Conditional-relatives in Senufo (Gur) and Manding (Mande): The encoding of generalizing relative clauses in West African languages [1]

urn:nbn:de:0009-10-50070

Abstract

Different West African languages of the Gur and Mande families have a type of relative clauses additionally marked as conditionals. They function as generalizing relatives and occur often in proverbs. The paper proposes an analysis of these constructions in the Senufo languages Syer ((or Western Karaboro, Burkina Faso) and Supyire (Mali) and in the Manding variety Bambara (Mali). It discusses for each language first the formal aspects of the most typical relative clauses modifying a definite referent, then those of hypothetical and course of events conditionals. This aims at showing the cumulative marking of both the relative and the conditional in the third type, the conditional-relative clauses. In the last section I give an account of the generalizing function of the conditional-relatives arguing that the cumulation of formal means reflects the cumulation of functions. Thus, the encoding of an event in a conditional clause marks it as hypothetical, removing from it any property characteristic of a concrete instance of the event type. This abstraction from a concrete instance is most evident in course of event conditionals, which show a factual ‘whenever’ relationship between the event in the conditional clause and that in the main clause. A relative clause has the function to modify and restrict clausally the referent of a type of entity. The generalizing function of a conditional-relative clause is brought about by the fact that the restricting event is hypothetical and hence abstracted from a real event.

Résumé

Plusieurs langues ouest africaines appartenant aux familles gur (voltaïque) et mandé possèdent un type de proposition relative en plus marquée comme conditionnelle. Elles fonctionnent comme relatives généralisantes et apparaissent souvent dans les proverbes. Cette contribution propose une analyse de ces constructions dans deux langues senufo: 1) en syer Karaboro de l’ouest, parlé au Burkina Faso, et 2) en supyire, parlé au Mali, ainsi que dans une langue mande, à savoir le parler bambara du Mali. Pour chaque langue je décris d’abord les aspects formels des propositions relatives modifiant un référent défini, ensuite celles des conditionnelles hypothétiques et des conditionnelles exprimant le cours des événements. L’objectif est de démontrer que les conditionnelles-relatives cumulent le marquage des relatives et des conditionnelles. La dernière section est destinée à la discussion de la fonction généralisante des conditionnelles-relatives. Je conclus que la cumulation des fonctions correspond à la cumulation des moyens formels. Ainsi, l’encodage d’un événement dans une conditionnelle le caractérise comme hypothétique, supprimant les propriétés caractéristiques d’un événement concret. Cette abstraction du concret est le mieux représentée dans les conditionnelles de cours d’événement, qui montrent elles-mêmes une relation généralisante factuelle entre l’évènement exprimé dans la conditionnelle et celui exprimé dans la proposition principale. Une proposition relative a la fonction de modifier et de limiter le référent d’une entité. La fonction généralisante des conditionnelles-relatives résulte du fait que l’évènement limitant le référent est hypothétique et donc abstrait d’un évènement réel.

Résumé

Résumé (Bambara)

Kúmasen sógolonnen súguya dɔ́ bɛ́ sɔ̀rɔ fàrafinna tìlebinyanfan kánw ná, mîn kúmasenbolo fɔ́lɔ yé kúmasenbolo mànkutulama yé ; à yé kúmasenbolo sáratilama yé fána. à bɛ́ báara kɛ́ í n’à fɔ́ kúmasenbolo mànkutulama mîn bɛ́ fɛ́nw bákurubafɔ. kúmasen nìnnu bɛ́ yé ntàlenw ná. nìn báara ìn bɛ́ jàteminɛ kófɔ, mîn bɛ́ hákilijakabɔ kɛ́ nìn fɔ́cogow lá kán sàba dè lá : 1) syɛ̀rkan (ní ò yé tìlebin Karaborokan yé), mîn bɛ́ fɔ́ Burukina, 2) sùpyirekan, mîn bɛ́ fɔ́ Mali lá ; òlu fìla bɛ́ɛ yé sɛ́nɛfɔkanw yé, àni bámanankan, ní ò yé màndenkan dɔ́ yé. ń yé kán kélen kélen bɛ́ɛ tà fɔ́lɔ, kà kúmasenbolo kɛ́rɛnkɛrɛnnen sífɔ : kúmasenbolo mànkutulama mínnu bɛ́ tɔ́gɔ mànkutu kà dàn sìgi ò lá, àni kúmasenbolo sáratilama mínnu bɛ́ làhalaya sínsinnenw fɔ́, àni làhalaya mínnu bɛ́ ków táabolo kófɔ. báara ìn ká láɲini yé k’à jìra kó kúmasenbolo tàamasiyɛn fìla fàralen bɛ́ kúmasenbolo kélen kɔ́nɔ. í n’à fɔ́ bámanankan ná, ní (wálima mána) àni mîn màbɛnnidaɲɛw bɛ́ yé kúmasenbolo kélen ìn kɔ́nɔ. báara ìn bɛ́ kùncɛ ní kɔ́rɔfɔ yé, mîn bɛ́ ɲɛ́sin kúmasen sógolonnen ìn táabolo mà, ní ò yé kà tɔ́gɔ mànkutu bákurubafɔ. kúma kùncɛ lá, ń b’à fɔ́ kó táabolow fàraɲɔgɔnkan àni nàsira kɛ́rɛnkɛrɛnnenw fàraɲɔgɔnkan bɛ́ tàli kɛ́ ɲɔ́gɔn ná [2].

[2] I am much indebted to Salabary Doumbia and Valentin Vydrin for their help in writing this Bambara summary. While basic vocabulary for grammar lessons in primary schools is available thanks to the cooperative work by Diallo et al. (2006), many terms (e.g. relative clause, conditional clause) have not been established yet in Bambara. Therefore, I take up Valentin Vydrin’s suggestions for these terms hoping to provoke the necessary discussion.

<1>

A number of West African languages have a type of relative clauses that show properties of both a relative and a conditional clause and that suggest a generalizing interpretation. The paper proposes a study of these so called conditional-relative clauses (CRCs) in the Gur languages Syer (officially called Western Karaboro)and Supyire and the Mande language Bambara. All of them have the obvious double marking in common, although the formal means used in the individual languages to mark relative and conditional clauses differ respectively. Simple relative clauses for instance differ with respect to the origin of the device marking a NP as relativized and with respect to the degree of subordination, some showing a hypotactic, others a more paratactic construction. What is common to the relative clauses in general in all discussed languages is the relation between the relative clause and the main clause in the resulting complex sentences: all the three languages are of the correlative type of relative clauses characterized by the presence of a NP that is anaphorically related to it in the main clause. The conditional clauses differ with respect to their characteristic marking. The Senufo languages use principally an auxiliary, whereas Bambara has the choice between a conjunction introducing the conditional clause and a conditional auxiliary.

<2>

The aim of this paper is to shed more light on this type of construction in the northeastern Senufo language Syer (Burkina Faso), for it has not been included in the recent grammar of this language (Dombrowsky-Hahn 2015). Further, showing that equivalent constructions exist in languages of the same region, even crosscutting language families, I provide evidence that the combination of features of relative and of conditional clauses to express a generalized clausal restriction of event participants is an areal phenomenon in West Africa. It seems to be a preferred strategy for generalizing relatives in languages which do not use representative-instance quantifiers equivalent to English any X, anything, anyone or whatever, whoever, etc. in this function.

I propose to study the structure of the conditional-relative as a special type of relative clauses by taking the form of each of the typical clauses it is based on as a starting point – the relative and the conditional. Subsequently the conditional-relative is presented. Assuming that similarities in form parallel those in function, this is followed by a discussion of the functions of the different constructions.

<3>

The paper is structured as follows. A section is consecrated to a language or dialect cluster respectively: Syer, Supyire, Bambara. Every section contains respectively a short typological introduction (resuming the larger group of Senufo); a presentation of the most typical relative clause, which is the RC modifying a definite NP, then a description of the hypothetical (and realis) conditional clause and finally, the conditional-relative clause. In a concluding section I try to explain how the linguistic means occurring in the CRC bring about the generalizing interpretation of this type of relative clause.

<4>

The analysis of the concerned sentences in the northeastern Senufo language Syer is based on data collected by myself during several research stays in the village of Ténguéréla between 2007 and 2012 [3]. For the other languages I cite published or submitted data and analyses. Thus, I refer to Carlson (1994, 1997) on Supyire (northwestern Senufo; Mali,), to Dumestre (2003) and Vydrin (2019) on Bambara (Manding; Mande; Mali). However, the construction is also attested in other, related languages, as found in Creissels & Sambou (2013) on Mandinka (Manding; Gambia, Senegal) and Creissels (2009a, 2009b) on Malinké of Kita (Manding; Mali).

|

|

|

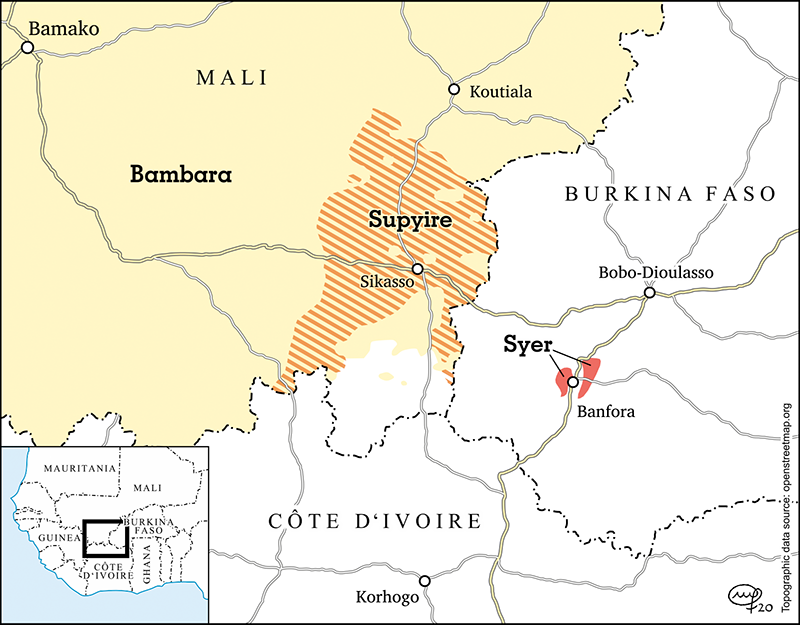

Map 1: Situation of Bambara, Supyire and Syer in Mali and Burkina Faso |

<5>

In Senufo languages, syntactic relations are determined by word order, which is S (Aux) (O) V (X). X stands for obliques and peripheral participants, most frequently marked by means of adpositions. Most adpositions are postpositions as in (1), but there are also prepositions some of which are combined to a postposition respectively, resulting in a kind of extended exponent [4].

|

Syer. Word order determined by linear sequencing. |

||||||

|

cɔ |

ní |

gbã̀n |

cùru |

la |

kĩ̀ |

|

|

woman |

rem |

pot5 |

wash |

1sgns |

pp |

|

|

S |

Aux |

O |

V |

X |

||

|

‘The woman washed the pot for me’. |

||||||

TAM values are encoded in three ways: first, one of two distinct verb forms - a perfective or an imperfective one - the latter of which is derived from the former; second, an auxiliary, and third, serial verb constructions (Carlson 1994, chap. 9). Several auxiliaries can be combined to a more complex tense-aspect value. In Syer, an auxiliary is not always present; instead, the tone on the subject pronoun and the tonal shape of the verb are decisive of some TAM values. For instance, the subject pronoun is L for the remote past, so that when the subject cɔ ‘woman’ in (1) is substituted with the corresponding pronoun, this pronoun gets a L tone: ù ní gbã̀n cùru la kĩ̀ ‘she washed the pot for me’. In spite of the importance of the subject pronoun as tone bearing element, only some TAM values require the resumption of the nominal subject with a pronoun (2).

|

Syer. Word order determined by linear sequencing. |

||||||

|

cɔ |

wú |

nàà |

lí |

cùru᷅-n |

||

|

woman |

pr1 |

prog |

pr5 |

wash-ipfv |

||

|

‘The woman used to wash / washes it regularly’. |

||||||

<6>

Clauses can have a verbal or a nonverbal predicate. The latter is a locative phrase, a nominal (3) or an ideophone. In the abbreviations in the text excerpts the subject and the predicate of clauses with nonverbal predicates are subsumed under the cover term copula subject (cs) and copula complement (cc); the linking element is glossed cop.

|

Syer. Clause with a nonverbal predicate. |

||||

|

[la ! |

ninlɔ]cs |

mɛ́ |

[wɔ̀dě-fwɔ̀]CC |

|

|

1sgns |

uncle |

cop |

money-owner |

|

|

‘My uncle is a rich man.’ |

||||

Senufo languages have an elaborated gender system. Carlson (2012) reconstructs eight noun classes for proto-Senufo; the actual languages show between six and nine noun classes forming three to six genders according to the particular language. For instance Supyire (North-west Senufo) has eight noun classes (Carlson 1994, chap. 3); the Nyɛnɛrɛ variety of Tyebari (Central Senufo) has seven (Rongier 2002), Kar (North-east Senufo) has six, while Syer (North-east Senufo) has nine, showing a supplementary class which is semantically associated with trees and bushes (cf. Dombrowsky-Hahn 2015, chap. 4).

|

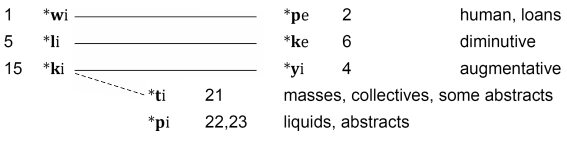

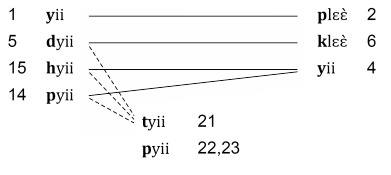

Reconstructed proto-Senufo noun class system (using reconstructed pronouns to represent classes) (Carlson 2012) |

|

|

|

<7>

Schema 4 shows the proto-Senufo system reconstructed by Carlson (2012). The numbers in this schema and in the glosses in this paper correspond to those used in Miehe et al. (2007) and Miehe et al. (2012) for the comparison of inflectional classes of nouns across Gur languages. The lines represent the linking of a singular with the corresponding plural class; classes *ti and *pi represent mass nouns, collectives, abstracts and liquids which do not usually partake in singular-plural pairings; the broken line stands for a supplementary association of some singular nouns of class *ki with the number value ‘collective’ as a special plural. Noun suffixes, pronouns and determiners which agree with the respective nouns bear a consonant characteristic for the respective noun class (in bold in tables 4 and 5) or a consonant closely related to it.

|

(5) |

Syer. Illustration of the agreement targets (interrogative/relative pronouns and determiners) |

|

|

The languages belonging to the Senufo branch of the Gur language family share a lexical basis and many grammatical features. Nevertheless, they differ with respect to other peculiarities of the grammar. For instance, with regard to the noun phrase, there is an important difference in the marking of definiteness. In Supyire it is encoded by means of definite suffixes that replace the basic nominal suffixes, however showing traces of the latter; in Syer definiteness is signalled (optionally) by articles preceding the nouns [5]. Similarly, the conditional-relative dealt with in this paper and the clause types it is based on show important differences in detail, justifying a separate account of the constructions in Supyire and in Syer.

<8>

Syer is a language spoken by about 25.000 speakers in southwestern Burkina Faso, in and around the town of Banfora. Known under the official name of Karaboro, it has several endonyms which reflect the name of the people who speak it and the place of settlement of these people. The data presented here have been recorded in tɛ̃́ɛ̃̀kùlu ‘Ténguéréla’, where the variety tɛ̃́ɛ̃̀ɲɛ̀r is spoken by the tɛ̃́ɛ̃̀ɲɛ̃᷅ɛ̃̀m [6]. Other speakers prefer however for the language the superordinate term ʃyɛ̃̀r, of which tɛ̃́ɛ̃̀ɲɛ̀r is the most conservative variety. Syer is also known as Western Karaboro, which is part of the Karaboro subbranch of Senufo. A recent grammar of Syer (Dombrowsky-Hahn 2015) has not taken into account complex constructions, but Dombrowsky-Hahn (2018) describes the main types of relative clauses attested in the language. The description in the following section confines to the most typical relative clauses (RCs), the conditional clauses and the CRCs showing the cumulated properties of the two other constructions.

<9>

A RC modifies or restricts the referent of a nominal constituent of another clause, the so called main clause (MC). Usually, only the MC is apt to figure as a simple independent clause, whereas the aptitude of a RC to occur as a simple clause depends on the degree of subordination of the RC, a point that will be addressed below. Only restrictive RCs are attested in Senufo languages.

The most frequently occurring RCs in Syer modify or restrict identifiable referents. The RC precedes the main clause (MC) and contains the head it modifies or a pronoun substituting a head. The RC does not directly assume a syntactic function in the MC which is rather indicated in it by means of a NP co-referentially related with the RC.

|

(6) |

Syer. Typical RC modifying an object; rel. determiner suffixed to nominal root |

|||||||

|

[[nã̀-tyìí]O |

pì |

ni |

nàà |

Ø |

m-pyi᷆-n]RC, |

|||

|

war-rel21 |

they |

rem |

prog |

ip-make-ipfv |

||||

|

‘The war they were engaged in, |

||||||||

|

[[tigè |

nda], |

[ti]GEN |

ju |

ni |

m-bugɔ̀]MC |

|||

|

d.dem21 |

deic.iden21 |

pr21 |

head |

rem |

ip-be.big |

|||

|

that’s it, its motives (its head) were important.’ |

||||||||

<10>

In the RC in (6), the relative morpheme -tyìí is suffixed to nã̂-, the stem of the head nã̂n ‘war’ with which it agrees in gender and number, exempt from the nominal suffix -n. The Syer relative morphemes are equivalent to the interrogative morphemes ‘which’ as illustrated in the question (7) [7]. The complete paradigm is given in (5) above.

|

(7) |

Syer. Interrogative clause; interrogative morpheme suffixed to the nominal root |

|||||||

|

|

nã̀-tyìi |

ntĩ̀ |

pì |

ni |

nàà |

m-pyi᷆-n? |

|

|

|

war-inter21 |

iden21 |

they |

rem |

prog |

ip-make-ipfv |

|||

|

‘Which war were they engaged in?’ |

||||||||

Both the relative and the interrogative morphemes occur in free or bound form. As a free morpheme, they follow a full noun (8a) or replace it (8c, 15); as bound morphemes, they are suffixed to a stem. For instance, in (8b), the interrogative / relative nominal suffix is attached immediately to the stem, the basic nominal suffix -l of the full noun wugel does not occur. For other examples of nouns and noun stems, see Dombrowsky-Hahn (2015, chapters 2 and 4, and 2018).

|

(8) |

Syer. Interrogative / relative morpheme as free and bound determiner, and as pronoun |

||

|

a) |

wugel dyii |

‘which hole; the hole that’ |

|

|

b) |

wuge-dyii |

‘which hole; the hole that’ |

|

|

c) |

dyii |

‘which one; the one that’ |

|

<11>

The uses of the interrogative determiner in its free and bound form is illustrated in (9), of it functioning as relative morpheme in (10), the free relative determiner further in the attested example (11), the bound one in (6). The distribution of the free and the bound forms are not entirely clear, but see Dombrowsky-Hahn (2018) for a hypothesis.

|

(9) |

Syer. Interrogative clause; bound and free forms of interrogative morpheme |

|||||||

|

ŋwùgɔ̀ |

Ø |

wùgɛ̀l |

wuge-dyii |

~ |

wugel |

dyii |

nì? |

|

|

snake15 |

prf |

hide |

hole-inter5 |

hole5 |

inter5 |

in |

||

|

‘In which hole has the snake hidden?’ |

||||||||

|

(10) |

Syer. Relative clause; bound and free forms of relative determiner |

||||||||||

|

[ŋwùgɔ̀ |

Ø |

wùgɛ̀l |

[wuge-dyii |

~ |

wugel |

dyii |

nì]OBL]RC, |

||||

|

snake15 |

prf |

hide |

hole-inter5 |

hole5 |

inter5 |

in |

|||||

|

‘The hole in which the snake has hidden, |

|||||||||||

|

[nɛ̃w |

mɛ́ |

[li |

nì]CC]MC |

||||||||

|

rat |

cop |

pr5 |

pp |

||||||||

|

there is a rat in it’ (Freely: ‘There is a rat in the hole in which the snake has hidden.’) |

|||||||||||

|

(11) |

Syer. Relative determiner (free form) in the RC |

|||||||||||

|

[[yí |

ŋwnɛ̃̀y |

ʃĩ̀ɲ |

yíí]o |

wù |

na |

Ø |

ŋgbɔ̃]RC, |

|||||

|

def4 |

stories4 |

two4 |

rel4 |

pr1 |

hest |

ip?-tell |

||||||

|

‘The two stories that she told yesterday, |

||||||||||||

|

[mɛ |

laa |

Ø |

tò |

lɛ̀ |

[yi |

nì]OBL]MC? |

||||||

|

2sg |

interior |

prf |

fall |

q |

pr4 |

pp |

||||||

|

do you remember them? (Secoke 0963 35:39) |

||||||||||||

<12>

Due to the strong association of some genders with semantic categories, for instance humans with gender 1/2, artifacts with gender 15 / 4 / 21, activities, problems, affairs or topics with gender 5/6 [8], the interrogative / relative morpheme is used as a pronoun when the type of entity can be inferred from the linguistic or extra-linguistic context. (12) illustrates the interrogative pronoun of class 5 referring to a topic, (13) the relative pronoun of class 2 referring to human beings.

|

(12) |

Syer. Interrogative pronoun (cl. 5) referring to a topic |

||||||

|

wo |

! mɛ |

kɛ |

yà |

nì |

dyii |

ǹ [9]? |

|

|

1pl |

fut |

go |

again |

with |

inter5 |

with |

|

|

‘With what do we continue (lit.: we will go on with which [topic])?’ (Secoke 0611 24:05) |

|||||||

|

(13) |

Syer. Relative pronoun (cl. 2) referring to human beings |

||||||||||

|

[[plɛɛ̀]S |

[pì]SRES |

ní |

n-lì |

ǹnɛ᷆ |

wò |

klu᷅ |

ǹ |

ǹnɛ᷆]RC |

|||

|

rel2 |

pr2 |

rem |

ip-go.out |

here |

1pl |

village |

in |

here |

|||

|

S |

Aux |

V |

X |

||||||||

|

‘Those who originated from our village here, |

|||||||||||

|

[pigè]S |

ní |

n-nìgɛ̀ |

... |

||||||||

|

d.dem2 |

rem |

ip-be.many |

|||||||||

|

they were many (Siwahii 0670 31:39,49) |

|||||||||||

<13>

There are two strategies available for the relativization of noun phrases in verbal clauses. In the first one, the in situ strategy, the constituents keep their unmarked order. It is the most frequent strategy attested for obliques (14), but is rather exceptional for objects.

|

Syer. In situ strategy, relativized oblique, suffixed relative determiner |

|||||||||

|

dɔ̃᷇g |

[ɲìgà |

ná |

bi |

kĩ̀ |

[nì |

yò-tyii |

nî,]OBL]RC |

||

|

so |

God |

hod |

them |

present |

with |

language-rel21 |

with |

||

|

S |

Aux |

O |

V |

Obl |

|||||

|

‘So, the language God presented them with, |

|||||||||

|

[[tigè |

ǹ]O |

bi |

m-pàr-ni]MC. |

||||||

|

d.dem21 |

iden21 |

they |

ip-talk-ipfv |

||||||

|

O |

S |

V |

|||||||

|

it is this one they speak > They speak the language that God gave them.’ (Madu 0643 22:44) |

|||||||||

<14>

The second one is the fronting strategy; it comprises the displacement of an object to clause-initial position, leaving a gap in its usual slot, indicated by Ø in the RC of (11). The fronting is a focusing mechanism that can be formulated as follows: S (Aux) O V -> O S (Aux) V. The extraction of the relativized object entails marking of the out-of-focus part of the clause as intransitive. This happens by means of an intransitive prefix, which is always present in intransitive clauses marked for certain TAM values (i.e. remote, hodiernal, hesternal past, general imperfective). (15) illustrates the in situ strategy of an interrogative clause, (16) the fronting strategy.

Fronting is one of several possible mechanisms to focus a constituent. A fronted constituent can be additionally marked with a simple or deictic identifier (7, 16). Alternatively, when a relativized item is fronted, the accompanying relative morpheme is marked with a H tone (11). Focusing is possible in situ as well, for instance by means of the focus marker wò in (15).

|

(15) |

Syer. Content question, interrogative pronoun in situ |

|||||

|

yè |

ni |

nàà |

dyii |

wò |

pyì-n? |

|

|

2pl |

rem |

prog |

inter5 |

dp |

do-ipfv |

|

|

S |

Aux |

O |

V |

|||

|

‘What were you doing?’ (Siwahii 0028a 00:42,6) |

||||||

|

(16) |

Syer. Content question, interrogative pronoun fronted |

||||||

|

dyii |

nì |

yè |

ni |

nàà |

Ø |

m-pyi᷆-n? |

|

|

inter5 |

iden5 |

2pl |

rem |

prog |

ip-do-ipfv |

||

|

O |

S |

Aux |

V |

||||

|

‘What were you doing?’ (elicited to Siwahii 0028a 00:42,6) |

|||||||

<15>

Fronting of obliques is possible, albeit rare. The fronting of an oblique does not involve preposition stranding nor pied piping in Syer. For subjects, only the fronting procedure is available. Since the subject is anyhow clause-initial in an unmarked clause it is not displaced. It is rather resumed by a simple pronoun which agrees with the head in gender and number. In (13), the simple pronoun pi of class 2 resumes the relative pronoun plɛɛ̀.

Constituents in clauses with nonverbal predicates cannot be fronted. For instance the locative predicate li nì in (10), designated as copula complement (CC) keeps its usual position following the copula [10].

<26>

Since the described RC in Syer corresponds to an independent simple interrogative clause, the entire complex sentence resembles a paratactic construction. Without a clear sign of subordination, the RC equivalent to a simple interrogative clause precedes the MC which equals an independent declarative clause [11]. In fact, the first clause can be qualified as RC only because of the relation that exists between it and a NP in the main clause that is coreferential with it, and because the whole functions as an intonational unit. Even if sometimes a very short suspensive pause can be perceived after the RC, there is neither an absolute pause, nor an utterance final lowering of pitch. These two features are present at the end of an independent clause.

<16>

In Comrie & Kuteva’s typology (2013b), a RC showing an element “which would not be present in the corresponding simple declarative sentence” equivalent to an interrogative pronoun is excluded from what they name the paratactic strategy. They reserve this category only to constructions in which RC and MC can function as independent declarative clauses. Within the authors’ typology based on relativizing strategies Syer RCs can rather be classified as a correlative RC. In this type, the RC modifies a NP that is a constituent in another clause (the MC), but it does not assume directly a syntactic role in it. Rather the MC contains an anaphoric NP that is coreferential with the RC and that indicates its syntactic role in the MC.

<17>

It is impossible to give an exhausting classification of conditional clauses for the languages discussed in the frame of the present contribution. Therefore, the description will be restricted to content conditionals [12], which are solely relevant for the conditional-relative constructions as the topic of this paper. The hypothetical conditionals (HC) and the course of events conditionals (CEC) are the most frequent content conditionals. They share the formal aspects in each language respectively. In this section the characteristics of Syer conditionals are presented.

|

(17) |

Syer. Hypothetical conditional |

|||||||

|

[ǹ |

mɛ |

jí]COND |

[gi |

! mɛ |

la |

gbu]MC |

||

|

1sgs |

cond |

enter |

pr15 |

fut |

1sgns |

kill |

||

|

‘If I enter, it (ref.: the thing in the water) will kill me.’ (Madu 048 18:15,3) |

||||||||

<18>

In a hypothetical conditional construction, the apodosis follows the protasis, sometimes separated from it by a suspensive pause. There is no conditional conjunction; conditional marking is rather achieved through the combination of a L tone on the pronominal subject (17) (other NPs maintain their respective tune, as in (21)), the conditional auxiliary mɛ (glossed cond) and a HL tune [13]. The distribution of the HL tune is determined by two factors, first the presence or absence of an object following the auxiliary, and second, the tonal class of the verb. In an intransitive clause, when no object separates the auxiliary from the verb, the auxiliary is realized M and the verb shows HL, except when the verb belongs to the class of L verbs. The L tone is maintained on these verbs, and the H of the HL auxiliary moves to the auxiliary on its left. The realization of the conditional in intransitive clauses for all three tonal classes of verbs is illustrated in (18).

|

(18) |

Syer, TAM and conditional marking for three tonal classes of verbs |

|||||||

|

tonal class of verb |

M |

HL |

L |

|||||

|

ji |

'enter' |

yírì |

'get up' |

tò |

‘fall’ |

|||

|

conditional |

ù mɛ jî |

‘if s/he enters’ |

ù mɛ yírì |

‘if s/he gets up’ |

ù mɛ́ tò |

‘if s/he falls’ |

||

The distinction between M and HL verb classes is neutralized in the conditional, but in the L class of verbs, which is the most stable one, the verb maintains its L tone. When an oblique follows a verb of the M or the HL class, the verb is realized H instead of HL. For instance the verb klô, which is realized HL when it stands in utterance final position is realized H in nonfinal position in (19). Sometimes, the H realization is found also when the suspensive pause between the protasis and the apodosis is almost absent as in (17), stressing so the intonational unity of the complex sentence.

|

(19) |

Syer. Conditional: H realization when the verb (HL class) is not clause-final |

||||||||||

|

mɛ̀ |

mɛ |

kló |

nì |

la |

ni |

... |

|||||

|

2sg |

cond |

stay |

with |

1sgns |

with |

||||||

|

‘If you stay with me ...’ |

|||||||||||

<19>

In a transitive clause, when an object precedes the verb, the distribution is more complex. It depends on the tone of the object. For instance, with a nominal object bearing an initial L tone (sã̀sugu in (15)) the characteristic HL is reduced to H, associated to the auxiliary. The tonal realization of the verb then depends on the tone of the object NP (cp. Dombrowsky-Hahn 2015, chap. 3, section 3.5.3).

|

(20) |

Syer. Ambiguous interpretation: realis CEC and hypothetical HC |

|||||||||

|

mɛ̀ |

mɛ́ |

sã̀sugu |

wɛ̂r, |

mɛ |

! mɛ |

wɔ̂de᷅ |

ɲã̀ã̀. |

|||

|

2sg |

cond |

corn |

cultivate |

you |

fut |

money |

see |

|||

|

‘If you cultivate corn you (will) get money.’ ‘If one cultivates corn one gets money.’ (Misc 0270 2011.02.25) |

||||||||||

<20>

Content conditionals can be distinguished according to the speaker’s attitude towards the likelihood of the realization of the event, ranging from factual at the one end to counterfactual conditionals (in the past) at the other, passing through less likely or unlikely conditionals. HCs are potentially real or unreal, whereas CECs are considered to be real. (17) is an example of a hypothetical conditional, in which “the consequent is somehow predicted to follow from satisfying the ‘condition’ expressed in the antecedent” (Athanasiadou & Dirven 1997:62). In such cases a non-factual hypothetical situation is expressed in the antecedent and therefore also in the consequent.

In a course of events conditional two events co-occur, and the one is dependent on the other. They express a factual ‘whenever’ relationship. According to Athanasiadou & Dirven (1997:71 ff), the CEC and the HC differ with respect to the speaker’s commitment to the realization of the situation: in a CEC the speaker makes a commitment as to the actual, frequent or general realization of the two situations, whereas in the HC the speaker distances her-/himself from any commitment to real occurrence but considers potential realities. In both cases the conditional marking creates a hypothetical world, but CECs differ from HCs among others by the use of ‘higher-order entities’ (Langacker 1997), such as for instance ndye ‘person’ in (21). Tense-aspect categories in the main clause contribute to a factual interpretation, too. Thus, the imperfective in (21) is interpreted as a habitual and consequently the entire sentence describes a generally observed situation [14].

|

(21) |

Syer. Course of events (‘whenever’) conditional |

|||||||

|

ndye |

mɛ |

lé |

mɛ |

nã̀ã̀ni, |

||||

|

person |

cond |

stop |

you |

next.to |

||||

|

‘If someone comes to stand next to you, |

||||||||

|

ú |

si |

ŋ-klɛ̀-n |

u |

kɛ |

yà |

|||

|

s/he |

neg |

ip-look.for-ipfv |

s/he.subj |

go.away |

again |

|||

|

s/he doesn’t want to leave again’ (Misc 0093) |

||||||||

<21>

CRCs are constructions that cumulate relative and conditional marking. An example is the elicited sentence (22). The relative pronoun in the RC and the simple pronoun coreferential with it in the MC are the elements characterizing a relative, and the conditional auxiliary and the HL tune on the verb the conditional clause.

|

(22) |

Syer. CRC, relativized subject |

|||||

|

[[yii]S |

mɛ |

wɛ̂r]CRC, |

[[ú]S |

mɛ |

kĩ̀]MC |

|

|

rel1 |

cond |

cultivate |

pr1.hab |

you |

present |

|

|

‘‘Whoever / anyone who cultivates, offers you gifts’. |

||||||

Natural data from texts are usually more complex. Thus, in (23), the relative is separated from the main clause by the additional clause ‘the young is with her’. It expresses another condition, however without showing conditional marking.

|

(23) |

Syer. CRC, relativized subject, no following resumptive pronoun |

||||||||||

|

If you see a frightened fisherman fleeing in his boat, it is the following: |

|||||||||||

|

[[yii]S |

mɛ́ |

ʃyè]CRC |

plòge |

mɛ́ |

wu |

ye, |

[[wu]S |

||||

|

rel1 |

cond |

give.birth |

young |

cop |

pr1 |

with |

pr1 |

||||

|

‘Anyone (ref. hippo-mare) that has given birth (to a young), (if) the foal is with her, |

|||||||||||

|

yɛ́ |

wu |

nàà |

nã̂n |

pyì-n |

nì |

yê |

n᷅.]MC |

||||

|

defeat |

she.subj |

prog |

war |

make-ipfv |

with |

2pl |

with |

||||

|

(she) can start fighting with you.’ Freely: ‘A(ny) hippo-mare that has given birth can start fighting with you, |

|||||||||||

<22>

This type of clause shares two features with referential definite relatives: first, the marking with a relative morpheme (yii in (22) and (23)), which determines or replaces a head, signaling that the so modified or restricted NP is a constituent in a following main clause. Second, the presence of a NP in the MC that is coreferential with the RC and which indicates its syntactic function in the MC. Insofar, the CRC is a correlative construction like the RC. The CRC shares with the conditional clause its marking by means of the conditional auxiliary mɛ and the tune characteristic of the conditional [15] (cf. 2.2.2). This conditional marking makes the CRC an unequivocally subordinated clause, whereas the referential RC resembles an independent interrogative clause. While two strategies are possible in the referential definite RCs (at least for objects and obliques), only the in situ strategy is available in the CRCs (and in the conditional). No displacement of constituents is possible; accordingly the fronting strategy does not apply. That is, the subject in (22) and (23) cannot be resumed by a simple pronoun respectively, nor can the object in (24) be fronted.

|

(24) |

Syer. CRC, relativized object, canonical position before the verb [16] |

|||||||

|

[mɛ̀ |

mɛ́ |

[fàwɔ̀-yii]O |

ɲã̀ã̀ |

lùgɔ̀ |

la᷆ŋ]CRC |

[pi |

ŋwròm |

|

|

you |

cond |

dirt-rel1 |

see |

water |

in |

def22,23 |

waste22,23 |

|

|

S |

Aux |

O |

V |

S |

||||

|

‘Any dirt you may see in the water, it is the waste |

||||||||

|

pìgè |

mpĩ̀ |

pì |

káá |

pyì |

[ki |

ʃi᷆]CC]MC. |

||

|

d.dem22,23 |

iden22,23 |

pr22,23 |

it(go) |

be |

pr15 |

sort |

||

|

that became like this.’ (Madu 0619 21:43,9) |

||||||||

<23>

The examples in (25) through (27) illustrate a) a referential definite RC in the perfect aspect (Ø auxiliary), making use of the in situ strategy; b) same as a) but using the fronting strategy; c) a CRC and d) the unavailable fronting strategy within this type of relatives.

|

(25) |

Relativization of S; in situ and fronting strategies in RC + CRC; M tone verb |

|||

|

a) |

RC, S relativized, in situ impossible |

*yii wɛr |

‘the one who cultivated’ |

|

|

b) |

RC, S relativized, fronting |

yíí ù wɛr |

‘the one who cultivated’ |

|

|

c) |

CRC, S relativized |

yii mɛ wɛ̂r |

‘whoever cultivates’ |

|

|

d) |

CRC, S relativized, fronting impossible |

*yii ù mɛ wɛ̂r .... |

‘whoever cultivates’ |

|

|

(26) |

Relativization of S; in situ and fronting strategies in RC + CRC; L tone verb |

|||

|

a) |

RC, S relativized, in situ impossible |

*yii ʃyè |

‘the one who has given birth’ |

|

|

b) |

RC, S relativized, fronting |

yíí ù ʃyè |

‘the one who has given birth’ |

|

|

c) |

CRC, S relativized |

yii mɛ́ ʃyè |

‘anyone who has given birth’ |

|

|

d) |

CRC, S relativized, fronting impossible |

*yii ù mɛ́ ʃyè |

‘anyone who has given birth’ |

|

|

(27) |

Relativization of O; in situ and fronting strategies in RC + CRC |

|||

|

a) |

RC, O relativized, in situ |

mɛ̀ fàwɔ̀-yii ɲã̀ã̀ lùgɔ̀ la᷆ŋ |

‘the dirt you saw in the water’ |

|

|

b) |

RC, O relativized, fronting |

fàwɔ̀-yíí mɛ̀ ɲã̀ã̀ lùgɔ̀ la᷆ŋ |

‘the dirt you saw in the water’ |

|

|

c) |

CRC, O relativized |

mɛ̀ mɛ́ fàwɔ̀-yii ɲã̀ã̀ lùgɔ̀ la᷆ŋ |

‘any dirt you see in the water’ |

|

|

d) |

CRC, O relativized, fronting impossible |

*fàwɔ̀-yíí mɛ̀ mɛ́ ɲã̀ã̀ lùgɔ̀ la᷆ŋ |

‘any dirt you see in the water’ |

|

The CRC shares with both the relative and the conditional its intonational unity with the main clause, especially the absence of a final lowering and a suspensive pause at the frontier between the CRC and the MC.

<24>

In this section I have discussed three constructions: the RC, the conditional and the CRC, the last of which brings together the characteristic features of the two previous constructions.

The RC in Syer is a correlative construction; that is, the RC does not constitute directly a nominal constituent in the MC; it is rather represented in it by means of a coreferential NP. The relativized noun is marked or replaced by a relative morpheme which originates in the interrogative morpheme ‘which’ agreeing in gender and number with the antecedent. On a purely structural level, the complex sentence is a paratactic construction, for both the RC and the MC (exempt the characteristic intonation making them a coherent unit) can occur as independent interrogative and declarative clauses respectively. Nevertheless, in the current typology, the Syer RC is not considered to belong to the paratactic type which requires both the RC and the MC clauses to be apt to figure as independent declarative clauses. Two strategies are possible in typical RCs: the in situ and the fronting strategy. The latter serves to particularly focus on the relativized item

<25>

Syer conditionals are not introduced by a conjunction; they are marked by means of an auxiliary, which is a subordinator at the same time. Unable to figure as an independent clause, the conditional clause is unequivocally subordinated. Due to the presence of the conditional auxiliary, the CRC is subordinated, too. The CRC is, like the RC, a correlative construction. However, unlike RCs, CRCs only admit the in situ strategy.

<26>

Supyire is a language of the northwestern subgroup of Senufo, spoken in southern Mali. Minute information on Supyire relatives is found in Carlson’s (1994) grammar, and differences between relatives in the northeastern Senufo (to which Syer belongs) and northwestern Senufo are put together in Carlson (1997). The following discussion is based on these documents.

<27>

Closely related, the northwestern Senufo language Supyire and its northeastern relative Syer share many features, but they also show dissimilarities. Those concerning relative clauses will be discussed in the following. The commonalities are the order RC – MC and the choice between the in situ and the fronting strategies. The fronting strategy, which is more common, includes the resumption of a relativized subject by a simple pronoun (28) and the dislocation of a relativized object (29) to clause-initial position. Like in Syer, a gap is left in the object’s usual position (signaled as Ø in 29).

|

(28) |

Supyire. RC with relativized subject, fronting strategy, optional marking with dem |

||||||||||||

|

[yaagé [17] |

(ŋké)]S |

[k’]SRES |

a |

ù |

bò |

ké]RC |

|||||||

|

thing.def15 |

rel15 [18] |

pr15 |

prf |

pr1 |

kill |

rm |

|||||||

|

‘(Lit.: The thing that killed him, |

|||||||||||||

|

[mu |

a |

[kùrù] |

cé]MC |

||||||||||

|

you |

prf |

d.dem15 |

know |

||||||||||

|

‘you know it.) You know the thing that killed him.’ (Carlson 1997:32, ex. 25a.) |

|||||||||||||

|

(29) |

Supyire. RC with relativized object, fronting strategy |

|||||||

|

[[myàhíí]o |

u |

a |

Ø |

cèè |

gé]RC, |

|||

|

song.def6 |

pr1 |

prf |

sing |

rm |

||||

|

O |

S |

Aux |

V |

|||||

|

‘The songs which she sang, |

||||||||

|

[[ci]CS |

náhá |

mìì |

fúnŋí |

í]MC |

||||

|

pr6 |

be.here |

my |

inside |

in |

||||

|

they are here inside me.’ Freely: ‘I remember the songs which she sang.’ |

||||||||

<28>

Like in Syer, the MC in Supyire includes a NP coreferential with the RC (the discourse demonstrative kuru in (28) and in (30), the simple pronoun ci in (29)). Although both Syer and Supyire relatives belong to the correlative type in Kuteva & Comrie’s (2005) and Comrie & Kuteva’s (2013a, 2013b) typology, they differ with respect to the degree of subordination. As shown above, the typical Syer RC is part of a paratactic construction [19], whereas the Supyire RC bears traces of nominalization, and hence is in a more hypotactic relation to the MC (Carlson 1997:32). The sign of nominalization in Supyire RCs is the invariant clause-final particle ké. The form of this morpheme resembles the nominal suffix of nouns belonging to the singular class 15 (Carlson’s gender 2 singular), -gV and its definite counterpart -ge or -ke. This parallel between the clause-final marker and a nominal suffix is interpreted by Carlson as a sign of former nominalization and hence subordination of the RC. The nominalization hypothesis is corroborated by data from the central Senufo language Senari (Cebaara) where the corresponding clause-final morpheme is lè, showing the consonant l (cf. section 2.1) characteristic of the noun class 5 (Carlson’s gender 3 singular). The author therefore assumes that originally the final marker might have been variable, showing agreement with the head.

<29>

The nominalization of a clause is considered as the process by which a finite verbal clause is converted into a noun phrase. Usually, in the course of this process the verb becomes a head noun, the tense-aspect-modal morphology is lost, and subject or object acquires genitive case-marking, among others (Givón 2001:24). None of these adjustments is presently observable in Supyire (or Cebaara), considered by Givón (2001:29) to be an extreme finite (non-embedding) language. Nevertheless, the clause-final particle in Supyire relatives is never present in an independent clause and can be interpreted as a signal of subordination. Thus, the classification as correlative construction says nothing about the degree of subordination in the arrangement of the relative and main clauses, and both the paratactic construction in Syer and the more hypotactic construction in Supyire can be qualified as correlatives. That correlative relative clauses can be paratactic or hypotactic constructions has been shown also for different branches of Mande languages (Creissels 2009a, Nikitina 2012).

<30>

A major difference between Syer and Supyire is the marking of the head of a RC. While in Supyire the clause-final particle ké is obligatory in all RCs, the marking of the head NP as relativized is optional. This marking consists of a morpheme agreeing in gender and number with the head. In (28) its optional presence is indicated in brackets; in (29) the option is not indicated. The relative determiner corresponds to the deictic demonstrative; however, unlike the relative determiner, the demonstrative precedes the noun (i.e. ŋ̀ké yaagé ‘this thing’, but yaagé ŋké ‘the thing that’). In clauses with an unmentioned head, the same morphemes function as relative pronouns.

In the in situ version of the RC, the relative determiner is obligatory, and it is often extended by the suffix -mu. Like in the neighbor language Minyanka spoken in Mali (Dombrowsky-Hahn 1998), the form of this suffix concurrent with the maintenance of the canonical word order (or application of the in situ strategy) result from contact with Bambara, the lingua franca used in the region (Carlson 1997:33, and below). In Bambara, the word order is extremely strict, and in relative clauses the relative morpheme mîn [mĩ]~ mûn [mũ] (which is the source of the Supyire suffix -mu) follows the head or replaces it.

|

(30) |

Supyire. RC modifying an object, in situ strategy, |

||||||||

|

[ali |

níɲjáà |

jínàŋa |

à |

[yaagé |

ŋ̀ké-mù]O |

kàlìfǎ |

|||

|

even |

today |

jinn.def1 |

prf |

thing.def15 |

rel15-suf |

entrust |

|||

|

‘Even today the jinn which thing entrusted to him, it is there.’ |

|||||||||

|

ú |

ná |

ge]RC, |

[[kuru]CS |

na |

wá |

aní]MC |

|||

|

pr1 |

pp |

rm |

d.dem15 |

prog |

be.there |

there |

|||

|

Freely: ‘Even today the thing which the jinn entrusted to him is there’. (Carlson 1994:498-499) |

|||||||||

<31>

Content conditionals show the conditional auxiliary ká (or its allomorph ahá) in the protasis, and future tense in the apodosis. This is illustrated in (23).

|

(31) |

Supyire. Hypothetical conditional |

||||||||

|

[mu |

ahá |

mìì |

bó]COND, |

[mu |

tacwóŋi |

sí |

ŋ̀kwû]MC |

||

|

you |

cond |

me |

kill |

your |

fiancée.def1 |

fut |

fp-die |

||

|

‘If you kill me, your fiancée will die.’ (Carlson 1994:571, extract of ex. 55) |

|||||||||

<32>

Carlson (1994:507-509) deals with the conditional-relative clause in chapter 13 on relative clauses in a section entitled “conditional-relative clauses”, and, in chapter 15 on conditionals, he mentions them under the heading “other uses of the conditional” (1994:580). He notes that the “‘whoever’ meaning” is obtained by using the conditional auxiliary in a relative clause with a nonreferential relativized NP. (32) shows such a sentence with a relativized subject, (33) with a relativized object.

|

(32) |

Supyire. CRC, relativized subject |

|||||

|

[[nàŋi |

ŋ̀gé-mù]S |

ká |

ḿ-pá |

ge]CRC, |

||

|

man.def1 |

rel1-suf |

cond |

ip-come |

rm |

||

|

‘Whichever man comes, |

||||||

|

[wyɛ́rɛ́ŋi |

kan |

[ura |

à]OBL] MC |

|||

|

money.def1 |

give |

d.dem1 |

to |

|||

|

give him the money.’ (Carlson 1994:580) |

||||||

<33>

The account of the relative clauses on the one hand and of conditional clauses on the other hand shows that the conditional-relative clauses ((32) and (33)) combine features of the two previous constructions. They share the auxiliary with the conditional and the marking of the head NP by means of the demonstrative-relative determiner and the clause final relative marker ge with the relative. Furthermore, the main clause comprises a NP co-referentially related with the CRC (ura in (32) and (33)).

However, the CRC differs from the RC by the impossibility to dislocate the relativized item to the left; i.e. the fronting strategy does not apply with the CRC. Correspondingly, the relativized NP is always marked by means of the extended relative determiner rel+suf (Carlson 1994:507). The obligatory use of this determiner and the resemblance of this construction to similar sentences in Bambara (Manding, see below) suggest here again a certain influence of the lingua franca on the Senufo language. However, as shown in section 2.2, a very similar construction exists in Syer without any borrowed form. Syer seems generally to have undergone much less influence by the Dyula variety of the Manding cluster used as lingua franca in southwestern Burkina Faso, so that it is difficult to judge whether we are dealing with an instance of metatypy here as well, or whether it is a phenomenon of larger areal distribution.

|

(33) |

Supyire. CRC, relativized object |

|||||||

|

[u |

ahá |

[pyàŋi |

ŋ̀gé-mù]O |

tà |

ké]CRC |

|||

|

pr1 |

cond |

child.def1 |

rel1-suf |

get |

rm |

|||

|

‘She would get whatever child, |

||||||||

|

[[ura]S |

asì |

ǹ-tòrò]MC |

||||||

|

d.dem1 |

hab.seq |

ip-pass |

||||||

|

it would die.’ Freely: ‘Whatever child she got would die.’ (Carlson 1994:508) |

||||||||

<34>

RCs in Supyire are correlative constructions. Both strategies, the in situ and the fronting strategy are allowed in typical RCs. All RCs are obligatorily marked with the immutable clause-final marker ke or ge, which is interpreted as a trace of nominalization of the clause and which functions as subordinator. There is also a relative determiner marking a head as relativized and showing agreement with it. It follows the definite form of the head when used as determiner; the same form replaces the head when used as pronoun. The forms of the relative determiner correspond to deictic demonstratives, but their position with respect to the head differs, for the deictic demonstratives usually precede the head. Relative determiners are optional when the relativized item is fronted to the initial position of a RC. But when the in situ strategy is used, they are obligatory and, additionally, they show a suffix -mu added to the demonstrative element.

Conditional clauses are encoded by means of a conditional auxiliary. The same auxiliary is found in CRCs, which show at the same time features that characterize RCs. Allowing only the in situ strategy, relativized items in CRCs obligatorily bear the extended rel+suf marker.

<35>

Similar conditional-relative clauses have been described for Malinké of Kita (màningakan, southeastern Mali) by Creissels (2009a, 2009b), for Mandinka (mandinkakáŋo (Gambia, Senegal)) by Creissels & Sambou (2013), and recently for Bambara (bámanankan, Mali) by Vydrin (2019). All these are varieties of the Manding dialect cluster belonging to the family of Mande languages. Although a discussion of the constructions would be worthwhile for all three languages, the limited space allows me considering only one of them. Therefore, I restrict the following presentation to Bambara [20], focusing, after a short typological introduction, on typical relative clauses, typical conditionals and conditional-relative clauses.

<36>

Senufo and Mande languages share the word order S Aux (O) V (X). In Bambara, the auxiliary is a constitutive and obligatory part of an independent clause, which fuses a TAM value with either affirmative or negative polarity [21]. An exception is the perfective value in intransitive affirmative clauses for which the auxiliary is replaced by the inflectional morpheme -ra (or its allomorphs -la, -na) suffixed to the verb. This results in the schematic representation S V- ra for intransitive affirmative clauses in the perfective aspect. The difference can be seen comparing an intransitive affirmative clause in the imperfective (34) and in the perfective aspect (35).

In Bambara (and Manding in general), the verb does not show agreement with the subject or the object. Syntactic relations are determined by word order, which is much more strict than in Syer and Supyire (or Senufo in general). So, no dislocation of a constituent is possible in Bambara, for instance as a focusing strategy.

<37>

Next to clauses with verbal predicates, Manding varieties dispose of several types of clauses with nonverbal predicates.

|

(34) |

Bambara. Intransitive affirmative clause, imperfective aspect |

||||

|

dén |

bɛ́ |

kási |

|||

|

child |

ipfv.aff |

cry |

|||

|

S |

Aux |

V |

|||

|

‘The child is crying ~ cries.’ |

|||||

|

(35) |

Bambara. Intransitive affirmative clause, perfective aspect |

||||

|

dén |

kási-ra |

||||

|

child |

cry-pfv.aff |

||||

|

S |

V-ra |

||||

|

‘The child cried.’ |

|||||

<38>

A main difference vis-à-vis Senufo or Gur in general is the absence of a gender system in Mande. There is a unique nominal marker in Bambara, called the definite marker or definite modality by Dumestre (2003:137) and ‘definite’ article by Vydrin (2019:33), but ‘specific article’ in the Corpus bambara de référence [22]. It has the form of a floating Low tone (noted `) causing a downstep of a following H, except for a few words in which it is rather perceived as part of the tonal contour of the word. Among the few words there is the relative morpheme mîn (Vydrin 2019). No thorough study of the role of the article for the marking of referentiality and definiteness in Bambara being available up to now, the author only adds that it occurrs more frequently than the definite article in French, and refers to Creissels’ (2009b) description of Kita Malinke where its use is very similar to that in Bambara. In both varieties it is the absence of the article that is marked, not its presence. Resuming and interpreting the most important of Creissels’ findings, it is possible to say that the article is present in the citation form of nouns and other generic contexts (for instance objects in affirmative clauses), and with nouns that have a referential-definite and a referential indefinite [23] interpretation. It is absent with non-referential NPs among others in such negative clauses as mùso tɛ́ ‘This is not a woman’.

<39>

In Bambara, there is a unique plural morpheme -u (written in the orthography as -w, i.e. mùso ` ‘woman’; mùsoẁ ‘women’) suffixed to the lexeme. In a noun phrase, the plural morpheme is added to the last element, for instance in a NP comprising a noun + an attribute, such as for instance an adjective, the plural is suffixed to the adjective which follows the noun (mùso ɲùman` ‘a nice woman’; mùso ɲùmanẁ ‘nice women’).

The tonal article is associated to the plural suffix -u, resulting in [ù] (ẁ in the orthography) (as in mùso ɲùmanẁ ‘nice women’). There is also the more recently developed ‘definite’ article ìn [24] (40), originating in the deictic demonstrative nìn but whose distribution/function and delimitation vis-à-vis the tonal definite/specific article is not yet understood.

<40>

The typical relative clause in Bambara [25] precedes the MC. The relativized item is followed by the tonal article in form of a floating low and marked by the relative morpheme mîn [26]. As shown by Creissels (2009a:46), mîn originates from a demonstrative morpheme, whose demonstrative function got lost in Bambara but that has been maintained in Koyaga of Mankono (Ivory Coast), another Manding variety. In this variety it fulfills both the demonstrative and the relativizing functions. The same form is used as determiner and, when the head remains unmentioned, as pronoun. It varies only with respect to number, the plural being mínnù or múnnù. Like in Senufo, the RC and the MC constitute a correlative construction. This means that the MC shows a NP coreferential with the RC, frequently in form of the (discourse) demonstrative (d.dem) pronoun ò (36), or another pronoun, or the repetition of the head determined by the discourse demonstrative morpheme (37).

|

(36) |

Bambara. RC modifying an object; coreferential NP in MC = ò |

|||||||||

|

[à |

táa-ra |

[dén |

fàsa |

mîn]O |

fìli |

kúngɔ |

||||

|

3sg |

go-pfv.aff |

child |

emanciated |

rel |

discard |

wilderness |

||||

|

‘The emaciated child that she threw away in the wilderness, |

||||||||||

|

rɔ́]RC |

[jínɛ-w |

nà-na |

[ò]O |

tà]MC |

kà |

ò |

lámara |

|||

|

pp |

djinn-pl |

come-pfv.aff |

d.dem |

take |

inf |

d.dem |

raise |

|||

|

djinns came and took it and raised it.’ (Freely: Djinns came and took the emaciated child that she had thrown |

||||||||||

|

(37) |

Bambara. RC modifying an oblique; coreferential NP in MC = ò + repeated head |

|||||||||||

|

[npògotigi-w |

táa-ra |

[síra |

mîn |

fɛ̀]OBL]RC, |

||||||||

|

girl-pl |

go-pfv.aff |

way |

rel |

pp |

||||||||

|

‘The way on which the girls went, they cut leaves and left them on this way.’ |

||||||||||||

|

[ù |

yé |

fúra |

kári |

k’ |

à |

bìla |

[ò |

síra |

kàn]OBL]MC |

|||

|

3pl |

pfv.aff |

leaf |

cut |

inf |

3sg |

leave |

d.dem |

way |

on |

|||

|

Freely: ‘The girls cut leaves and left them on the road that they took’. |

||||||||||||

<41>

There are two different conditional constructions in Bambara distinguished formally: first, a construction displaying the conjunction ní ‘if’, and second, a clause showing the auxiliary mána [27]. Clauses introduced by the conjunction ní occur most often initially; in rare cases the order is inverted, so that they follow the MC (Dumestre 2003:380). The conjunction ní can be considered as a subordinator; a clause it introduces cannot function as independent clause. On the contrary, the MC corresponds without any change to an independent clause. If the subordinate part is a verbal clause, the choice of the TAM category depends on the aspectual relation between the conditioning event and the predicted event. If both the event encoded in the conditional and the one in the MC take place at the same time, the conditional contains an imperfective predicate marker (38). If the prediction (expressed in the MC) is such that the conditioning event is expected to be completed before the MC event takes place, the conditional clause bears perfective and the MC imperfective aspect (39), (40), or future tense. As the comparison of (38) with (39) illustrates, the difference of perfective vs imperfective marking in the conditional clause does not correspond to the distinction between course of events conditionals (or the realis type) and hypothetical conditionals (or the irrealis type).

|

(38) |

Bambara. Imperfective aspect in both, the conditional (CEC) and the MC |

|||||||||||||

|

[ní |

í |

bɛ́ |

fíyen |

wéle]COND, |

||||||||||

|

if |

2sg |

ipfv.aff |

blind.person |

call |

||||||||||

|

‘If you call a blind person, |

||||||||||||||

|

[í |

bɛ́ |

mɔ̀gɔ |

fìla |

wéle]MC |

||||||||||

|

2sg |

ipfv.aff |

person |

two |

call |

||||||||||

|

you call two people.’ (Bailleul 2005:196, proverb n°1944) |

||||||||||||||

|

(39) |

Bambara. Perfective in conditional (CEC), imperfective in MC |

|||||||||||||

|

sábu |

[ní |

cɛ̀ |

ní |

mùso |

má |

jɛ̀]COND, |

||||||||

|

because |

if |

man |

and |

woman |

pfv.neg |

have.sexual.relations |

||||||||

|

‘Because, if a man and a woman don’t have sexual relations |

||||||||||||||

|

[dén |

tɛ́ |

sɔ̀rɔ]MC |

||||||||||||

|

child |

ipfv.neg |

get |

||||||||||||

|

a child cannot be born.’ [entretien sida 1994_04_10.dis.html, #369611] |

||||||||||||||

|

(40) |

Bambara. ní conditional-perfective in conditional (HC), imperfective in MC |

|||||

|

...[ní |

jà |

ìn |

má |

kɛ̀lɛ]COND, |

||

|

if |

drought |

def |

pfv.neg |

combat |

||

|

‘...if we do not combat the drought (lit.: if the drought is not combatted), |

||||||

|

[jàmana |

tɛ́ |

sé |

kà |

yíriwa]MC. |

||

|

country |

ipfv.neg |

defeat |

inf |

progress |

||

|

the country will not be able to progress.’ (Dumestre & Maïga 1993:7) |

||||||

<42>

The alternative conditional clause displays the conditional auxiliary mána. Its use is restricted to affirmative clauses with verbal predicates, whereas the conjunction ní introduces both affirmative (38) and negative ((39), (40)) clauses, and both clauses with a verbal and a nonverbal predicate (42d) [28]. In the conditionals with mána, no conjunction or other temporal or aspectual marker or copula can be added, and the negative counterpart of the auxiliary has almost fallen into oblivion [29]. To express negative parallels speakers of standard Bambara rather use conditionals with the conjunction ní described above.

|

(41) |

Bambara. Conditional clause with auxiliary mána |

|||||||

|

[í |

ká |

màrifa |

mána |

tíɲɛ]COND, |

||||

|

2sg |

con |

rifle |

cond |

break |

||||

|

‘If your rifle breaks, |

||||||||

|

[à |

bɛ́ |

sé |

k’ |

ò |

dìla]MC |

|||

|

3sg |

ipfv.aff |

defeat |

inf |

d.dem |

repair |

|||

|

he can repair it.’ (Bird, Hutchison & Kante 1977) |

||||||||

<43>

The copula of a clause with a nonverbal predicate (42a) cannot simply be combined with or substituted by the auxiliary mána (42b). mána can be used, when the copula is replaced by the verb kɛ́ ‘happen, become, do’ (42c); otherwise the alternative construction bearing the conjunction ní is used (42d).

|

(42) |

a) |

Bambara. independent clause with nonverbal predicate and copula bɛ́ [b’] |

|||||||

|

kìbaru |

b’ |

í |

fɛ̀ |

||||||

|

news |

cop.loc.aff |

2sg |

pp |

||||||

|

‘you have got news’ |

|||||||||

|

b) |

impossibility to use mána with a nonverbal predicate |

||||||||

|

*kìbaru |

mána |

(b’) |

í |

fɛ̀ |

|||||

|

news |

cond |

cop.loc.aff |

2sg |

pp |

|||||

|

c) |

mána-conditional clause with nonverbal predicate; copula replaced by verb kɛ́ |

||||||||

|

kìbaru |

mána |

kɛ́ |

í |

fɛ̀ |

|||||

|

news |

cond |

do |

2sg |

pp |

|||||

|

‘if you have got news’ |

|||||||||

|

d) |

conditional with the conjunction ní, clause with nonverbal predicate |

||||||||

|

ní |

kìbaru |

b’ |

í |

fɛ̀ |

|||||

|

if |

news |

cop.loc.aff |

2sg |

pp |

|||||

|

‘if you have got news’ |

|||||||||

<44>

Although generalizing relative clauses are frequent in Bambara, the construction was not expressly discussed in Dumestre’s (1987, 2003) grammar. The first examination of the topic is found in Vydrin’s (2019) “Cours de grammaire bambara”. Vydrin follows Creissels (2009) and Creissels & Sambou (2013) who studied the corresponding construction in Malinké of Kita and Mandinka calling it “construction relative généralisante” (generalizing relative construction). The generalizing relative is described as a construction combining features of a relative and a conditional and meaning ‘the one who’, ‘any X who’ or ‘if there is a X that …’ (Vydrin 2019). The feature characteristic of conditionals found in this construction is the marking by means of the conjunction ní (43-46) or the auxiliary mána (47); the feature characteristic of relative clauses, a relativized NP marked by the relative morpheme mîn, and a NP coreferential with the RC in the MC.

<45>

Showing the deictic demonstrative ò, the coreferential NPs in the MCs are similar to those in sentences showing typical relatives. Furthermore, some show an element stressing the general meaning, expressing a higher-order category, i.e. tìgi ‘person, agent’ in (43), or mùso ‘woman’ in (45), always accompanied by the deictic demonstrative ò. Alternatively the second person singular pronoun í stands for an impersonal pronoun (44) ‘the one, the person concerned’. A plural head is sometimes referred to by the pronoun òlu ‘they’ (46).

|

(43) |

Bambara. (ní-) CRC modifying the subject, coreferential in MC: ò tìgi |

|||||||

|

[ní |

[mîn]S |

yé |

dɔ̀nkili |

dá |

dɔ́rɔn]CRC, |

|||

|

if |

rel |

pfv.aff |

song |

sing |

only |

|||

|

‘Whoever only sings the song, |

||||||||

|

[[ò |

tìgi]S |

bɛ́ |

fàga]MC |

|||||

|

d.dem |

agent |

impf.aff |

kill |

|||||

|

must die (lit.: the one will be killed).’ [npogotiginin kokɔrɔbɔla] |

||||||||

|

(44) |

Bambara. (ní-) CRC modifying the subject mɔ̀gɔ ‘person’, coreferential in MC: í |

|||||||||

|

[ní |

[mɔ̀gɔ |

mîn]S |

kɛ́ra |

dònso |

yé]CRC |

kó |

||||

|

if |

person |

rel |

become-pfv.aff |

hunter |

pp |

say |

||||

|

‘Whoever ~ anyone who becomes a hunter, |

||||||||||

|

[ɲáma-gɛn-fura |

ká |

yé |

[í |

fɛ̀OBL]MC |

||||||

|

negative.force-chase-medicine |

subj |

see |

2sg |

pp |

||||||

|

should be in possession of a medicine to chase away negative forces. |

||||||||||

|

(45) |

Bambara. (ní-) CRC modifying the subject, coreferential in MC: mùso (superordinate category [30]) |

|||||||||||||

|

[ní |

[mîn]S |

kó |

à |

yé |

ù |

wólo |

kúngo |

kɔ́nɔ]CRC |

||||||

|

if |

rel |

say |

3sg |

pfv.aff |

3pl |

give.birth |

forest |

in |

||||||

|

‘Whoever says she has born them in the wilderness, |

||||||||||||||

|

... |

[[ò |

mùso]CS |

yé |

ù |

bá |

yé]MC |

||||||||

|

d.dem |

woman |

cop |

2sg |

mother |

pp |

|||||||||

|

this woman is their mother.’ Freely: ‘The woman who pretends to have born them |

||||||||||||||

|

(46) |

Bambara. (ní-) CRC modifying the oblique; coreferential in MC: pronoun òlu |

||||||||

|

[ní |

wùlu |

dòn-na |

dú |

mín |

kɔ́nɔ], |

[à |

b’ |

||

|

if |

dog |

enter-pfv.aff |

compound |

rel |

in |

3sg |

ipfv.aff |

||

|

‘Whatever compound the dog enters, he directly goes toward |

|||||||||

|

í |

ɲɛ́sin |

[òlu]GEN |

ká |

súrɔfana |

sìgi-len |

mà] |

|||

|

refl |

orient |

3pl.emph |

con |

dinner |

put-part |

pp |

|||

|

their (the compound’s members’) served dinner’ (Dunbiya & Sangare 1996:53) |

|||||||||

<46>

The coreference in the last example builds on the metonymic relation between dú ‘compound’ as a place where the dog enters and dú ‘family’, represented by òlu ‘they’ as the people living in one compound and who the dinner has been prepared for.

<47>

Like in the Senufo languages discussed above, Bambara relatives are correlative constructions. The typical RC precedes the MC. The head is marked by means of the relative morpheme mîn / mínnù ~ múnnù originating in a deictic demonstrative, which is still in use in this function in another Manding variety. In a Bambara RC, mîn has subordinating function, and its position signals the syntactic role relativized. The main difference vis-à-vis the Senufo languages is the strict word order in Manding. A coreferential NP in the MC usually consists of or is determined by the discourse demonstrative ò.

<48>

There are two types of conditionals, one introduced by the conjunction ní ‘if’, possible with all clause types and both polarity values, and another one that shows the (affirmative) conditional auxiliary mána, which is restricted to verbal clauses.

CRCs are possible with either conditional marking. The other features of the clause correspond to those of RCs.

<49>

In the previous sections of this paper I have shown that several Gur and Mande languages spoken in large areas in West Africa have a type of relative clause that is additionally marked as conditional. These languages are Syer and Supyire, two varieties belonging to the Senufo group (Gur), and Bambara as a representative of Manding (Mande). According to formal reasons the relevant construction was called the conditional-relative clause. From a functional point of view these constructions are said to be nonreferential (Carlson 1994) or generalizing relative clauses (Creissels 2009, Creissels & Sambou 2013, Vydrin 2019). Such ‘generalizing’ relative clauses translate into English with a pronoun that comprises the element -ever as in whoever, whatever, related to the representative-instance quantifier every, or any X that, comprising another quantifier of the same type, any.

The question to be answered in this section is how the generalizing function of CRCs is brought about in the three languages presented above. Therefore, it is worthwhile resuming the functions of each of the formal components making up the conditional-relative clauses.

<50>

On the one hand, the conditional expresses a hypothetical event, i.e. an event abstracted from a concrete, real situation. It creates a hypothetical mental space, which is distinct from current reality and establishes a particular viewpoint by removing the situation from the current reality of the actual speech event (Langacker 1997:220-221). The two main subtypes of conditionals discussed above are the hypothetical conditionals (HCs) and the course of events conditionals (CECs). The HCs represent hypothetical non-factual events. The CECs, bearing the same hypothetical encoding, reflect habitual or generic situations resulting from former real instances of an event type that have occurred at specific points in time. The similarity of encoding of these two subtypes provides evidence of the possibility for hypothetical events to be interpreted as general, habitual or universally valid events, provided they are combined with some higher-order terms and/or the appropriate tense-aspect marking.

Thus, the Bambara proverb (38) ‘If / when(ever) you call a blind person, you call (in fact) two people’ results from the observation of several instances of a scene where a blind person comes in the company of a child guiding him or her to the one who requests him/her to come. Nevertheless, it is also valid when the speaker him/herself never observed a concrete event of this type. Building up a hypothetical mental space (Fauconnier 1995, Langacker 1997) triggered by the conditional auxiliary in Syer, Supyire and Bambara or by means of the conjunction ní ‘if’ in Bambara, the speaker detaches the situation from all concrete occurrences and thereby generalizes it.

<51>

On the other hand, a RC modifies clausally a participant of an event that has a syntactic role in the MC. But this syntactic role is only indirectly represented in it by means of a coreferential NP. The relative morpheme corresponding to the interrogative in Syer, to the (extended) demonstrative in Supyire and the unique relative morpheme, originating in a presently obsolete demonstrative in Bambara signals which argument of the clause will be co-referred to in the MC, i.e. about which one the speaker wants to tell something in the MC. The RC modifies and thereby restricts the referent among other entities belonging to the same type. The type of entity is either specified lexically, when the head is overtly mentioned, or only schematically, when the head is replaced by the relative pronoun. The event expressed in the MC holds for the entity restricted by the event expressed in the RC.

<52>

The CRC makes use of both the function of the conditional as a means to abstract from concrete instances of an event type and of the relative as a means to restrict the referent of a type of entity. In the CRC, the conditional encoding conveys the modifying event a hypothetical property; a particular type is restricted by the hypothetical property. By a clause meaning ‘hypothesize an entity X restricted by the hypothetical event expressed in the RC’, abstraction is made from a concrete individual, because an entity that is modified by a non-actual event is itself non-actual. This means it can be any entity of the given type, under condition that the hypothetical restriction applies. The coreferential NP in the MC refers to such a hypothetical or non-actual entity and the MC predicts something upon such a non-actual and consequently generalized entity.

In English generalizing relatives every X that, any X that the generalization is achieved through the representative-instance quantifiers [31] every, any, a, which stand for any member of a particular type restricted or modified by the event expressed in the RC. In the three languages discussed above generalization of a property attributed to a type is achieved by presenting this property as hypothetical.

|

Abbreviations |

|||

|

Numbers before an abbreviation indicate 1st or 2nd (or, in Bambara 3rd) person pronouns, numbers following an abbreviation stand for the noun class of the referent. |

|||

|

1sgs |

first person singular subject |

inter |

interrogative morpheme |

|

1sgns |

first person sing. non-subject |

ip |

intransitive prefix |

|

aff |

affirmative |

ipfv |

imperfective |

|

ag |

agent |

it |

itive |

|

Aux |

auxiliary |

L |

low tone |

|

con |