The sociolinguistic situation of ǂHoan, a moribund 'Khoisan' language of Botswana [1]

urn:nbn:de:0009-10-31645

Zusammenfassung

Im Jahr 2010 führten wir eine Studie zur soziolinguistischen Situation der stark vom Aussterben bedrohten "Khoisan"-Sprache ǂHoan (Ju-ǂHoan) durch, die in Botswana am Rande der Kalahari Wüste gesprochen wird. Das Ziel der Studie war mehr über den Sprachgebrauch und die Verbreitung von Vielsprachigkeit, sowie über die Einstellung der ǂHoan-Sprecher zu ihrer Sprache, herauszufinden. Die Daten wurden auf der Grundlage eines Fragebodens erhoben. Wir fanden heraus, dass die positive Einstellung einzelner Sprecher gegenüber ǂHoan häufig der Einstellung der Gemeinschaft zu dieser Sprache entgegensteht, was zu einem unterschiedlichen Sprachgebrauch im familiären und formalen Kontext führt. Alle ǂHoan Sprecher sind mindestens bilingual, indem sie neben noch die lokale lingua franca Kgalagadi (Bantu) sprechen. Die meisten Sprecher sind sogar trilingual und sprechen neben diesen beiden Sprachen auch noch Gǀ(Khoe-Kwadi). Die meisten unserer Ergebnisse stimmen mit den Ergebnissen der früheren Studie zur soziolinguistischen Situation von Batibo (2005a) überein. Die Datenerhebung dieser Studie fand im Jahr 2003 statt. Durch einen Vergleich unserer Ergebnisse mit denen von Batibo (2005a) werden Veränderungen der soziolinguistischen Situation des ǂHoan unter der Berücksichtigung verschiedener Dorfgemeinschaften, aufgezeigt.

Abstract

In 2010, we conducted a sociolinguistic survey on the moribund 'Khoisan' language ǂHoan (Ju-ǂHoan), spoken in Botswana at the fringe of the Kalahari Desert. The survey aimed at investigating language use, degrees of multilingualism and language attitude among the ǂHoan speakers. Data collection was done on the basis of a questionnaire. We found that the positive language attitude of individuals towards ǂHoan often conflicts with the community's attitude towards this language, resulting in a split of actual language use between the family and more formal situations. All ǂHoan speakers are at least bilingual speaking the local lingua franca Kgalagadi (Bantu) besides ǂHoan. Most of them are in fact even trilingual, speaking Gǀui (Khoe-Kwadi) in addition to ǂHoan and Kgalagadi. Most of our results stand in line with an earlier sociolinguistic survey on ǂHoan by Batibo (2005a) which was carried out in 2003. In comparing Batibo's results to ours, changes in the sociolinguistic situation of ǂHoan as well as differences between the different villages will be pointed out.

<1>

ǂHoan is a severely endangered language spoken in the Kweneng District of Botswana, located at the fringe of the Kalahari Desert. According to Batibo (2005b) it is one of the most critically endangered languages of Botswana.

<2>

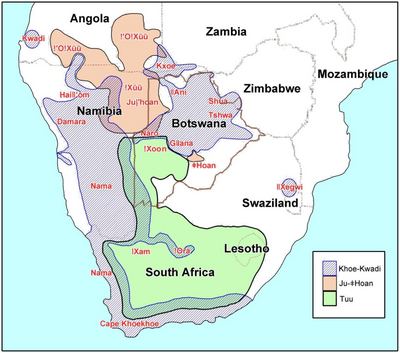

For a long time ǂHoan was assumed to be an isolate language that could not be shown to be related to any of the other Khoisan languages. [2] , [3] This was partly due to the lack of linguistic material and general information about the language and its structure. In 2010, however, Heine & Honken finally published an article showing that ǂHoan is related to the Ju languages (Greenberg's Northern Khoisan). They argue for a language family called the Kx'a family using the comparative method to reconstruct "some traits of phonology" (Heine & Honken 2010:6). The proposed Kx'a language family (kx'aa is a shared lexeme meaning 'ground' or 'soil') includes the languages ǃXuun and ǂHoan. Other authors, e.g. Güldemann (2008), subsume the Ju languages and ǂHoan under the label 'Ju-ǂHoan'. Map 1 shows the historical distribution of the languages belonging to the Khoisan lineages.

|

Map 1: Historical distribution of major Khoisan linguistic groups in southern Africa |

|

|

|

|

|

based on Güldemann & Vossen (2000) |

|

<3>

So far, ǂHoan is only poorly documented. In fact, according to Güldemann & Vossen (2000), it is one of the least described Khoisan languages still spoken today. Apart from a few articles looking at specific grammatical constructions (Gruber 1973, 1975a; Collins 1998, 2001, 2002 and 2003; Collins & Bell 2001), there is also a very short treatment of major aspects of ǂHoan grammar by Collins and an unpublished word list by Gruber (1975b). Neither a grammar nor anything on the complex topic of phonetics and phonology has yet been published.

<4>

This sociolinguistic survey was carried out as part of a linguistic research project documenting ǂHoan and examining the outcome of the ongoing language contact with its geographically neighboring languages.

<5>

The main motivation was the fact that it is highly important for the field of contact linguistics to have detailed descriptions not only of the languages themselves, but also of the sociolinguistic settings in which the languages are spoken when language contact is taking place. Furthermore, this sociolinguistic study was conducted in order to see how the situation of ǂHoan and its speakers has changed since Batibo conducted his survey in 2003. An additional aim was to include speakers of villages that Batibo did not include when he did his survey. This is the only way in which one will be able to see which factors may have had an impact on the contact situation. Eventually, a detailed sociolinguistic description is essential for interpreting linguistic data in a language contact situation.

<6>

Additionally, the transcriptions of the ǂhoan recordings by Sands (2005), which she kindly made available to us, systematically differ from our transcriptions. Since Sands recorded speakers from a different village, the question arose whether there may be some phonetic variation between the ǂHoan spoken in different villages. The most systematic difference is that Sands' sibilants and affricates are always post-alveolar while our data show the alveolar counterparts. (1) and (2) give some examples of the transcriptional differences between Sands' (2005) and our data.

|

(1) |

Present study |

Sands (2005) |

|

tsíí |

tʃi |

|

|

(to) see |

to see [4] |

|

|

(2) |

Present study |

Sands (2005) |

|

zòò |

ʒo |

|

|

water |

water |

<7>

Comparing Sands' recordings to our recordings suggests (at least on the basis of present state of documentation) that there is no (or rarely) an actual difference in pronunciation. It is, however, generally noticeable that there is variation in the pronunciation of certain phonemes within the utterances of one speaker as well as between speakers. These variations, which concern the manner of articulation and voicing, occur most frequently with sibilants and affricates, i.e. /z/ can be either pronounced [z], [Ʒ] or (at least partially) devoiced as [s]. Thus, the examples above display exactly such a variation. Depending on how often one or the other phone occurs, one will eventually choose one as the phoneme (which will thus be the variant used in the transcription). This is a possible explanation for the transcriptional differences between us and Sands. Although there is still very little data from Salajwe, it can already be observed that the Salajwe speaker (number 12 in Table 1 below) consistently uses [ʃ] where all other consultants tend to use [s].

<8>

Additionally, as mentioned above, Collins (1998) as well as Batibo (2005a) report the existence of a closely related language or dialect of ǂHoan called Sasi. The search for speakers was thus extended further to the north towards the Khutse Game Reserve in order to investigate potential phonetic variation in the language or differences in the sociolinguistic setting.

<9>

The survey was conducted in August and September 2010. The questionnaire was conducted with 13 of the 15 fluent speakers we met. The remaining two speakers were sick at that time and therefore not able to participate in the survey. In contrast to Batibo, we only included fluent speakers and did not conduct the questionnaire with non-fluent or non-speakers of ǂHoan [5].

<10>

The questionnaire consists of 69 questions covering the following topics:

-

Relevant personal data, i.e. (approximate) age or age group, family status, present and former place(s) of residence and level of formal education

-

Language use in the generations of the consultants' parents and grandparents as well as the language use of the consultants with the younger generations

-

Language use in different domains of everyday life

-

Language attitude

-

(Self-estimated) language proficiency

<11>

The basis of the questionnaire is a modified version of a sociolinguistic questionnaire developed by Brigitte Pakendorf that she kindly made available to us. Changes were made mainly on the basis of Blair (1990) and Grimes (1995) and in order to adapt the questionnaire to a southern African cultural context.

<12>

In addition to the questionnaire, a short word list of 58 items was elicited with six of the speakers. This was mainly done in order to get initial data on potential dialectal variation between the ǂHoan spoken in different places. The word lists were recorded with three speakers in Khekhenye and due to time limitations with one speaker each in Tswaane, Dutlwe and Salajwe.

The data was entered into a file maker data base.

<13>

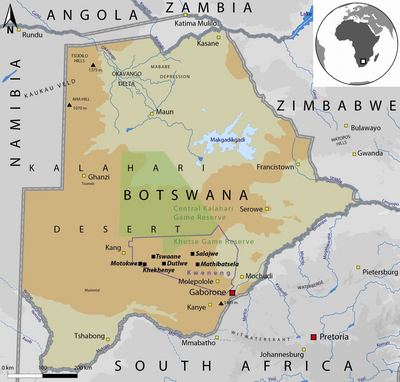

Today ǂHoan speakers are mainly found in the Kweneng District, in particular in the area adjacent to Kang, the regional centre [6]. The villages and settlements are located along a quite recently reconstructed and now tarred road connecting the Trans Kalahari Highway and Letlhakeng. Speakers were found in the following villages along this road: Motokwe, Khekenye, Tswaane, and Dutlwe (cf. Map 2). Three more speakers were found in the villages of Mathibatsela and Salajwe. In the latter village there are supposedly some more speakers that were absent when we visited in September 2010. Furthermore, we met some non-fluent speakers in Khudumelapye. In other villages around this area it is still known that this language existed but no more speakers can be found. We can, however, not exclude that there are some more speakers in other, even more remote areas that we were not able to visit or do not know of. Most of the older speakers at least were still born inside of what is nowadays the Khutse Game Reserve or the Central Kalahari Game Reserve and only moved southwards when they had to leave the reserves from the mid 1990s on.

<14>

Collins (1998) reported that some speakers could be found in Tsia. When we visited Tsia in 2010, we found that Tsia is not a village but a cattle post, i.e. a non-permanent settlement where people stay for some nights in order to take care of their cattle. No speaker could be found and the two people that were present there did not know of anyone who speaks ǂHoan.

|

Map 2: ǂHoan language area |

|

|

<15>

According to Collins (1998) and Batibo (2005a), the language (or dialect) most closely related to ǂHoan is called Sasi. This language is reported to be spoken in the south-eastern villages Lethajwe and Artesia (south of Shoshong) by Collins (1998) and in Serowe by Batibo (2005a). So far, however, no data of this language has been published and none of our consultants knew anything about this language. Additionally, Collins (1998) does not give any source for this information and Batibo (p.c.) got this information from his consultants but did not personally try to find the speakers. Thus, these villages are still to be visited. Note also, that Sasi is the Kgalagadi name for the Taa language and ǀaati (of which sasi could be a 'simplified Tswana pronunciation') is the ǂHoan word for 'Khoisan language'. Therefore, it is uncertain whether Sasi as a closely related dialect or language really exists or whether the term simply refers to Taa or other Khoisan languages in general.

<16>

The number of speakers does not amount to more than 50 who are mainly between 60 and 70 years old. The number reported here is only an approximate estimation. The estimated number of 50 speakers is made up on the basis of the following numbers: there are about 15 fluent speakers (all met in person) and about 20 non-fluent speakers. The remaining 15 were included for the speakers and semi‑speakers [7] that we have not met and that could potentially be found in some places that were not included in this survey, i.e. for example in areas inside the Khutse Game Reserve. Batibo (2005a) still reports a number of between 120 and 200 speakers. This might be interpreted as a tremendous decrease of the number of speakers during the last seven years. The source of Batibo's data is, however, not clear since he does not cite any census. Thus, neither the numbers of speakers nor the apparent rate of decrease during the last years can be considered to be precise.

<17>

ǂHoan is no longer passed on to the younger generations and is therefore no longer learnt as mother tongue (L1). The mother tongue of the majority of children is the Bantu language Kgalagadi (S.31d), which is also the lingua franca of the region. According to Batibo (2005a), not only the ǂHoan speakers but also the speakers of all the other Khoisan of this region (i.e. / ǃXoon [8], Naro, Gǀui and Gǁana) are fluent in Kgalagadi.

<18>

Batibo cites Anderson & Janson (1997) who state that the ǂHoan speakers were present in the Kweneng district already before the first Bantu speaking people arrived approximately 1000 years ago. He also claims that at that time the only other Khoisan language spoken around that area was ǃXoon. According to Traill and Nakagawa (2000) there are also indications for more recent contact situation between ǂHoan and Gǀui speakers at a pan west of the Khutse Game Reserve until about 60 years ago. The interviews with our consultants strengthen the assumption that there has been intense contact between these groups (cf. section 'Multilingualism').

<19>

The individuals belonging to the speech community of ǂHoan live scattered over at least six villages (mentioned above) that are quite distant from each other (i.e. the minimal distance between two villages is 7 km, the maximal distance is more than 100 km). Frequent contact between ǂHoan speakers is thus only possible for those living in the same (or maybe the neighboring) village. This results in a situation where most of the communication involving ǂHoan speakers takes place between them and speakers of other languages in the village, and so communication in ǂHoan occurs only infrequently.

<20>

All consultants participating in our study are multilingual in the sense that they are fluent in at least one more language in addition to their mother tongue ǂHoan. Most of the ǂHoan consultants are trilingual, i.e. they speak Gǀui (Khoe-Kwadi) and Kgalagadi (Bantu) fluently besides ǂHoan. The consultants from Salajwe (cf. Table 1, speakers 12 and 13) form the only exception, since they do not speak Gǀui; however, one of them (speaker 13) does have some passive knowledge of Taa (Tuu) instead. Batibo (2005a) already reported that all of his ǂHoan consultants were trilingual, but besides ǂHoan and Kgalagadi he reports that his consultants also speak Tswana [9]. Batibo does not state how he judged his speakers' ability of speaking Tswana (i.e. whether he actually tested them or whether he relied on their self-estimation like we did). In the present survey, however, only three speakers clearly stated that they were able to speak Tswana, while most of them said they would understand the language at least to a certain extent (cf. Table 1) but are not able to speak it. This is due to the fact that Tswana and Kgalagadi are very closely related languages, so that speakers of these languages can adapt to each other quite easily. The observation that all ǂHoan speakers that participated in the our study also speak Gǀui has not been reported by Batibo. His tables actually imply that some of the speakers are able to speak another language (other than Kgalagadi and Tswana) since he has the category "other". There is, however, no explicit explanation of what "other” includes [10]. This is due to the fact that he was mainly interested in the ǂHoan speakers shifting to Kgalagadi (in contrast to his expectation that they would shift to the national language Tswana).

<21>

Concerning the multilingualism of the ǂHoan speakers, it is noteworthy that until approximately the early 1970s (i.e. already before they started shifting to Kgalagadi) there actually was an asymmetrical bilingual situation with ǂHoan speakers acquiring Gǀui, but only a few Gǀui speakers learning ǂHoan (Nakagawa, p.c.) [11]. This asymmetrical bilingual situation is still found with the fluent ǂHoan speakers today, the difference being that we did not meet Gǀui speakers who also speak ǂHoan.

Table 1 summarizes the languages that the consultants speak in addition to ǂHoan and their self-estimated language proficiency in speaking and understanding them.

|

Table 1: Languages other than ǂ Hoan and self-estimated proficiency |

|||||||||||

|

speaker |

sex |

Kga |

Tsw |

Gǀui |

Taa |

Fan |

|||||

|

S |

U |

S |

U |

S |

U |

S |

U |

S |

U |

||

|

1 (42) |

m |

y |

y |

n |

y |

y |

y |

n |

n |

n |

n |

|

2 (~65) |

f |

y |

y |

n |

(y) |

y |

y |

n |

n |

n |

n |

|

3 (42) |

f |

y |

y |

(y) |

y |

y |

y |

n |

n |

n |

n |

|

4 (~69) |

f |

y |

y |

n |

y |

y |

y |

n |

n |

n |

n |

|

5 (~60) |

m |

y |

y |

n |

y |

y |

y |

n |

(y) |

y |

y |

|

6 (~82) |

m |

y |

y |

n |

(y) |

y |

y |

n |

n |

y |

y |

|

7 (44) |

m |

y |

y |

y |

y |

n |

y |

n |

n |

n |

n |

|

8 (~68) |

m |

(y) |

y |

n |

y |

y |

y |

n |

n |

y |

y |

|

9 (50) |

m |

y |

y |

n |

n |

y |

y |

n |

n |

n |

n |

|

10 (~60) |

m |

y |

y |

y |

y |

y |

y |

y |

y |

y |

y |

|

11 (~60) |

m |

y |

y |

n |

n |

(y) |

y |

n |

n |

y |

y |

|

12 (~65) |

m |

y |

y |

y |

y |

n |

n |

(n) |

y |

y |

y |

|

(13 (~60) |

f |

y |

y |

n |

n |

n |

n |

n |

n |

n |

n) |

|

S = speak, U = understand, () = unclear judgment; Kga = Kgalagadi, Tsw = Tswana, Fan = Fanakalo; numbers in brackets indicate the age or approximate age of the speakers |

|||||||||||

<22>

Table 1 shows the following about the patterns of multilingualism:

-

As already mentioned above, almost all of the ǂHoan speakers also speak at least Kgalagadi and Gǀui, with the exception of speakers 12 and 13 who neither speak nor understand Gǀui. Concerning the question where they learnt Gǀui and Kgalagadi, the answers are almost always identical: Gǀui was learnt in their childhood while playing with Gǀui children, and Kgalagadi was learnt later in life when they were working for the Kgalagadi people.

-

Only one of the consultants speaks Taa (number 10), and one of them says that he fully understands it (number 13). Speaker number 10 said that he learned Taa while working in the mines in South Africa. Unfortunately, for speaker number 12 we lack the information of where he learned Taa. The lack of bilingualism between ǂHoan and Taa is an interesting fact, since at least nowadays, speakers of all three languages (ǂHoan, Gǀui and Taa) live together in mixed settlements. This might thus suggest, that the contact between ǂHoan and Taa is rather recent or that historical contact between the two groups did at least not result in a stable bilingual situation. There are, however, a number of parallel structural features between the languages belonging to the Ju-ǂHoan and the Tuu lineages (and thus also between ǂHoan and Taa). Stating that these parallel structural features are "not necessarily tied to a common genetic origin" Güldemann & Vossen (2000:108) imply that they might have evolved through language contact.

-

As already mentioned above, the self-estimated proficiency of Tswana is not easy to judge since the language is very similar to Kgalagadi. Thus, all of them are able to understand Tswana to some extent, but almost none of the consultants are actively able to speak it. Potential exceptions are the youngest consultants, who are more regularly exposed to Tswana since their children learn Tswana at school and tend to use it amongst each other (speaker 1 and 3).

-

The reason why all of the elder male ǂHoan speakers know Fanakalo to some extent is that they went to South Africa and worked in the mines (speaker 5, 6, 8, 10, 11 and 12). Fanakalo is a pidgin that originated in South Africa in the 1820s as a means of communication between the Afrikaaners, the English and Xhosa [12] speakers. From around 1870 on it was used in the South African mines where people speaking languages belonging to distinct language families worked together and thus communicated with each other (Kaltenbrunner 1996:16ff.).

<23>

Table 2 summarizes the languages spoken by the parents and grandparents of the consultants. Please keep in mind that these numbers of course do not rely on self-estimations, but on the judgments and the memory of our consultants. Additionally, at least for the generation of the grandparents it was not asked for every single person (i.e. languages of father's mother, languages of father's father etc.) but just for the languages of the father's parents. Furthermore, it might be the case that some of the consultants mentioned only the L1 of their parents and grandparents, while others clearly gave an exhaustive list of the languages spoken.

|

Table 2: Languages of parents and grandparents |

|||||||||||||

|

languages of: |

ǂHoan |

Gǀui |

Taa |

Kga |

Tsw |

Fan |

n.a. |

||||||

|

L1 |

Ln |

L1 |

Ln |

L1 |

Ln |

Ln |

Ln |

Ln |

Ln |

||||

|

- father |

12 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

- |

1 |

9 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|||

|

- father's parents |

9 |

- |

2 |

2 |

2 |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

2 |

|||

|

- mother |

12 |

1 |

- |

7 |

1 |

2 |

10 |

1 |

- |

1 |

|||

|

- mother's parents |

12 |

- |

- |

3 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

1 |

|||

|

n.a. = no answer, L1 = mother tongue, Ln = all languages which are not the mother tongue |

|||||||||||||

<24>

The following conclusions can be drawn from Table 2:

-

The mother tongue of almost all of the parents and grandparents of our consultants is ǂHoan. This suggests that it was not so common in the parents' and grandparents' generation to marry someone speaking a different Khoisan language. Table 2 that in the parents' generation only two individuals were not L1 ǂHoan speakers, i.e. one Taa and one Gǀui speaker, while in the grandparents' generation four individuals were not ǂHoan speakers, i.e. two Taa and two Gǀui speakers. Interestingly, although the ǂHoan speakers have been living in close neighborhood with the Kgalagadi for a long time, there has been no intermarriage between the two groups. This might be due to the unequal social status of the two groups, with the Kgalagadi being the areally dominant and thus superior group. note, however, that possible cases of ǂHoan women who married Kgalagadi men and gave up their mother tongue would not have been detected in our survey since we only interviewed ǂHoan speaking individuals.

-

Table 2 suggests that may not have been as common in the past as it is today. This is especially obvious considering the numbers given for the knowledge of Kgalagadi: while most of the individuals in the parents' generation were able to speak Kgalagadi, only two individuals of the grandparents' generation had some knowledge of it. However, it has to be considered that this can be due to the fact that the consultants simply don't know or cannot remember how many and which languages their grandparents were able to speak.

-

A last interesting observation is that only one of the fathers of the consultants is able to speak Fanakalo. This suggests that it was not yet common in this generation to go to South Africa in order to work in the mines. From the age of the consultants it is possible to infer that the first ǂhoan speakers went to the South African mines in the 1940s with a peak of work-related migration in the 1960s.

<25>

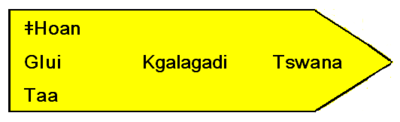

"A study of language use seeks to describe the choices that people make about what speech varieties to use in particular situations." (Blair 1990:107). Language use is, however, also connected to language attitudes. Language attitudes are the opinions of individuals about why a certain language or language variety is more appropriate in a particular situation or domain (Blair 1990). It also has to be kept in mind that an individual speaker can rate a certain language differently than the same language is rated by his community (for further discussion see section 'Language attitude' below).This is connected to the prestige a certain language has in a community. Thus, a speaker can have a positive attitude towards his mother tongue even though this language is of very low prestige within the society or community. Figure 1 shows the prestige of the languages spoken in the surveyed villages (growing level of prestige from left to right).

|

Figure 1: Prestige of languages |

|

|

<26>

The levels of prestige of the languages in Figure 1 are based on the following observations:

-

We often observed that people try to hide their own or their children's 'Khoisan' origin, which indicates that they consider the 'Khoisan' languages of the area (i.e. ǂHoan, Gǀui and Taa) as not prestigious. This observation is supported by Güldemann & Vossen (2000:105) who report the following:

"In modern times, social marginalisation and stigmatisation largely characterise the life of the Khoisan-speaking minorities. In Botswana, for instance, low social prestige and political insignificance find a formal expression in the contemptuous label 'Basarwa', which in a wider sense denotes people at the lowest level of the social ladder, but in a narrower sense refers to Khoisan speakers in particular."

-

We consider Kgalagadi to have a higher prestige, because we observed that this language enables people to communicate in regional centers like Kang. Furthermore, it enables people to get one of the few paid jobs in the area since the employers are usually Kgalagadi people or the government of Botswana.

-

Tswana is considered to be the most prestigious language since it is used in the education system, the language of officials and is one of the national languages of Botswana. It is also the language of the mass media which are slowly gaining importance even in the more rural areas of Botswana. It (potentially) enables people to get a higher education and well-paid jobs.

<27>

This section aims at summarizing which language or languages the ǂhoan consultants choose in a variety of specific situations or domains. The domains that were considered in this survey are summarized in Table 3 below.

Note that for all the questions summarized in the following tables multiple answers were permitted.

|

Table 3: Language use in different situations/domains |

|||||

|

Which language do you use: |

|||||

|

ǂHoan |

Kga |

Gǀui |

Tsw |

n/a |

|

|

- with relatives |

9 |

5 |

5 |

- |

- |

|

- with spouse |

7 |

2 |

5 |

- |

3 |

|

- with relatives of spouse |

3 |

3 |

6 |

- |

3 |

|

- with friends |

11 |

7 |

5 |

- |

- |

|

- in the village |

7 |

10 |

5 |

1 |

- |

|

- with strangers |

2 |

11 |

1 |

4 |

- |

|

- at church |

4 |

4 |

2 |

4 |

7 |

|

- in the shops |

- |

13 |

- |

3 |

- |

|

- at the clinic |

- |

10 |

- |

6 |

- |

|

- with officials |

1 |

10 |

- |

5 |

- |

n/a = not applicable

<28>

Our results support Batibo's (2005a) findings that the language which is used most for communication in the villages is Kgalagadi. There is, however, a clear split between the languages used with family members and friends and with other individuals in the village. While within the family ǂHoan (and Gǀui) are used a lot, in all other situations all consultants switch to Kgalagadi (or sometimes even try to adapt to Tswana).

<29>

However, a few more interesting aspects result from the answers summarized in Table 3:

-

In general, the ǂHoan in Khekhenye codeswitch extensively, i.e. they heavily mix ǂHoan with Gǀui and Kgalagadi. Thus, even if consultants said they would only use ǂHoan, for example, it has to be borne in mind that they probably also use the other languages, though perhaps to a lesser extent and might not be aware of switching between the languages. The same holds for the answers to "language(s) used with friends”.

-

There are reasons to assume that the category "friends" and the category "relatives" consist (at least partly) of the same people since basically all the ǂHoan that participated in this survey are related to each other. The same holds for the languages spoken in the village: since some of the consultants' relatives live in the same village, they of course also speak ǂHoan and Gǀui in the village. Still, most of the consultants stated that they would use Kgalagadi (either only or additionally).

-

The table shows that our consultants often said that they would switch to Tswana when communicating with officials or doctors. Note, however, that this does not mean that they are actually able to speak Tswana but that in these situations they consciously try to adapt to Tswana knowing that this is their interlocutor's language.

-

Most of the consultants' spouses are Gǀui speakers (i.e. 5). This explains the high number of Gǀui used for communication within the couples. That the number for ǂHoan is actually higher than the one for Gǀui is due to the fact that the Gǀui speaking spouses understand some ǂHoan so that our ǂHoan consultants can use some ǂHoan when speaking to them (certainly always mixed with a lot of Gǀui). Additionally, it also includes two spouses that are (or were) ǂHoan speakers.

-

'Church' is, as can be seen in Table 3 above, the only category in which all of the possible languages were mentioned. The reason for this is that the language of the service is usually Tswana or sometimes even English (depending on whether the pastor is Tswana or an English speaking missionary), but people are allowed to choose the language they want to pray in. This can either be the mother tongue (in this case ǂHoan) or any other language.

-

All of the shops are owned by Kgalagadi speakers. Thus the language used when buying things can only be Kgalagadi. Tswana is usually only used when the speakers go to a shop in town.

-

Officials as well as the doctors in the clinics always speak either Tswana (or Kgalagadi) or even English since they usually do not come from the region or are foreigners. If no common language can be found, communication will be possible with the help of a translator.

<30>

Table 4 and Table 5 summarize which languages are used in communication with the younger generations.

|

Table 4: Languages used with children and grandchildren |

|||

|

which language(s) do you speak to: |

ǂHoan |

Kga |

Gǀui |

|

- your children |

5 |

9 |

2 |

|

- your grandchildren |

1 |

9 |

- |

|

Table 5: Languages used by children and grandchildren |

|||

|

which language(s) do they speak to you: |

ǂHoan |

Kga |

Gǀui |

|

- your children |

3 |

11 |

1 |

|

- your grandchildren |

- |

10 |

- |

<31>

A comparison of Table 4 and 5 reveals that more ǂHoan is spoken to the children than ǂHoan is used by the children when speaking to their parents. This is supported by the fact that consultants repeatedly state that the children usually reply back in Kgalagadi even if the parents speak ǂHoan to them. Only one consultant (sometimes) uses ǂHoan when speaking to his grandchildren. As Table 5 shows, all of the grandchildren of our consultants only use Kgalagadi. This is due to the fact that their parents (i.e. the consultants' children) never use ǂHoan when speaking to their children so that the language cannot be acquired by them. The reason for this is that being a 'click-speaking' person is highly stigmatized in Botswana and parents do not want their children to be easily recognizable as a mo sarwa [13].

<32>

Although Tswana still does not play a major role in everyday communication in the village, it can be expected to gain importance with the next generation. Tswana is the medium of instruction at school and most of the teachers are from other regions of Botswana (and actually never of 'Khoisan' origin). Thus frequently and regularly being exposed to Tswana strengthens its role for communication between the younger generations in the village.

<33>

Language attitude is the opinion that speakers have about the language or languages they speak, i.e. the attitude they have towards speaking a certain language. The attitude can be seen as being somewhere on a scale between very positive and very negative, i.e. a speaker might also have a slightly positive attitude or be in a neutral position towards a certain language (cf. Blair 1990).

<34>

However, at least for the context of ǂHoan, it has to be borne in mind that language use, i.e. the decision about which language to speak, does not only depend on the attitude of an individual speaker towards a certain language but also on the attitude the community has, i.e. the way the language is rated "from outside". For example, as will become clear from Table 6 to 8 , speakers of ǂHoan generally have a very positive attitude towards their mother tongue. However, since it is not rated positively in Botswana society to speak a Khoisan language, ǂHoan speakers decide not to speak their mother tongue to the younger generations, opting instead for the language of higher prestige, Kgalagadi. This example shows the conflict of an individual speaker of choosing a language according to their own or the community's attitude.

Tables 6 to 8 summarize the answers given to some of the questions investigating the attitude of speakers towards the languages they speak.

|

Table 6: Which language(s) is the most beautiful language? |

||||

|

ǂHoan |

Gǀui |

Tsw |

all languages |

I don't know/no opinion |

|

6 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

|

Table 7: Which language(s) is the most necessary language? |

||||

|

ǂHoan |

Gǀui |

Tsw |

Eng |

I don't know/no opinion |

|

9 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Table 8: Which language(s) should be taught at school? |

||||

|

ǂHoan |

Gǀui |

Tsw |

Taa |

all languages |

|

9 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

<35>

As Tables 6 to 8 show, the attitudes towards ǂHoan are generally positive (it always gets the highest ratings). This interpretation is supported by the following statements about ǂHoan:

-

All of the consultants feel "good" and "very happy" when they hear ǂHoan spoken.

-

Almost all of the consultants feel bad about the fact that parents do not teach ǂHoan to their children anymore.

<36>

As described in the previous sections, there is a very high degree of multilingualism amongst the ǂHoan speakers, with most of them speaking Gǀui and Kgalagadi in addition to their mother tongue. This is not only true for our consultants, but also for the generation of their parents and possibly even for our consultants' grandparents. Another important observation, related to the previous one, is that ǂHoan speakers code‑switch to a large extent between ǂHoan and Gǀui. Since most of the consultants stated that their parents were also able to speak Gǀui in addition to ǂHoan, we suggest that extensive code-switching might already have existed in the parents' generation. These observations are of great value for studies in contact linguistics since they hint towards an intensive and considerably long contact situation of the two languages. The question of how far back this language contact situation reaches, i.e. to the generation of our consultants' grandparents or even further back, cannot be answered here.

<37>

The number of fluent ǂHoan speakers is extremely small and most of them are already old. Moreover, the speakers have only little or no opportunities to use ǂHoan, since the number of speakers that live in one village is very limited. For the communication with children and grandchildren Kgalagadi is used almost exclusively. Consequently, the children and grandchildren of our consultants had no possibility to acquire ǂHoan. This is due to the fact that Kgalagadi (the local franca) and Tswana (one of the official languages of Botswana) are considered to be much more prestigious. The use of Kgalagadi for almost all purposes of communication has led to the immense decay of ǂHoan. The data gathered in our language documentation project show a high amount of Kgalagadi and Tswana loan words (and even some English loan words) reflecting the ongoing language shift and a growing importance of Kgalagadi in the language contact. Considering the age of the remaining fluent speakers, ǂHoan will be extinct approximately within the next 30 years. Therefore, a profound documentation of the language has become exceedingly urgent.

<38>

In addition, we saw that the language attitude of an individual person often conflicts with the actual language use in the community. Although all participants judge their mother tongue positively and state that they 'feel good' or 'very happy' when they hear their language, they have decided not to pass it on to the next generations. Moreover, it can even be observed that parents try to hide the 'Khoisan' origin of their children from their schoolmates and other people in the village. This is certainly due to the negative standing of Khoisan languages and peoples in Botswana. Our results stand in line with Batibo (2005a) who observes that" […] on the one hand they [the speakers of minority languages like ǂHoan] would like to preserve their own identity and traditions, on the other, they want to be part of the wider world; hence the ambivalent attitudes and inconsistent language behaviour." (Batibo 2005a:91). Being part of the wider world means for all participants to be able to speak Kgalagadi for shopping, access to medical and government services and sending their children to school in order to ensure their access to the wider world. The low prestige of ǂHoan further contributes to the decay of the language.

<39>

Finally, the analysis of the word lists, which we recorded with 6 speakers, showed that one speaker, who lives furthest away from the others, consistently uses [ʃ] where all other consultants would use [s]. This observation might be interpreted as a first hint towards remnants of dialectal differences in ǂHoan.

References

Adendorff, Ralph 2002

'Fanakalo: a pidgin in South Africa.' In: Mesthrie, Rajend (ed.) Language in South Africa, pp.179-198 . Cambridge University Press

Anderson, Lars-Gunner and Janson, Tore 1997

Languages in Botswana. Gaborone: Longman Botswana

Batibo, Herman M. 2005a

'ǂHua: a Critically Endangered Khoesan Language in the Kweneng District of Botswana.' In: Crawhall, Nigel and Nicholas Ostler (eds.) Creating Outsiders: Endangered Languages, Migration and Marginalization, pp.87-93. Stellenbosh: Foundation for Endangered Languages

Batibo, Herman M. 2005b

'Language Decline and Death in Africa: Causes, Consequences and Challenges.' Clevedon: Multilingual Matters

Blair, Frank 1990

Survey on a Shoestring. A Manual for Small-Scale Language Surveys. Arlington, Texas: SIL / University of Texas

Collins, Chris 1998

'Plurality in ǂHoan.' Khoisan Forum, Working Papers 9

Collins, Chris 2001

'Aspects of Plurality in ǂHoan.' Language 77,3:456-476

Collins, Chris 2002

'Multiple Verb Movement in ǂHoan.' Linguistic Inquiry 33,1:1-29

Collins, Chris 2003

'The internal structure of vP in Ju|'hoansi and ǂHoan.' Studia Linguistica 57,1:1-25

Collins, Chris

ǂHoan syntax. Unpublished manuscript http://web.archive.org/web/20060907114459/http://ling.cornell.edu/khoisan/hoan/hoan.htm (05.03.2011)

Collins, Chris and Bell, Athur 2001

'ǂHoan and the Typology of Click Accompaniments in Khoisan.' Cornell Working Papers in Linguistics 18:126-153

Dorian, Nancy C. 1973

'Grammatical Change in a Dying Dialect.' Language 49,2:413-438

Lewis, M. Paul (ed.) 2009

Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/web.asp (19.07.2011)

Greenberg, Joseph H. 1950

'Studies in African linguistic classification: VI The click languages.' Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 6,3:223-237

Grimes, Joseph E. 1995

Language Survey Reference Guide. Dallas, Texas: SIL

Gruber, Jeffrey S. 1973

'ǂHṑã kinship terms.' Linguistic Inquiry 4,4:427-449

Gruber, Jeffrey S. 1975a

'Plural predicates in ǂHoan.' Bushmen and Hottentot Linguistics Studies 2:1-50

Gruber, Jeffrey S. 1975b

ǂHoan fieldnotes. Unpublished manuscript

Güldemann, Tom and Rainer Vossen 2000

'Khoisan'. In: Heine, Bernd and Derek Nurse (eds.) African Languages: An Introduction, . pp.99-122. Cambridge University Press

Güldemann, Tom 2008

'A linguist's view: Khoe-Kwadi speakers as the earliest food-producers of southern Africa.' Southern African Humanities 20:93-132

Heine, Bernd and Henry Honken 2010

'The Kx'a Family.'Journal of Asian and African Studies 79:5-36

Kaltenbrunner, Stefan 1996

'Fanakalo – Dokumentation einer Pidginsprache.' Beiträge zur Afrikanistik 53. Veröffentlichungen der Institute für Afrikanistik und Ägyptologie der Universität Wien

Köhler, Oswin 1975

'Geschichte und Probleme der Gliederung der Sprachen Afrikas. Von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart.' In: Baumann, Hermann (ed.) Die Völker Afrikas und ihre traditionellen Kulturen, pp. 135-373. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag

Sands, Bonny 2005

ǂHoan Fieldnotes. Unpublished manuscript

Traill, Anthony 1973

'«N4 or S7»: another Bushman language.' African Studies 32,1:25-32

Traill, Anthony 1974

'Westphal on «N4 or S7?»: a reply.' African Studies 33,4:249-255

Traill, Anthony 1986

'Do the Khoi have a place in the San? New data on Khoisan linguistic relationships.' Sprache und Geschichte Afrika 7,1:407-430

Traill, Anthony and Hirosi Nakagawa 2000

'A historical !Xóõ- ǀGui contact zone: linguistic and other relations.' In: Batibo, Herman M. and Joseph Tsonope (eds.) The State of Khoesan Languages in Botswana, pp.1-17. Publication of the Basarwa Languages Project. University of Botswana / University of Tromsö

Vossen, Rainer 1997

Die Khoe-Sprachen. Ein Beitrag zur Erforschung der Sprachgeschichte Afrikas. Quellen zur Khoisan-Forschung , 12. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag

Westphal, Ernst O. J. 1974

'Correspondence: Notes on A. Traill: «N4 or S7?».' African Studies 33,4:243-247

[1] We gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through the EuroBABEL Programme of the European Science Foundation, as well as by the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. We particularly thank Blesswell Kure for patiently translating during and after the field work and for his amiable way of interacting with the consultants. We would like to thank Maria Mammen for entering the data into the data base.

[2] Note that there has been a discussion about the classification of ǂHoan as a Southern or a Northern Khoisan language for a long time, especially between Traill (1973, 1974) and Westphal (1974). The Ethnologue classifies ǂHoan as a Southern Khoisan language related to ǃXóõ.

[3] The hypothesis that Khoisan is a genealogical phylum as established by Greenberg (1950) is rejected by most of the linguists working on Khoisan languages today. There are, however, well-established genealogical relationships on lower levels, like e.g. for the Khoe languages (Vossen 1997). For further discussion see Güldemann & Vossen (2000). Note that we follow scholars like e.g. Traill (1986) and Köhler (1975) in that we use the term Khoisan as defined by Güldemann & Vossen (2000:102) as "a cover for all non-Bantu as well as non-Cushitic click languages of eastern and southern Africa, but without explicitly adhering to the genealogical implications”.

[4] Sands (2005) elicited t ʃia for 'to see' which is the verb tʃ i 'see' with a perfect marker a.

[5] Note that out of the 41 consultants interviewed by Batibo, 22 were not able to speak the language at all, 9 could only speak with difficulty, 3 had what he calls a "reasonable knowledge" and only 7 were fluent speakers. The number of 7 fluent speakers matches with the number of speakers that we found in the two villages visited by Batibo, Tswane and Dutlwe. Since our questionnaire included a lot of questions concerning language use in different contexts we excluded non-fluent and non-speakers as they use Kgalagadi for all communication purposes.

[6] Note that Kang is actually not located in the Kweneng District but it is still the regional centre. It is the biggest village in the area and located on the Trans Kalahari Highway which facilitates the access to goods.

[7] "Semi-speakers” is used here as defined by Dorian (1973) as someone whose communicative competence is much higher than her/his linguistic competence, i.e. speakers who are able to speak with a reasonable degree of fluency but make a high number of mistakes.

[8] ǃXoon and Taa are two names referring to the same language.

[9] Tswana is a Bantu language and is, in addition to English, the official language of Botswana.

[10] Batibo mentions that "some individuals also became acquainted with other languages such as ǂGana (Khutle), which extends into the area, and some picked up Afrikaans from South Africa or the Afrikaner farms in the Ghanzi District." (Batibo 2005a:88), but he actually never says anything about the speakers ability to speak Gǀui or Taa. (Note that ǂGana is probably a typo and should actually be Gǁana).

[11] According to Nakagawa (p.c.) this information was reported by one of Nakagawa's consultants. Traill and Nakagawa state that Gǀui and ǂHoan people lived together around "q||háàkéná, a pan to the west of the Khutse Game Reserve on the southern border of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve" (Traill & Nakagawa 2000:14).

[12] Note that some authors, e.g. Adendorff (2002), analyze Fanakalo as a pidgin based on Zulu (and English) rather than Xhosa.

[13] mosarwa (pl. basarwa) is the Tswana word used for a person of 'Khoisan' origin often with a slightly negative connotation.

Lizenz

Empfohlene Zitierweise ¶

Gerlach L, Berthold F (2011). The sociolinguistic situation of ǂHoan, a moribund 'Khoisan' language of Botswana. Afrikanistik online, Vol. 2011. (urn:nbn:de:0009-10-31645)

Bitte geben Sie beim Zitieren dieses Artikels die exakte URL und das Datum Ihres letzten Besuchs bei dieser Online-Adresse an.

Volltext ¶

-

Volltext als PDF

(

Größe:

316.1 kB

)

Volltext als PDF

(

Größe:

316.1 kB

)

Kommentare ¶

Es liegen noch keine Kommentare vor.

Möchten Sie Stellung zu diesem Artikel nehmen oder haben Sie Ergänzungen?

Kommentar einreichen.