed to offer freedom, excess and saturation to everyone (Andrews, Roberts & Selwyn 2007), regardless of gender, class and age, the heteronormative practice of slut-shaming was commonly objectifying women only in this context, as could be seen in the commentary section below the posted video. On the other hand, the video lectured the pilgrims of the Mallorca adventure on the boundaries of their freedom. Although the filmed woman was successful in claiming the deleting of the video in court, the story about it was still widely spread in discourse among past and future visitors of the Ballermann, as image (6) illustrates. “Rest assured, no matter what you do, what happens in Mallorca stays in Mallorca!” was a common phrase that followed the laughter that was created by rephrasing the video’s content. The event had become a legend that was told and retold again, often in opaque form, as through the T-shirt shown in image (7), which represents, besides many other things, a warning enough to teach us about the social behavior the place expected from us. A cocktail became a tale, since the practice of the so-called mamading was by the time the T-shirts were printed already prohibited by Spanish law.

|

|

|

Image 7: A warning (photo AS) |

Throwing it all out and up

<32>

Selling sunglasses and other souvenirs at the promenade and on the beach at the Ballermann and in Magaluf was generally forbidden by Spanish law. Doing it anyways to be able to finance their living costs put the West African street vendors in a precarious situation as the police stopped them regularly, took away the forbidden commodities and asked questions about residence permit papers. A different job, though, was not easy to find and then even harder to keep. The media coverage of the tourists’ public nudity, excessive consumption of alcohol and sex parties had resulted in multiple debates about tourism policies and eventually a law as well that was implemented in 2014. Besides restricting the creation of new hotel space, the public consumption of alcoholic beverages and openly performed sexual activities were then penalized. However, forbidding certain practices in the clubs along the promenade had astonishingly not led to a stop of the tourists’ excitement for them just like the numerous police controls could not prevent the street vendors from selling sunglasses and other accessories. Discourse about the legends of the glorious good old times was still alive some years later and created a feeling of being part of an in-group among those who had heard about the same misadventures or even been there themselves. The material representation of this discourse had shifted from images from an online video to a T-shirt print, and the T-shirts again acted as guiding authorities in their form of uniforms worn along the beach promenade and in the clubs. The racist prints that were sold online during the corona pandemic followed the same pattern. By that time, tourists were no further allowed to enter Mallorca and relive the tales they had heard before about Helmut. This restriction had to be bypassed by turning Helmut into just another T-shirt, a palimpsest of the costume someone was wearing in the party zone. Wearing these prints was a way of presenting one’s knowledge about how to find the correct paths through the jungle of the unknown but seductive opportunities delivered by the homeless home even if one was not allowed to enter it, be it for reasons of laws banning specific practices that would constitute the home or of closed borders during a global crisis. In turn, the same applies for the costumes of the street vendors. They wore colorful hats, wigs, sunglasses and clothes and were engaging in loud ritualized sales procedures with their customers. None of these garments, neither those of the tourists nor those of the street vendors, might ever have been worn at one’s actual home. They acted rather as a uniform to indicate the entering of the transgressive zone, physically and mentally. Taken out of their original context they would have appeared silly and possibly even ridiculed the wearer. To establish meaning and present the experience and authority of the wearer was limited to this certain context, either as participant of the transgressing party group or as resilient entrepreneur trying to make a living. This is similar to ritual masks described by Gosden & Marshall (1999: 175): “[…] it was the act of showing which was powerful and which established a mask’s meaning. Possession of a mask was not in itself significant because the mask possessed meaning only in the context of its performance.”

<33>

Presenting oneself as a performance of the mask – whereby the mask was nothing but a cheap garment, and maybe a party hat or a plastic phallus strapped onto one’s body – did not only authorize ritual experience, but also defended other forms of transgressive behavior the individual might have engaged in during his or her stay. The eagerness for sexual outrage that was aimed to be prohibited by the law was presented on another stage. Just like the beach promenade became a catwalk for educative tales and stories presented in a masquerade of obscene clothing, the practice that justified these warnings was banned from the clubs and then staged behind the wall that divided the beach from the pathway. Sex was present in all spheres of perception: the tourists were able to listen to it in the songs, gaze voyeuristically at the uncovered bodies of the table dancers, feel heat and sweat in the overcrowded beer halls and find a lover for short-time intimacy either in the club or with someone selling it to them in the streets. The drinking of alcohol and the consumption of other substances made the players lose their inhibition for normative social boundaries and strengthened the desire for extreme adventures.

<34>

To female tourists who took part in these rituals, the intended transgression took place through breaking with gender roles, such as those of women as being subordinate and as being mere satellites of their male partners at the party zone (Andrews 2009). Being at the Ballermann, the pilgrimage community offered them a temporary inversion, which permitted to shun increasingly stigmatized roles – the housewife, the objectified sexualized woman, the inferior young girl. Instead of staying in a segregated environment, taking part in practices which are commonly conceptualized as masculine (drinking, shouting, singing, the objectifying of bodies amongst other forms of excess) created a feeling of independence and self-determination: now this is our turn, now we finally enjoy some down-time ourselves, as on this self-designed party T-shirt:

|

|

|

Image 8: T-shirts with a message that announces female transgression “I’ll be off then” (photo JT) |

<35>

Furthermore, the moment of a spontaneous decision to have sex with a stranger at the beach enabled one to feel power over one’s own experiences. At the same time the publicity offered safety in opposition to a hotel room, where the stranger could enforce himself upon one without the noticing and interference of others. Therefore, the uninhibited behavior of many female tourists was not regarded as promiscuity or even masculine and de-feminizing, but rather as a way to prove oneself of her liberty in the framework of a non-place. Yet, conceptualizing tourists in this context as being controlled by social rules that needed to be broken opens up other possibilities of control: in the ways participants were assigned roles and were led through the pilgrimage spaces, they were turned into containers of used-up consumer goods – T-shirts and carnivalesque pieces that may have never been worn outside the Ballermann, buckets for drinking, obscene objects that serve as souvenirs, fastfood with sexual connotations:

<36>

The pilgrimage’s offered freedom had to be actively appropriated, it did not come without the ritual equipment and without the transgression of former normatives. The usual experience had to be surpassed. The drinks had to be super-sized, the hangover to be super-hard, the songs to be sung extremely loud and the encounters to be especially intimate. Malle, des is schon was B’sonders! Wenn’d des net mitmachst, dann verstehst des a‘ net. Am A’fang is noch alles super toll, aber nach ein paar Dag, da willst net a mehr sauf’n!, a young man said at the beach after several days of partying in El Arenal – Mallorca is special, he says; you need to participate in order to understand it, even though it is, after several days, hard to take. At the end, he concluded, one doesn’t even wish to drink anymore. The need for over-exaggeration to ultimately succeed in the experience of the pilgrimage’s freedom was fulfilled in the massive consumption of all goods offered, until the body could not take it any longer. It was the experience of scripted unlimited consumption and guided going berserk that resulted in an equally scripted and guided sobering vomit and throwing away the objects of transgressive performance that was in the center of discourse. What stayed in Mallorca was not only the public secret of one’s transgressions, but also the ever retold tales of excessive saturation, and both helped those who traveled there to quickly construct group identity concepts that provide a framework for an intended confusion, a safe adventure.

Confusion and the commodity fetish

<37>

Our research trips to the Ballermann were contradictory pilgrimages to a homeless home: like everybody else, we felt caught in roles that yet promised liberation – from everyday life, the norms we had been disciplined into, and the fears of unveiling. During our immersions into our pilgrimage site, the Ballermann, it seemed, required a very different form of scholarly reflexivity from us, namely the ability to un-learn and un-be. It did not matter what we thought of our own role when we went to the beer halls trying to do research. Die Bushaltestelle ist draußen!, the bus stop is outside, is how a bar tender explained that we had to order drinks or leave. No longer being identifiable as researchers and experts, and not being in the environment to cite fitting scholarly articles and handbook chapters, we gave a strange sight, turning into mad scientists, confused researchers, and pilgrims. When we replied to other people’s questions about what we were doing at the Ballermann (stag party, birthday party, spring break party ...) that we were actually members of a German university trying to study communicative practices at the beach, we seemed to elicit reactions very similar to those such a reply is met with when one accidentally meets an acquaintance in front of a brothel: mild amusement and a raised eyebrow. This was an experience of multiple displacement – as social personae, as visitors to a foreign town, and as academics. And this is another contradictory side of it – even though our subsequent presentations and papers on the Ballermann usually were met with expressions of sympathy for the seemingly experienced abominations, our travels felt light, and delectable.

<38>

Perhaps, this was at the core of the untidy and noisy communication shared among the community at this disrupting place. There is, we think, something annihilating in the ways in which we engage with other people and things when we are out of place: practices of interaction with people whom we do not know, and with whom we may share just quick encounters, are practices that enhance the fleetingness of our relationships with others, and our lack of ability to engage with the places we meet them in. This fleetingness is described as one of the most salient aspects of encounters in tourism in Crispin Thurlow and Adam Jaworski’s work on the sociolinguistics of commodified mass mobilities (2010). Tourism, as one of the world’s largest industries of our time, they argue, produces fleetingness, as a norm and as an unquestioned experience. The unsettling, inappropriate in interactions is not unusual in tourism, but a repeated experience of tourists as well as their hosts.

<39>

Of course, there are various ways in which fleetingness and being out of place can play out. It makes a difference whether we decide to spend time in a yoga resort or at a beach where people come to party. Yet, all these homeless homes are always sites of enskillment, through the performances and architecture displayed there that serve as tools of communal learning of transgression. And even though these sites have been constructed, developed, expanded if not at all made for the tourists, as pilgrims searching rupture and confusion, those for whom all this is meant to exist will not be remembered after they have left their pilgrimage sites. These are places without graveyards in which people and memories might be laid to rest; there is no memorial site other than a virtual testimony or the front of a cheap T-shirt which lasts not longer than a summer.

<40>

Transgression at the non-place might unfold its particular unsettling power through the contradictions of experiences. Even though the package tour guarantees us to return, as we are only temporarily displaced, lost and confused, there is no firm ground here. The invented architecture of the Ballermann suggested Bavarian coziness and the anonymity of a department store at the same instance. The fleeting encounters we may have had took place within an utterly fundamental, absolutive framework: we needed to have them, in the form of yelled dialogue in the club or anonymous sex at the beach, unless we considered our stay a failure. Transgression was everything, and even though it was perhaps liberating, its ubiquity was utterly authoritative. At this homeless home, we were obliged to consume what we didn’t wish to elsewhere, as a form of sacrifice that gave healing because it provided us with stories that we could tell.

<41>

According to Mariela Silvana Vargas (2019), Walter Benjamin again describes modern capitalism as a crisis in his time, whose symptom is an experience of human isolation amongst others. The work force of people was assigned into one-handgrip jobs. Thus, the individual became more and more similar to a machine, despite the already ongoing industrialization. The abundance of information through new media like film and photography led in his view to a flood of information that was clouding the senses. Meanwhile, the newly produced goods were at the core of the definition of well-being. The encountering of other people did not take place by asking about one’s present condition anymore, but rather by asking about the price of one’s properties. According to Vargas, Benjamin described capitalism as a critical event which led to the loss of human intellect.

<42>

Although it is questionable whether this kind of crisis did take place for the first time when Benjamin was alive and whether humanity really disposed of its intelligence by then, the named symptoms of a crisis caused by capitalism do seem appropriate for the understanding of the Ballermann. The community that was suggested for the tourists was at all times only possible because it was carried by the parallel separation of and distancing from local residents, table dancers, street vendors, sex workers and probably all other tourist workers. The numerous postings online about the acting of the fools were regarded as accomplishments of a digitalized Ballermann culture and therefore the testimony over one’s own state of emergency was celebrated. Eventually, even the regular followers of the zone saw the only meaningful leftover in the cheapness of the holiday itself (see quoted comment above). According to that, the Ballermann in its known condition can be understood as a capitalist crisis par excellence.

<43>

Vargas describes a further nuance of Benjamin’s notion of the crisis as a situation of unalterability: the society has missed the point of time in which a meaningful change could have been made and is now deemed to stagnation. In relation to the Ballermann, ironically this aspect of the crisis seemed to have been abolished by another crisis again – the corona pandemic. Although for years local authorities had tried to prohibit the excesses of the tourist party zones, they had never succeeded. Only by the means of the corona crisis since 2020 the Ballermann was drastically changed and came to a pause as, of course, without visitors its only chance for survival was digital and in the tales that would be told about it. But since the act of transgression does serve to the reinstalment of state order as described above, and exactly this was what had been lost in the eyes of many people during the corona pandemic, it is not surprising that the symptoms of the Ballermann crisis condition had to be induced urgently again. From this perspective, the production of transgressive T-shirts with local reference even outside of Mallorca and its marketing on the internet for the locked in tourists at home was somehow a necessary condition for the upholding of the contradictory but mutually depending relationship between transgression and state order.

<44>

To W.G. Sebald, the contradictory annihilation of permanence that goes along with a temporary remaking of ourselves is not simply a feature of the tourist homeless homes, but a crucial experience of contemporary non-places that pervade urban spaces. Writing on a small graveyard in the island of Corsica, he asks about those places where people nowadays live – agglomerations we travel into and that are sites of our own replaceability rather than permanence (Sebald 2013: 37):

In den Stadtlandschaften des ausgehenden zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts hingegen, in denen jeder, von einer Stunde zur andern, ersetzbar und eigentlich bereits von Geburt an überzählig ist, kommt es darauf an, dauernd Ballast über Bord zu werfen, alles, woran man sich erinnern könnte, die Jugend, die Kindheit, die Herkunft, die Vorväter und Ahnen restlos zu vergessen.

In the urban landscapes of the late twentieth century in turn, where everybody, from one hour to the next, is replaceable and actually redundant right from his or her birth onwards, it is crucial throw away dead weight, and to finally forget everything that one might remember – youth, childhood, origin, forefathers and ancestors.

After all, those tales of adventure that emanate out of the quick encounters at the party zone provide the non-place with meaning and turn it into a home, for this year’s summer holiday, or a brief carnival foray. Healing from the bleakness of everyday life that Sebald, Augé and Ruf in different ways refer to takes place through the creation of places that allow for disruption and displacement. Quick encounters and the participation in fluid and feeble communities of practice therefore are not weird or forbidding, but are ubiquitous therapeutic and liberating experiences.

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to Ahmed C., Festus Badaseraye and numerous anonymous conversation partners, for sharing their many insights with us, as well as to our colleagues Fatou Cissé Kane, Angi Mietzner, Nico Nassenstein and Chris Bongartz for many inspiring discussions over the years. We remain indebted to two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions on an earlier draft of this paper. All mistakes are our own.

References

Andrews, Hazel 2009

'“Tits out for the boys and no back chat” – Gendered space on holiday.' Space and Culture 12,2:166-182.

Andrews, Hazel, Les Roberts & Tom Selwyn 2007

'Hospitality and eroticism.' International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research 1,3:247-262.

Andrews, Hazel 2014

'The enchantment of violence: tales from the Balearics.' In H. Andrews (ed.), Tourism and Violence, pp.49-68. Abingdon – New York: Routledge.

Augé, Marc 1992

Non-lieux. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Benjamin, Walter 2003 [1940]

'On the concept of history.' In Selected Writings 4, pp.389-400. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Brunotte, Ulrike 2004

Zwischen Eros und Krieg. Männerbund und Ritual in der Moderne. Berlin: Wagenbach.

Deumert, A. 2015

Wild and noisy publics: the continuation of politics by other means. Paper presented at University of Hamburg.

Farley, Paul & Michael Symmons Roberts 2011

Edgelands. London: Vintage.

Gosden, Chris & Yvonne Marshall 1999

'The cultural biography of objects.' World Archaeology 31,2:169-178.

Kuipers, Joel C. 2007

'Comments on ritual unintelligibility.' Text & Talk 27,4:559-566.

Ladwig, Patrice & Ricardo Roque 2018

‘Introduction: Mimetic Governmentality, Colonialism, and the State.’ Social Analysis 62,2:1-27.

Mietzner, Angelika 2017

'Mein Ballermann – Eine hervorragende Fernbeziehung.' The Mouth 2:33-45. https://themouthjournal.com/issue-no-2/ (accessed 02.05.2021)

Nassenstein, Nico & Anne Storch forthcoming

'Balamane. Variations on a noisy ground.' In I. H. Warnke & E. Erbe (eds.), Macht im Widerspruch. Heidelberg: Springer.

O‘Neill, Meggie & Brian Roberts. 2020

Walking Methods. Research on the Move. London & New York: Routledge.

Roberts, Les 2016

'Inhabiting the Edge: Tricksterism and Radical Liminality.' The Double Negative. http://www.thedoublenegative.co.uk/2016/02/inhabiting-the-edge-tricksterism-and-radical-liminality/ (01.05.2021)

Ruf, Frederick J. 2007

Bewildered Travel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Sebald, W.G. 2013

Campo Santo. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer.

Shepherd, Nick 2013

‘Archaeology in the Postcolony: Disciplinary entrapments, subaltern epistemologies.’ In P. Graves-Brown, R. Harrison & A. Piccini (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Contemporary World, pp.425-436. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Storch, Anne 2011

Secret Manipulations. New York: Oxford University Press.

Storch, Anne 2017

'Small Stories.' The Mouth 2:98-117, https://themouthjournal.com/issue-no-2/ (accessed 02.05.2021)

Storch, Anne & Nico Nassenstein 2020

'Café Senegales.' The Mouth 7:130-155, https://themouthjournal.com/issue-no-7 / (accessed 02.05.2021)

Thurlow, Crispin & Adam Jaworski 2010

Tourism Discourse: The Language of Global Mobility. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Traber, Janine 2017

'Der Verkauf von Verkehr.' The Mouth 2:59-77, https://themouthjournal.com/issue-no-2/ (accessed 02.05.2021)

Traber, Janine 2020

'The sexy banana – artifacts of gendered language in tourism.' In N. Nassenstein & A. Storch (eds.), Swearing and Cursing – Contexts and Practices in a Critical Perspective, pp. 259-280. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Taussig, Michael 1992

The Nervous System. New York: Routledge.

Taussig, Michael 1999

Defacement. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Vargas, Mariela Silvana 2019

Der Begriff der Krise bei Walter Benjamin und seine Relevanz heute. Radiofabrik Salzburg, Podcast, 14.02.2019. https://cba.fro.at/396148 (accessed 02.05.2021)

Voegelin, Salomé 2010

Listening to Noise and Silence. New York: Continuum.

Wöhler, Karlheinz 2011

Touristifizierung von Räumen. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Wood, Elizabeth Anne 2000

'Working in the fantasy factory. The attention hypothesis and the enacting of masculine power in strip clubs.' Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 29,1:5-31.

Wosick-Correa, Kassia R. & Lauren J. Joseph 2008

'Sexy ladies sexing ladies: Women as consumers in strip clubs.' Journal of Sex Research 45,3:201-216.

[1] The captain’s hat first became a popular item in El Arenal when it was offered as a souvenir referring to a locally played party hit (Bierkapitän ‘beer captain’) in 2018.

[2] https://www.spreadshirt.de/shop/design/sommerurlaub+2020+zuhause+maenner+bio+t-shirt+mit+v-ausschnitt-D5ebd51295fd3e47c0d1c407a?sellable=bBGlbBqXRXhrnEEZRzVy-686-12

[3] https://www.spreadshirt.de/shop/design/ausnahmezustand+party+club+maenner+t-shirt-D5d80f7e5b264a16d3e96ce48?sellable=lzdDnXnp7NUQ0AADz5b1-6-7

[4] https://www.spreadshirt.de/shop/design/corona+egal+frauen+t-shirt-D5eba82d05fd3e47c0d6f851b?sellable=VRejQkgzD3tl2rrQXe5D-631-8

[5] Referring to the debate on the name and emblem of Uncle Ben’s Rice with its racist semiotics, as well as declaring the utopia of a non-racist society – a motif saliently emerging during the state of emergency – as being bankrupt; equally, the label of the German company marketing the garment as ‘organic’ destroys the utopia of sustainable climate politics, as such T-shirts are meant to be garbage, worn just a few times before being dumped. https://www.spreadshirt.de/shop/design/mallorca+helmut+unisex+t-shirt+meliert-D5cf97c39b264a1640b73c516?sellable=ekQ5QOAaqduwBJr1Naz9-1212-8

[6] https://www.spreadshirt.de/shop/design/originale+helmut+frauen+t-shirt+mit+gerollten+aermeln-D5e7a47aa222509280cd3b176?sellable=xr0MJqw5zAIAeO904ov4-943-8

[7] https://www.spreadshirt.de/shop/design/helmut+mallorca+spruch+2020+t-shirt+frauen+t-shirt-D5e1b3e745fd3e45425c4f305?sellable=zrabBM7Dr8I3GGEb5MM1-631-8

[8] A chronicle of the absence of travel is provided in http://chris-bongartz.squarespace.com/coronatimes

[9] See e.g. Storch & Nassenstein (2020).

[10] The artist has explained this in various interviews: “Andreas Gabalier erzählt, was dahintersteckt und verrät auch, dass er es selbst gar nicht so genau weiß. ‘Ein Mädchen hat mir vor langer Zeit einmal ‘Hulapalu’ ins Ohr gesagt und gemeint ‘So schnell geht das nicht mit dem Hulapalu’. Anständig bin ich wieder nach Hause gefahren und hab mir gedacht ‘Was ist Hulapalu?’ und weiß es bis heute nicht’, lacht er. Vielleicht hat er ja Glück und irgendwer kann das große Rätsel auflösen.” ‘Andreas Gabalier explains the background and reveals not to be sure himself. ‘A long time ago, a girl whispered ‘Hulapalu’ into my ear and said ‘The Hulapalu does not work out that quickly’. In a modest manner, I went home and wondered ‘What is Hulapalu?’ and neither do I know nowadays.’, he laughes. Maybe he will be lucky and someone can resolve the big riddle.’ ( http://www.oe24.at/musik/schlager/Gabalier-So-irre-war-der-Videodreh/203823033 ; our translation)

[11] A critical comment is found in https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jul/05/mamading-magaluf-alcohol-sex-exploitation .

Lizenz

Empfohlene Zitierweise ¶

Storch A, Traber J (2021). Obsessive encounters. Afrikanistik Aegyptologie Online, Vol. 2021. (urn:nbn:de:0009-10-52683)

Bitte geben Sie beim Zitieren dieses Artikels die exakte URL und das Datum Ihres letzten Besuchs bei dieser Online-Adresse an.

Kommentare ¶

Es liegen noch keine Kommentare vor.

Möchten Sie Stellung zu diesem Artikel nehmen oder haben Sie Ergänzungen?

Kommentar einreichen.