The Jukun of Kona, the Emir of Muri and the French adventurer: An oral tradition recounting Louis Mizon's attack on Kona in 1892 [1]

urn:nbn:de:0009-10-15736

Abstract

Louis Mizon, a Lieutenant of the French Navy, assisted the Emir of Muri, Muhammadu Nya, in conquering the Jukun of Kona in 1892 in an attempt to expand the influence of France in the region of the Benue river. The Emir had besieged Kona in vain for six years, but with the superior military technology at Mizon's disposal, the town was subjugated. It was a traumatic event which is preserved in the oral traditions of the Jukun until today. The essay presents an oral text recorded in 1996, placing it in the historical context and offering interpretations.

Résumé

C’est grâce à Louis Mizon un lieutenant de la Marine française que Muhammadu Nya, Emir de Muri a conquis les Jukun de Kona en 1892. Ainsi réussit-il à étendre l’influence de la France dans la région du fleuve Bénoué. L’Emir qui six ans auparavant avait tenté sans succès de s’emparer de Kona, en vint enfin à bout grâce aux moyens militaires et techniques mis à sa disposition par Mizon. Cela fut un événement traumatique dont on se souviendra encore à travers la tradition orale des Jukun. Cet exposé présente un texte oral recueilli en 1996, qui replace l’événement dans son contexte historique et en donne une interprétation.

Zusammenfassung

Unterstützt vom französischen Marineleutnant Louis Mizon gelang es dem Muhammadu Nya, Emir von Muri, die Jukun von Kona zu erobern. Mizon versuchte auf diesem Wege den französischen Einfluss in der Region des Benue-Flusses auszudehnen. Der Emir hatte sechs Jahre zuvor vergeblich versucht, Kona einzunehmen, aber mit Mizons überlegener Militärtechnologie wurde die Stadt nun endgültig unterworfen. Dies war ein traumatisches Ereignis, das in der oralen Tradition der Jukun bis heute erinnert wird. Der Aufsatz präsentiert einen 1996 aufgezeichneten oralen Text, der in den historischen Zusammen gestellt und erläutert ist.

|

The interference of Mizon is bitterly remembered by the Kona, who state that, but for Mizon’s guns, they would have remained independent of Fulani suzerainty. (Meek n.d., p.27) |

<1>

In the mid-nineties, the present authors collected a corpus of narratives and texts on founding histories of several Northern Jukun villages in North-Eastern Nigeria [2]. This was done in the context of an interdisciplinary project on language contact and cultural change in the West African savannahs and led to some unexpected results.

<2>

Most of the local histories given to us were texts that reflected the history of the Jukun as interpreted and told in Meek (1931). More than once, Jukun historians referred to Meek’s book or brought it along in order to make our work more convenient. Other texts, in contrast, focused on the recent past, and re-formulated (or simply created) history, referring to Jukun perspectives on ongoing conflict.

<3>

One local expert in history, Zorey Nunoye of the village of Kona, however, wanted to tell us about an aspect of the history of his village that he considered specifically important: the history of how it was destroyed and deserted, not of how it was founded. One afternoon in January 1996, Zorey Nunoye agreed to talk to Anne Storch and tell her about what he remembered of Kona history. This proved to be a most fortunate encounter, as Zorey was not only the descendant of eye-witnesses of the incident he talked about, but also closely associated to the clan who keeps some of the material evidence of history. Zorey Nunoye was not only eager to tell the story, but also wanted to prove its truth.

<4>

At the same time, he told history from beyond – not referring to those documents kept in the archives, but to the ritual and magical dimensions that lay behind the incidents of more than 100 years ago, and to the reasons why this needs to be remembered.

<5>

The text that emerged out of the encounter is not only Zorey Nunoye’s contribution, but generated a large number of comments during the process of transcribing and translating it with the help of two mother-tongue speakers of Jibe, the language of Kona [3], Edward Shaukei and John Shumen. Both were still young men in 1996, but had already been initiated to the shrines and were able to decide what to explain and what not, in order to not violate taboos and betray the ancestors and gods that resided in the shrines and sacred forests.

<6>

Consequently, the translation and commentary on the Kona text are based on comments by Shaukei and Shumen. The text presented below has several meanings, which may be commented on by generations of Kona historians to come, as the written document presented here is made available in the virtual archive.

<7>

In 1996, when the encounter and recording took place, Kona had just experienced deeply disturbing investigations against some dozens of elders who were suspected by the Nigerian police to have murdered traders of African art, who had come from Kano in order to buy sculptures in Kona, and were never seen again. Why would Zorey Nunoye tell the story of old Kona’s end and not of its recreation and recent past? Why was this incident of so much more importance to him than the village’s founding history or its recent struggle? This contribution aims at demonstrating that one important reason for his choice is that this text wants to explain that Kona men are almost invincible, and modern technology – mortars and machine guns of the police alike – do not succeed easily against these people’s knowledge on magic and spiritual agency.

<8>

Usually, an historical event is most likely to be preserved in the oral traditions of a group and transmitted when two conditions are fulfilled: the event had significance for the group at the time when it occurred and it is still significant at the time when the tradition is recorded (cf. Vansina 1985:118-19).

<9>

The episode which is the topic of the text presented in this article meets these criteria. For the Jukun of Kona it was a traumatic incident which, by drawing them into the maelstrom of the scramble for Africa, confronted them with powerful military technology unknown to them so far and subjugated this hitherto independent people.

<10>

An oral text may be regarded as an historical document which is handed over from generation to generation, being modified during this process and whose former versions are lost (cf. Vansina 1985:29). Hence it is interesting to compare the present-day tradition told by the Kona-Jukun with the description of events laid down in written form by the French adventurer Mizon and others in the late 19th century. At the end of the text, the authors’ comments on the cultural patterns and socio-religious set-up of Kona aim at providing contextual information from a late 20th century point of view.

<11>

The text is thus presented with two commentaries, after providing information on the historical set-up. One commentary is based on ethnographic and linguistic research in the 1990s and contains additional information on how the present authors interpreted the text. The second commentary is based on Edward Shaukei’s and John Shumen’s interpretation, without whom most of the recorded text would have remained incomprehensible and ambiguous to the non-Jibe audience. [4]

2. Introduction [5]

<12>

In an effort to expand the French sphere of influence in West Africa in the early 1890s, Louis Mizon, a lieutenant of the French Navy, undertook two expeditions along the Niger and Benue rivers into regions which were dominated by the British Royal Niger Company (RNC). The RNC was de facto exercising a trade monopoly, although navigation on the Niger River was nominally free to everyone (Crowder 1962:152-53).

<13>

Louis Alexandre Antoine Mizon was born in 1853 and joined the French Navy in 1869. He had accompanied Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza on his expeditions in the Congo in the early 1880s. The expeditions led by Mizon were part of a wider scheme by the French Colonial Department to gain France more influence in West Central Africa, and comprising the expeditions by Paul Crampel to Chad and by Commandant Monteil on the Upper Niger. Officially, Mizon’s expeditions were purely scientific, but the covert goals were to sign treaties with local rulers.

<14>

On his first expedition in 1890-91, after having faced various difficulties (they were attacked by the Patani on the Lower Niger and towed back to Akassa by the RNC, where several of his companions died or became so ill that they had to return) and without initial clearance by the Royal Niger Company, Mizon eventually reached Yola on the armed steam-launch ‘René Caillié’. Here he stayed for four months in the same house as Eduard Flegel had lived. [6] Zubeiru, the Emir of Yola, however, was not willing to sign a treaty with him and Mizon had to leave the capital of Adamawa by an overland route via Ngaundere. He joined De Brazza in the Congo in April 1892 before returning back to France. In his company he had S’Nabou, a 12 year-old-girl who allegedly was the daughter of a local ruler. Later it turned out that she was the niece of a Niger Company pilot and was bought as a slave. They were highly welcome guests in the salons of Paris.

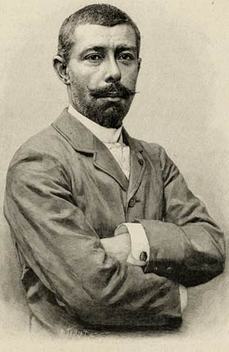

Figure 1: Louis Mizon (Alis 1894)

|

|

<15>

Notwithstanding his frustrated efforts in Adamawa, back in France he claimed to have been successful and gained support for a second expedition. This time Mizon received the permission by the RNC to travel, and in August 1892, again under the pretext of a purely commercial and scientific expedition, the two steamboats ‘Sergent-Malamine’ and ‘Mosca’, each armed with a four-pounder quick-firing cannon and carrying altogether 100 Senegalese sharpshooters, set off along the River Niger. The ships were loaded with 150 modern rifles with 18,000 rounds of ammunition and 100 revolvers with 15,000 rounds.

<16>

The RNC had attacked Jibu, a town in Muri Emirate, in 1884, 1888 and again in 1891, and consequently the Emir of Muri ordered the company to quit his territory and closed their factories at Lau and Kunini. Thus, Mizon arrived at a time suitable to his intentions. He ran his vessel aground on a sandbank, giving him a chance to stay at Muri until the next season's high water. On November 23rd, 1892 he signed a treaty with the Emir of Muri Muhammadu Nya, claiming his territory to be a protectorate of France. He established trading posts at Mainarawa and Kunini and put an end to the RNC's commerce in the emirate. Mizon gave the Emir 20 rifles and 20 revolvers and ammunition and trained his soldiers in using them, but the Emir made it clear that he required a higher price for the treaty. Mizon should assist him in conquering the Jukun of Kona which the Emir had been besieging in vain since six years. The Kona-Jukun interrupted the trade along the route coming from Kano via Bauchi, Muri and Bomanda proceeding to Bango, Tibati and Ngaundere, and even with the aid of Bauchi the Emir of Muri was unable to overpower them by his own means.

<17>

On 17th December 1892 Mizon moved with several of his companions, 14 Senegalese sharpshooters and a cannon towards the Emir’s war camp near Kona. On 25th December the attack on Kona started. The main body of troops united near a swamp with the vanguard moving the cannon. The troops of the Emir consisted of about 700 Fulani infantrymen, 120 cavalrymen, 500 allied archers and spearmen, and 20 sharpshooters with Snider rifles. Additionally there was the group of Mizon. The chief of Kona was not impressed by the gathering troops:

"Le chef de Koana n’a vraiment pas peur! Il se croit en parfaite sécurité derrière ses murs; aussi vient-il d’envoyer un défi au sultan : ‘Les blancs sont chez toi depuis cinq jours, et tu ne me les as pas encore envoyés ; il me tarde cependant de voir leur savoir-faire ! – Attend ! Dans vingt-quatre heures nous y serons, et je compte bien que tu auras fort à t’en plaindre!" (Chabredier 1894:212-213)

<18>

Kona consisted of several villages within a roughly circular arrangement of hills, and was completely surrounded by a wall and ditch. The wall was partly made of stones, partly of palisades. Mizon placed his cannon at a distance of about 270m from the wall, out of reach of Kona’s arrows. The first shots fell too short, thus the cannon was moved closer. Then the shelling cracked a breach of 2-3 m in the wall and Mizon’s Senegalese attacked through this gap, followed by the Emir’s troops. 150 inhabitants of Kona were killed or wounded, the settlement looted and ravaged, and those unable to flee – about 250 women and children – were taken as slaves. On 28th December, Inu, the chief of the Kona, who had fled to the surrounding hills, brought in his submission. About 2,000 Kona-Jukun who returned because of lack of food were also enslaved. Mizon was offered a pick of slaves by the Emir and he choose two young girls for his Arab lieutenant Hamed and an eight-year-old girl for his attendant S’Nabou.

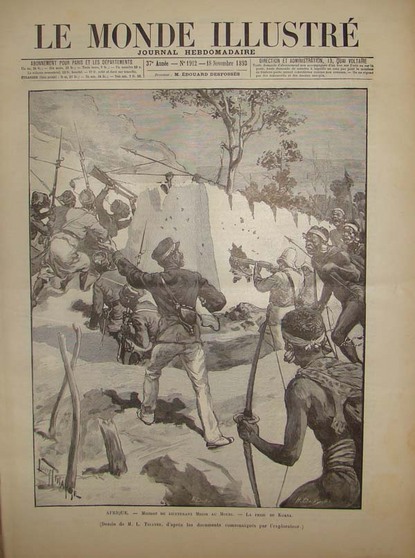

Figure 2: Mizon attacks Kona (Le Monde illustré, 18. Nov. 1893)

|

|

<19>

In mid-May 1893 Mizon again helped the Emir of Muri with a force under the command of Adjutant Chabredier to subjugate the inhabitants of Dulti who were accused of obstructing trade routes (Alis 1894:489, Chabredier 1894:243, 258-259).

<20>

The surgeon of the expedition Dr. Henri Ward had returned to Europe shortly after the Kona massacre and, in an effort to dissociate himself from Mizon’s villainous behaviour, published an account in the radical newspaper L’Intransigeant. His story was later corroborated by other members of the expedition, namely Henri Vaughn and Albert Nebout.

<21>

Mizon was recalled to France. However, he did not obey, assuming the order was a forgery by the RNC, but instead proceeded to Yola in July 1893 to negotiate a treaty with the Emir Zubeir. He offered the Emir rifles, revolvers and two cannons. William Wallace, acting Agent General of the RNC, also arrived at Yola after having seized and burnt the French trading posts at Mainarawa and Kunini. The tension between the rival French and British parties was eventually resolved when the Emir recognised the superior strength of the RNC and Mizon’s weak position who acted without backing from his government. On 22nd September 1893 Mizon left Yola on board of his ship for the last time. He dropped S’Nabou at the Catholic mission at Onitsha where she gave birth to a boy of light complexion.

<22>

In French popular periodicals, such as Le Monde Illustrè (1893), Le Journal des Voyages - Aventures de Terre et de Mer (1892-1894), Le Tour du Monde (1892) and Le Petit Journal (1892), Mizon was depicted as a colonial hero and apologetic and profusely illustrated accounts of his expeditions were published. [7]

<23>

In 1895 Mizon became Resident of Majunga in Madagascar, and four years later he was nominated governor of Djibouti but died before reaching his post, probably through suicide, on March 23, 1899.

<24>

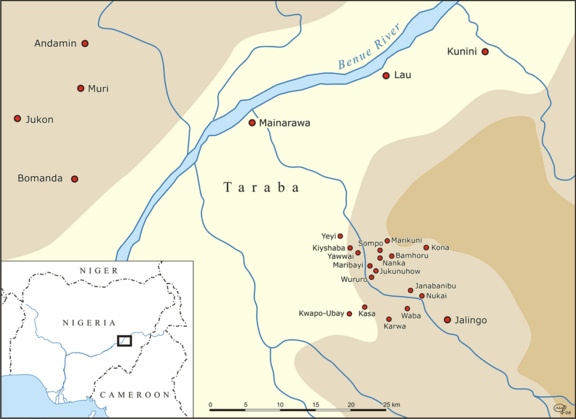

Kona is a settlement approximately 10km to the northwest of Jalingo, the capital and administrative center of Taraba State, Nigeria.

Map: Kona and the Jibe area

|

|

Historically Kona is on the northern fringe of what was once a vast Jukun confederacy. In contrast to other Jukun-speaking commmunities to the north and west (for a full account cf. Storch 1999), the people of Kona or Jibe [Ʒí b ə́], as they call themselves, claim to still retain many religious and socio-cultural features of the pre-colonial past. An important property of Jibe identity is that even though most people of Kona and surrounding hamlets have now become Christians and members of the Catholic Church, the local mam-religion [8] still plays an important role in both daily life activities and in passage rites.

<25>

The mam-religion had been an important factor in establishing and maintaining power relationships in the pre-colonial Kororofa empire (Meek 1931, Webster 1994, Storch in print) and was closely associated to divine kingship. Prior to its destruction and to subsequent massive effort by missionaries in the 1930s, Kona was ruled by a divine king, as were most Jukun communities. Jukun divine kings, such as the aku of Wukari, or the kùrù of Kona, are attributed to have more spiritual power than a normal person and as such are believed to constantly exist as augmented subjects, embodying moon, sun, gods, and ancestors. Hence, local history – such as the document dealt with in the present contribution, where loss of power and of control over local resources are described –, needs to interpret crisis and collapse in the context of the divine king’s agency and the violation of taboos that contributed to reduce his spiritual powers.

<26>

But the violation of taboos also plays an important role in the context of how group boundaries are defined, and how the “other” can gain such power that magic and godly chieftaincy do not provide sufficient protection any longer. Kona, as most Jukun societies, is strictly exogamous. Women are normaly married from either other clans or other groups altogether. While male members of the society had and have access to the shrines and participate in religious activities of the mam-cult, women were and are largely excluded from almost all religious activities, with the exception of being allowed to offer food and beer to the gods and ancestors (Dinslage & Storch 2000a & b). At the same time, male control over religious resources and power is symbolized and enforced by a number of taboos that concern all male bodily effluvia, male sexual organs and substances of a slimy viscosity that are considered both powerful and dangerous.

<27>

In modern Kona, food habits, popular story telling, as well as every-day communication patterns very much reflect this situation. Moreover, even though women now do have access to religion via the Catholic Church, situations of crisis and tension of the past years very often included a renaissance of practices of local religions such as mam. In the local account of a late 19th century globalization event that is dealt with here, it is not women’s interference into the men’s religious duties, or lack of agency of the current king, but the appearance of the “ultimate other”, that finally causes the complete destruction of the village and the subsequent enslavement of many of its inhabitants. Mizon was not only one of the first Europeans whom the Jibe ever met, but also the person who bringing modern military technology and steam energy into the area. This experience is reformulated in describing Mizon as an abstract symbolisation of otherness.

<28>

The text also illustrates how the relocalization of socio-religious concepts and history is conceptualized among Jibe. In local history, Kona is constantly re-invented as a place where almost every part of life is based on magic and the observation of taboos. Whatever happens to a person is attributed to the agency of spirits and ancestors, whereby magic plays a key-role in understanding such activities as hunting and warfare, but also politics and conflicts between contemporary groups.

<29>

Moreover, the shrines that are forbidden for women and all non-initiated persons, are still existing as an important source of power for the men. That the beliefs and secrecy surrounding them are threatening enough to outsiders of the cult to let the community retain its independence from the nearby Muslim centre of Jalingo, is illustrated by local history that deals with the more recent past (Storch & Dinslage 2000b:225 ff.). In the 1990s, attempts to sell off religious mam-objects and to take photographs inside some of the shrines led to the disappearance of at least two traders of African art and the subsequent imprisoning of a large number of men from Kona. It is interesting to note that in oral accounts of this incident patterns of local history are used that can also be found in accounts dealing with earlier confrontations between members of the mam cult and Western outsiders, and in the text relating to Mizon presented here.

<30>

In such accounts on violation of taboos and threat of losing control over spiritual and magic powers, Jibe historians very often emphasize that Kona society does not accept any other explanation for disease or death but magic. This holds also true for other disruptive or exceptional incidences. Thus the raid on and subsequent shelling of Kona by Mizon and the Emir of Muri has become a crucial issue in local historiography. While it is a common feature among other Jukun communities to focus oral tradition on an early migration from Yemen or Egypt, fitting themselves in the widespread pattern of the Kisra legend (cf. Stevens 1975), the Jibe hardly mention this topic at all. For the Jibe “real history” starts when the group migrates from a former settlement place on the bank of the River Benue. This place is referred to as kúrò (‘place of death’) and is known to be a ghost-haunted, lonely open space where the spirits of the ancestors live. From there the Jibe moved to where they live today. As a reason for that migration usually a quarrel over chieftancy is given.

<31>

The absence of accounts on earlier migration history and of mythological texts has been interpreted as the result of massive cultural change during the 19th century (Meek 1931), which resulted out of genocidal slave-raiding, jihadist attacks, etc. This suggests that the text discussed in the present contribution also reflects collective trauma and uses magic and spirit possession practices as media of dealing with it. Hence, even though the lists of kings and the major stations of their history are still commonly memorized and reproduced, the Jibe are more conscious of the bombardments of Kona by Mizon than of any other chapter of their history. The defeat and destruction of Kona and the use of formerly unknown modern weaponry had such an impact on the community’s collective memory that even today this topic is constantly discussed when elders tell younger generations about their history, discuss their common heritage and so forth.

<32>

The strong emphasis which is laid on the incident consequently is fostered by the significance attributed to magic in Kona, a significance which persists even today despite the influences of Christianization and Islamization. Jibe oral historiography rejects all other explanations for the defeat and subjugation of the village apart from internal conflicts which are believed to have counteracted and weakened their magic forces. Thus, the “ultimate other”, Mizon and his war machinery, is not a truly powerful or dangerous figure as far as the story’s sub-text is concerned. For generations Kona was known to be invincible – there was the huge fortification wall built around the town, and as the Jibe were so famous for their knowledge and mastery of magic, they had not been seriously attacked. It was not until the Fulçe attacked them with the assistance by Europeans that Kona was defeated and the wall finally destroyed. This was so in opposition to anything experienced in “invincible” Kona before that the only means of explaining and understanding the incident was interpreting it as a result of magic practiced by a competing Jibe chief. Without internal conflict and Jibe performing witchcraft against the ruling chief, Mizon might never have had a chance to destroy Kona. Mortars would have not done any harm.

<33>

After the destruction of Kona and its wall those Jibe who were not caught and enslaved fled into the surrounding bush; some of them eventually settled north of the Benue (in Jukon and Andamin), but most of them returned after a while and rebuilt the town. The ruins of the fortification wall are still visible today, but its presence is felt more in the common name by which Kona is locally known, i.e. gàrù (‘wall’ in Hausa). The official name Kona, however, is mostly used by strangers and in administrative contexts; it may by etymologically related to the ethnonym Hõne, which refers to the Northern Jukunoid neighbours of the Jibe, and to Gwana, an old political and cultural centre of that community. Another possible etymology of Kona might be the formula used in Jibe when entering a compound or a village: káwù na ‘stay [at the] compound’.

<34>

The modern layout of the town is not very much different from what is described in the oral text: Kona is divided into several quarters which are the homes of the different clans (cf. Dinslage & Storch 2000b). Strangers, either from other ethnic groups or foreigners such as European missionaries, are not allowed to settle inside the town. There is a mission station run by Catholic sisters at the outskirts of Kona. The remains of the mortars and other historical artifacts are kept in the chief’s palace and in the shrines. They form an important part of the community’s heritage and contribute to a common cultural identity that allows even younger Jibe to distinguish themselves in a modern multi-ethnic urban environment such as the nearby state capital Jalingo.

<35>

The oral text presented below consists of a description of the attack and of the magical practices involved. In outline it describes the same actions as the European sources do, albeit from the point of view of the Jibe. The text was recorded in January 1996 in Kona, were it was told by Zorei Nunoye (approximately 60-70 years old) to a large audience. It was translated with the assistance of John Shumen (c. 30 years) and Barnabas Vakkai (c. 60 years).

-

They migrated from Kuro (lit.: ‘place of death’), they came from Kuro to settle here at the ruined town, place of baobabs. As they left Kuro, they came to settle here at the ruined town, place of baobabs, they passed there and came to stay here.

-

War, war came up upon them. One man, Buba, came to the place where the people now settled, and that place was not hidden. There was no secret. He said: ‘The people should come! If you stayed there far away and have the hills around you, one can say it is like in a stomach, you live like in a covered, sheltered place.’ So they came to settle here.

-

Agauwa then came and entered the place here, and there was war constantly. If there is no weapon, with what can you defend yourself? Well, that is why they tried and built the wall. It goes up to the mountain, it climbs the mountain. Again, many people came and they divided everything, even the places where they stayed. These are the parts of the wall which they used to break. If one sees that a person comes, everything is divided and the wall is rebuilt close to their homes. Many people settled there. They feared for their lives and difficulties overwhelmed them. So they built a wall because misfortune had met them. Don’t they like their lives? They built a wall because they should cover and protect the gates at the quarters of the Bajibero, the Badoni and the Kawdad. Each and every clan had its own part of the wall, which they had to repair when it was damaged. They went there to stay, and when war came nothing could have defeated them; they just stayed there.

-

Then they went around for the question of chiefdom. Oh, we suffered from that competition for chiefdom! They betrayed each other and then bombarded these things, the wall there. When they bombarded it, water came out of the ground and down from above, so they were not conquered. When they [the Fulçe] took their guns and focussed them at the wall, a wind came and pushed the guns around to the reverse. They said: ‘No! What town is here? It is a powerful town!’ Ba of the clan Banojiri wanted to succeed the chief Inu Janu and to become a king. Inu Janu is the father of Kamiy and the grandfather of Kuku Dãw. Ba wanted to be the king, so he invited the people to come.

-

Ba wanted to become a king and came and invited people. They came on foot. They came and did an effort until they got tired and returned. He said: ‘What? What again is this? Is there anybody else in this town whom it may belong to but me? The town belongs to our grandfather and father!’

-

Just a small bottle-gourd, just a small bottle-gourd. Ba took the skin of a ratel [mellivora capensis] and put the gourd on its back, shouted some secret words and called citations. He took the bottle-gourd and poured water out of it. He poured it down and destroyed the secret of the town. They then returned and destroyed the wall. They destroyed the wall and killed Numtayi of the Bawuro. Numtayi slept at the gate of the wall, so that nothing could enter. The wall fell on him. The wall went down, as big as this. The wall fell on him and took him down.

-

Ba then waged war, he was leading the warriors [for the Fulçe], and as they fought, a swallow came. The swallow threw magic things at the people who shot at the Jibe. That was something of the olden days, they say it was a blessing. The swallow was sent to bless us. Fighting changed as the blessing was sent.

-

Numtayi took a spear and came out to stab the first man who fell down. After this, the wall fell. As it fell on him, it spared his left hand but covered him up to his waist. There was no chance left for him. A European came and shot him and said: ‘They should go and let everybody see the person who sits at the gate of the wall, so that nobody could conquer the Jibe.’ He climbed very fast and came to the wall, but Numtayi took one spear and shot him dead. Another one then followed the first one. He said: ‘What? Let me see what happened to my senior brother!’ Again – very fast – here where the remains of the wall fell, the man came climbing and Numtayi took a spear and shot him. Numtayi shot two people. Others came, and as his spears were finished, they found him and killed him, cut his head off and left, leaving the remains like that. The next day the Europeans came to cut off the heads and left.

-

The king of the Bachama saw this. Someone was there at the banks of a nearby stream and witnessed the fight, and he went to the king and said: ‘Leader, the complete town is destroyed. Let the women run, let them go, because the Jibe settle nearby and their wall is broken from here up to the end. Fire eats everything in the land.’ The women flew and went to the mountains.

-

King Inu of Kona sat on a stone, there at the palace. Your grandfather Vani was not yet initiated. Vani came and said: ‘Chief, why do you still sit here? The town is clompletely destroyed, the wall broke and Numtayi is lost and not alive anymore.’ Inu said, that a chief who is so big cannot run away from fire. If death comes, that is that. Vani said, he should get up. Your grandfather Vani! He said, he should get up. The chief said, he could not get up, no way. – He should rise! He must! – No, he cannot rise any more! Vani lifted him and carried him with his arms. A youth! This was a youth in those days – so big. Yes! He took him on his shoulders, and there he went.

-

Ba now came home and prepared the ritual beer for the spirits and ancestors. The spirits just were with the age-mates of Vani, who were undergoing their initiation ceremonies. Ba said: ‘Son!’, Vani answered. ‘You have not seen the spirits?’ Vani said, no. They gave him blessings and went out together. Ba took Vani out himself and prepared a different beer for the spirits. Vani now stayed with his age-mates to be initiated, and there he saw the spirits and ancestors. Your grandfather Vani was there at the secret place after they destroyed our town.

-

That is why it was ruined: because of the question of chieftaincy. Yes. If the children of the chief were like Vani, nothing ever defeated us. You see how we are. If something overwhelms us somehow – at wartime we unite again. We came a long way since our migration from Kuro, but we don’t fear war. Yes. This is our gift. [...]

-

That is what destroyed and scattered us in war. That is what came and defeated us. We found the bombshells like this, two of them are here at the quarter of Wururo. The people of Wururo found them. We found them as they are now. If you say I may go I will bring them. She should come and see, yes. That’s how it is, no? Yes, this is what came to destroy our wall. I will go to the place of the Wuru, I myself. A child of the Bachama – Dabang – is the one who found one. I myself found one. We found them during the reign of King Shumen. King Dãw came and said he should see them, so one was given to him. One other is at our place here. The thing that destroyed our wall. I go and bring it. Let her come and see them. The Europeans then stayed on. You know, they knew better! I shall go soon.

3.3. Transcribed text [9]

|

bə-dòg |

há̰ |

àbo |

kú-rò |

bə-dòg |

kú-rò |

|

they-stand_up |

as |

at |

priest-LOC |

they-stand_up |

priest-LOC |

|

ǹ-bìy |

shí |

àré |

kání |

nòw |

be |

ágbání |

kəd |

rí |

yéy |

shí |

|

CONS-come |

sit |

there |

ruin |

house |

place |

baobab |

grow |

FOC |

there |

sit |

|

ábə-dòg |

à |

kú-rò |

bək-bìy |

shí |

àré |

à |

|

as_they-stand_up |

PREP |

priest-LOC |

they_REF-come |

sit |

there |

PREP |

|

kání |

nòw |

be |

ágbání |

àkíy |

rí |

ǹ-wàm |

àré |

ya |

sə́d |

se |

|

ruin |

house |

place |

baobab |

here |

FOC |

CONS-pass |

there |

go |

stand |

there |

|

kànì |

kànì |

bìy |

ǹ-dòg |

ho-bà |

|

war |

war |

come |

CONS-stand_up |

collect-them |

|

ŋwunò |

zṵ̀ŋ |

bùbà |

yì-bìy |

ŋwî |

be |

àbá |

yì-shì |

há̰ |

|

man |

one |

Buba |

CONT-come |

saying |

place |

that_they |

CONT-sit |

as |

|

ŋwî |

be |

ke |

há̰ |

ŋwî |

kə̀g |

mə̀ŋ |

àsírí |

bú-àyéy |

mə̀ŋ |

|

saying |

place |

here |

as |

saying |

hide |

NEG |

secret |

thing-there |

NEG |

|

ŋwî |

àbá |

yì-bìy |

fá |

há̰ |

má-sə́d |

bo |

nón |

nón |

néy |

|

saying |

that_they |

CONT-come |

then |

as |

COND-stand |

there |

far |

far |

like |

|

má-wéy |

kùnì |

há̰ |

a-yì |

gòg |

àzà̰ŋ |

bə-yì |

ǹ-sə́d |

|

COND-see |

hill |

as |

you-say |

gather |

together |

they-say |

CONS-stand |

|

dò̰ |

fúní |

ŋwî |

be |

a-rí-gag |

à |

kay |

ŋwî |

àbá |

yì-bìy |

shí |

ke |

|

like |

stomach |

saying |

place |

you-FUT-cover |

PREP |

home |

saying |

that_they |

CONT-come |

sit |

here |

|

ágàuwã |

yì-bìy |

kàd |

rí |

ke |

be |

à |

ke |

há̰ |

|

Agauwa |

CONT-come |

enter |

FOC |

here |

place |

PREP |

here |

as |

|

ǹ-bìy |

kad |

há̰ |

də̀rì |

kànì |

há̰ |

|

CONS-come |

enter |

as |

body |

war |

as |

|

bú-tár-nú |

má-bámə̀ŋ |

a-wúb |

bə́ |

kê |

|

thing-shoot-mouth |

COND-not_there |

you-defend |

with |

what |

|

tò |

ŋwà |

àke |

sa |

rí |

bə-yì-sa |

kókàrí |

bə-mì |

gàrù |

|

well |

he |

that |

do |

FOC |

they-CONT-do |

endeavour |

they-build |

wall |

|

rí |

ya |

kán |

à |

kùnì |

ǹ-ye |

nán |

à |

kùnì |

ǹ-ye |

nán |

há̰ |

|

FOC |

go |

up |

PREP |

hill |

CONS-go |

climb |

PREP |

hill |

CONS-go |

climb |

as |

|

m̀pə̀r |

bìy |

nanə́k |

bə-kà̰ŋ |

bə-kyàb |

báyì |

rí |

be |

sə́d |

shí |

|

person |

come |

many |

they-repeat |

they-divide |

all |

FOC |

place |

stay |

sit |

|

dí |

rí |

be |

à |

gàrù |

kyàg |

yéy |

sə́d |

shí |

|

that |

FOC |

place |

PREP |

wall |

crack |

there |

stay |

sit |

|

má-nə́ŋ-wéy |

nə́m |

m̀pə̀r |

bìy |

nanə́k |

bə-kà̰ŋ |

kyàb |

|

COND-you-see |

that |

person |

come |

many |

they-repeat |

break |

|

ǹ-kà̰ŋ |

mì |

sób |

à |

yay |

m̀pə̀r |

àshí |

à |

yay |

mòn |

à |

yéy |

|

CONS-repeat |

build |

extend |

PREP |

home |

person |

sitting |

PREP |

home |

be_much |

PREP |

there |

|

bə-zə́n |

áŋwunu |

wàhálà |

kàb-bè |

rí |

|

they-fear |

life |

problem |

overwhelm-them |

FOC |

|

ábə-mì |

gàrù |

rí |

wàhálà |

də̀g-bè |

na |

néy |

bə-zə̀m |

áŋwunu |

|

that_they-build |

wall |

FOC |

problem |

find-them |

lie |

how |

they-like |

life |

|

bə-mì |

gàrù |

rí |

jírí |

àŋwá-rí-gàg |

bə́ |

gàg |

à |

ke |

|

they-build |

wall |

FOC |

matter |

they-FUT-cover |

and |

cover |

PREP |

here |

|

nú |

yínù |

bú |

bá-jíbə́-rò |

bú |

bá-donì |

bə́ |

káwdad |

|

mouth |

road |

thing |

people-Jibe-LOC |

thing |

people-Doni |

and |

Kawdad |

|

nú |

pyínù-wà |

sí-yéy |

sí-yéy |

sí-yéy |

márì |

bá-kò̰ |

bú-bə̀ |

|

mouth |

road-your |

stay-there |

stay-there |

stay-there |

group |

people-any |

thing-their |

|

má-zad |

bə-rí-wòɣ |

à |

rí |

|

COND-wash_away |

they-FUT-plaster |

PREP |

FOC |

|

bə-rí-ya |

rí |

bə-bìy |

sí-yéy |

sə́d |

sə́d |

àhá̰ |

kànì |

|

they-FUT-go |

FOC |

they-come |

stay-there |

stay |

stay |

as |

war |

|

má-bìy |

bú-zṵ̀ŋ |

a-rí-jì-bà |

jì-bà |

mə̀ŋ |

bə-sí-yéy |

sə́d |

sə́d |

|

COND-come |

thing-one |

it-FUT-eat-them |

eat-them |

NEG |

they-stay-there |

stay |

stay |

|

də̀rì |

də̀rí |

bə̀ŋ |

ke |

rí |

jírí |

kùrù |

|

body |

body |

go_round |

for |

FOC |

matter |

king |

|

yi-hò |

rə̀g |

nád |

bə́-wà |

nə́m |

jírí |

kùrù |

sə́ŋímà |

|

we-take |

PERFVE |

suffer |

with-it |

like_that |

matter |

chief |

alas |

|

bə-ya |

dàd |

rí |

rí-bìy |

tàt |

bú |

à |

rí |

gàrù |

sə́d |

shí |

|

they-go |

betray |

FOC |

FUT-come |

bomb |

thing |

PREP |

FOC |

wall |

stay |

sit |

|

bə-má-tàt |

bú |

za-pə̀r |

zu |

à |

bó |

|

|

they-COND-bomb |

thing |

liquid-water |

come_out |

PREP |

place_to |

|

hwáí |

ǹ-rí-zu |

à |

ke |

vúrí |

jì |

m``ə̀ŋ |

|

upside |

CONS-IMPFVE-come_out |

PREP |

here |

soil |

eat |

NEG |

|

bə-má-fád |

nú |

pyírù |

rí |

má-zə̀g |

sòg |

à |

bó |

|

they-COND-turn |

mouth |

fire |

FOC |

COND-take |

put |

PREP |

place_to |

|

gàrù |

wòw |

zu |

à |

bó |

ǹ-biy |

dàb |

zə̀g |

nú |

|

wall |

wind |

come_out |

PREP |

LOC |

CONS-come |

push |

take |

mouth |

|

pyírù |

zə̀g |

kà̰ŋ-bà |

yákə̀n |

|

fire |

take |

reverse-them |

back |

|

bə-yì |

ʔàʔà |

àsé |

lòw |

ke |

há̰ |

lòw |

àhwáy |

hwáyì |

rí |

|

they-say |

no |

what |

house |

here |

as |

house |

being_powerful |

big |

FOC |

|

bâ |

bà-nójìrì |

sə̀ŋ |

kùrù |

à |

be |

ìnujànù |

rí |

|

Ba |

people-Nojiri |

want |

king |

PREP |

place |

Inujanu |

FOC |

|

ìnujànù |

shà |

bə́ |

kàmìy |

kùkú |

dãw |

h1á̰ |

|

Inujanu |

father |

with |

Kamiy |

grandfather |

Dãw |

as |

|

bâ |

sə̀ŋ |

na |

kùrù |

ǹ-ya |

dad |

m̀pə̀r |

bìy |

àré |

|

Ba |

want |

lie |

king |

CONS-go |

invite |

person |

come |

there |

|

bà-nójìrì |

sə̀ŋ |

kùrù |

ke |

rí |

ǹ-bìy |

dad |

m̀pə̀r |

|

people-Nojiri |

want |

king |

here |

FOC |

CONS-come |

invite |

person |

|

bə-bìy |

kyén |

kyén |

bə-bìy |

sa |

sa |

ní |

ǹ-kà̰ŋ |

àré |

|

they-come |

walk |

walk |

they-come |

do |

do |

tire |

CONS-reverse |

there |

|

ku-yì |

ʔaʔa |

ŋwî |

màŋ |

də̀rì |

káyì |

ré |

ŋwî |

lòw |

ke |

lòw |

|

he-say |

no |

saying |

but |

body |

what |

again |

saying |

house |

here |

house |

|

m̀pə̀r |

zṵ̀ŋ |

ré |

ŋwî |

lòw |

bâ |

lòw |

bú |

kùkú |

lòw |

bú |

shà |

|

person |

one |

there |

saying |

house |

thing-of |

house |

thing |

grandfather |

house |

thing |

father |

|

àŋwu |

ákùnì |

nə́m |

àŋwu |

ákùnì |

nə́m |

|

small |

bottle_gourd |

like_that |

small |

bottle_gourd |

like_that |

|

ku-dàd |

zə̀g |

hwów |

tání |

ǹ-zə̀g |

sòg |

à |

ke |

yákə̀nù |

ŋwàyì |

|

he-take |

take |

skin |

ratel |

CONS-take |

put |

PREP |

here |

back |

its |

|

zə̀g |

léy |

jìnì |

ǹ-zə̀g |

léy |

jìnì |

|

take |

voice |

speech |

CONS-take |

voice |

speech |

|

ku-z`ə̀g |

rə̀g |

wúr |

jìní |

za-pə̀r |

zu |

à |

ke |

|

he-take |

PERFVE |

pour |

down |

liquid-water |

come_out |

PREP |

here |

|

ku-zu |

wúr |

jìní |

ku-zə̀g |

lòw |

gbán |

rə̀k |

|

he-come_out |

pour |

down |

he-take |

house |

kill |

PERFVE |

|

bə-bìy |

kà̰ŋ |

àré |

ǹ-yag |

gbán |

gàrù |

rí |

|

they-come |

reverse |

there |

CONS-go |

destroy |

wall |

FOC |

|

bə-gbán |

gàrù |

há̰ |

ǹ-gbán |

há̰ |

númtàyì |

bá-wúró |

ke |

|

they-destroy |

wall |

as |

CONS-destroy |

as |

Numtayi |

people-Wuro |

here |

|

a-na |

nú |

gàrù |

rə̀g |

bú-zṵ̀ŋ |

àkàd |

zə̀g |

mə̀ŋ |

gàrù |

hùm-kù |

àhá̰ |

|

he-lie |

mouth |

wall |

PERFVE |

thing-one |

entering |

take |

NEG |

wall |

fall-him |

as |

|

gàrù |

zə̀g |

ye |

hùm |

à |

jìní |

gàrù |

na |

àhwówà |

nə́m |

|

wall |

take |

go |

fall |

PREP |

down |

wall |

lie |

size |

like_that |

|

gàrù |

hùm-kù |

ǹ-zə̀g-kù |

ye |

hùm |

à |

jìní |

há̰ |

na |

|

wall |

fall-him |

CONS-take-him |

go |

fall |

PREP |

down |

as |

lie |

|

bâ |

ku-yì-nóŋ |

kànì |

ǹ-nóŋ |

nóŋ |

há̰ |

ǹ-nóŋ |

nóŋ |

há̰ |

|

Ba |

he-CONT-lead |

war |

CONS-lead |

lead |

as |

CONS-lead |

lead |

as |

|

yì-bìy |

àhwáì-na-pyínù |

àhwáì-na-pyínù |

yì-bìy |

ŋwùn |

dàd |

zə̀g |

m̀pə̀r |

tàt |

rí |

há̰ |

|

CONT-come |

sky-lie-road |

sky-lie-road |

CONT-come |

throw |

take |

take |

person |

shoot |

FOC |

as |

|

àbá |

nə̀rí |

bə-yì |

márì |

márì |

na |

|

thing_that |

olden_days |

they-say |

blessing |

blessing |

lie |

|

àhwáì-na-pyínù |

há̰ |

bək-som-kù |

somì |

bək-már-yì |

néy |

|

sky-lie-road |

as |

they_REF-send-him |

sending |

they_REF-bless-us |

now |

|

bək-kà̰ŋ |

bú |

kà̰ŋ |

àhá |

àsom-kù |

som |

bə́ |

márì |

|

they_REF-reverse |

thing |

reverse |

like |

sending-him |

send |

with |

blessing |

|

númtàyì |

zə̀g |

sáw |

sòg-kù |

vàk |

bìy |

ku-bìy |

ŋwùn |

|

Numtayi |

take |

spear |

put-him |

palm_of_hand |

come |

he-come |

throw |

|

zə̀g |

m̀pə̀r |

zə̀g |

tar |

jìní |

ke |

be |

há̰ |

yì |

mə́n |

rí-pyìnì |

|

take |

person |

take |

shoot |

down |

here |

place |

as |

CONT |

then |

IMPFVE-first |

|

tò |

yákə̀n-wà |

há̰ |

gàrù |

húm |

nə́m |

à |

ke |

|

well |

back-his |

as |

wall |

fall |

like_that |

PREP |

here |

|

gàrù |

húm-kù |

há̰ |

ǹ-fám-kù |

vó-m̀ |

jìù |

ǹ-húm-kù |

ke |

sə́n |

|

wall |

fall-him |

as |

CONS-leave-him |

hand-his |

eating |

CONS-fall-him |

here |

waist |

|

dámá |

dan |

bà |

də̀rì |

yéy |

mə̀ŋ |

kà̰ |

|

unpossible |

be_not |

no |

body |

there |

NEG |

now |

|

bàturè |

bə-bìy |

tat |

bú |

há̰ |

ŋwî |

bək-ya |

àré |

|

European |

they-come |

shoot |

thing |

as |

saying |

they_REF-go |

there |

|

ábə-wéy |

dí |

m̀pə̀r |

ke |

ábə-yì-wà |

shí |

rí |

nú |

|

that_they-see |

DEF |

person |

here |

that_they-know-him |

sit |

FOC |

mouth |

|

gàrù |

bú-zṵ̀ŋ |

kàd |

zə̀g |

jíbə́ |

mə̀ŋ |

há̰ |

|

wall |

thing-one |

enter |

take |

Jibe |

NEG |

as |

|

ku-ŋə́n |

nə́m |

kórì |

kórì |

kórì |

ŋwî |

áku-bìy |

nán |

há̰ |

à |

|

he-climb |

like_that |

fast |

fast |

fast |

saying |

that_he-come |

ascend |

as |

PREP |

|

ke |

gàrù |

nə́m |

ku-dàd |

zə̀g |

sáw |

zṵ̀ŋ |

ǹ-sòg-wà |

zə̀g |

ya |

tàt |

rə̀g |

ke |

|

here |

wall |

like_that |

he-take |

take |

spear |

one |

CONS-shoot-it |

take |

go |

shoot |

PERFVE |

here |

|

nyen |

ku-yì-ná-kù |

à |

yákə̀n |

há̰ |

ŋwî |

hḿ |

ǹ-ye |

|

outside |

he-CONT-follow-him |

PREP |

back |

as |

saying |

what |

CONS-go |

|

rí |

ǹ-wéy |

bâ |

àsa |

dá-m̀ |

há̰ |

|

FOC |

CONS-see |

thing_that |

doing |

senior_relative-my |

as |

|

ǹ-kà̰ŋ |

kórì |

kórì |

à |

ke |

àkə̀má |

gàrù |

bə-húm |

há̰ |

|

|

CONS-reverse |

fast |

fast |

PREP |

here |

remains |

wall |

they-fall |

as |

|

ǹ-kà̰ŋ |

yì |

áku-bìy |

ŋən |

nə́m |

há̰ |

ku-kà̰ŋ |

zə̀g |

|

CONS-reverse |

CONT |

that_he-come |

climb |

like_that |

as |

he-reverse |

take |

|

sáw |

rə̀g |

ǹ-sòg-wà |

yì |

há̰ |

ku-zə̀g |

bìy |

tàt |

m̀pə̀r |

pyénà |

|

spear |

PERFVE |

CONS-shoot-him |

CONT |

as |

he-take |

come |

shoot |

person |

two |

|

bək-bìy |

sáw |

və́n |

fòm-kù |

rə̀g |

sáw |

və́n |

fòm-kù |

|

the_REF-come |

spear |

finish |

leave-him |

PERFVE |

spear |

finish |

leave-him |

|

rə̀g |

bək-pì-yag |

ǹ-ye |

də́g-kù |

ǹ-gbán-kù |

|

PERFVE |

they_REF-then-go |

CONS-go |

meet-him |

CONS-kill-him |

|

ǹ-kàm |

zə̀g |

kíní |

ye |

yag |

rí |

ǹ-fòm |

ábə̀kə̀ |

àhá̰ |

|

CONS-cut |

take |

head |

go |

go |

FOC |

CONS-leave |

rest |

like_this |

|

àkíy |

ná̰wù |

bàturè |

bə̀ |

à |

ke |

bìy |

bə̀k-kə̀m |

zə̀g |

kíní |

ye |

|

tomorrow |

day |

European |

they |

PREP |

here |

come |

they_REF-cut |

take |

head |

go |

|

yag |

rí |

ǹ-fòm |

ábə̀kə̀ |

àhá̰ |

kùrù |

kə́ŋbá |

wéy |

|

go |

FOK |

CONS-leave |

rest |

like_this |

king |

Bachama |

see |

|

ku-yì-shí |

há̰ |

àré |

nú |

za-pə̀r |

wúnkə̀rè |

fé |

ku-dòg |

|

he-CONT-sit |

as |

there |

mouth |

liquid-water |

Wunkere |

and |

he-rise |

|

ǹ-ye |

kàd |

bo |

kay |

ŋwî |

áy |

ánóŋə̀ |

nòw |

báyì |

báyì |

rí |

|

CONS-go |

enter |

place_to |

home |

saying |

oh |

leader |

house |

complete |

complete |

FOC |

|

ábə |

wurwà |

shár |

ábə -ya |

néyì |

ku-shí |

zu |

zu |

ke |

|

that_they |

woman |

run |

that_they_go |

because |

he-sit |

near |

near |

here |

|

gàrù |

gbàn |

rí |

há̰ |

hár |

sə́d |

sə́d |

ya |

rə̀k |

pyírù |

jì |

ke |

ávə́rí |

rə̀g |

|

wall |

destroy |

FOC |

as |

until |

stay |

stay |

go |

PERFVE |

fire |

eat |

here |

land |

PERFVE |

|

sə́dne |

tò |

bá-wurwà |

bìk |

ǹ-ye |

yag |

rə̀g |

ágàw |

kùnì |

|

anyhow |

well |

people-woman |

break_away |

CONS-go |

go |

PERFVE |

side |

hill |

|

kùrù |

ìnu |

ku-dòg |

ǹ-ye |

zu |

shí |

à |

ke |

ǹ-zu |

|

king |

Inu |

he-rise |

CONS-go |

come_out |

sit |

PREP |

here |

CONS-come_out |

|

shí |

à |

ke |

àbani |

ke |

fadà |

ǹ-shí |

|

sit |

PREP |

here |

stone |

here |

palace |

CONS-sit |

|

kùkú |

nâ |

há̰ |

vánì |

mə́n |

wéy |

jánu |

mə̀ŋ |

|

grandfather |

this_yours |

as |

Vani |

touch |

see |

ancestor_mask |

NEG |

|

vánì |

sə́d |

bo |

ǹ-bìy |

ŋwî |

ánóŋə̀ |

a-shí |

rə̀g |

sə́d |

káyì |

há |

|

Vani |

stay |

place_to |

CONS-come |

saying |

leader |

you-sit |

PERFVE |

sit |

what |

INTERR |

|

ŋwî |

na |

nòw |

báyì |

rə̀g |

ŋwî |

gàrù |

gbàn |

rə̀g |

|

saying |

lie |

house |

complete |

PERFVE |

saying |

wall |

destroy |

PERFVE |

|

númtàyì |

ján |

bá |

àsóni |

mə̀ŋ |

ku-yì |

ŋwî |

áhwòw |

há̰ |

kùrù |

shád |

pyírù |

shád |

ré |

|

Numtayi |

lose |

NEG |

life |

NEG |

he-say |

saying |

bigness |

as |

king |

run |

fire |

run |

INTERR |

|

kìy |

má-bìy |

rə̀g |

shí-kè-náŋ |

|

death |

COND-come |

PERFVE |

that-is-it |

|

ku-yì |

àŋwà-dòg |

də̀rì |

vánì |

kùkú-nə̀ŋ |

ku-yì |

àŋwà-dòg |

|

he-say |

he_SUBJ-rise |

body |

Vani |

grandfather-yours |

he-say |

he_SUBJ-rise |

|

ku-yì |

kái |

ŋwî |

ku-dòg |

zə̀g |

mə̀ŋ |

bá |

dámá |

|

he-say |

you |

saying |

he-rise |

take |

NEG |

NEG |

possibility |

|

kú-dòg |

á-dòg |

àré |

ŋwà |

ku-yì |

ku-dòg |

zə̀g |

mə̀ŋ |

|

he_SUBJ-rise |

you_SUBJ-rise |

here |

must |

he-say |

he-rise |

take |

NEG |

|

vánì |

ye |

dù-kù |

vo |

à |

ke |

tahwàr |

ǹ-dàd |

zə̀g |

sàk |

áhwàì |

|

Vani |

go |

lift-him |

hand |

PREP |

here |

armpit |

CONS-take |

take |

hang |

neck |

|

m̀pə̀ŋə̀ |

bìy |

naì |

m̀pə̀ŋə̀ |

bìy |

ánə́rì |

há̰ |

hwáì |

àhá |

|

youth |

come |

laying |

youth |

come |

ancient |

as |

big |

that |

|

ku-dàd |

zə̀g-wà |

sàk |

rə̀ |

áhwàì |

ku-dàd |

zə̀g |

zuì |

só |

nə́m |

|

he-take |

take-him |

hang |

PERFVE |

neck |

he-take |

take |

passing |

there |

like_that |

|

bâ |

bìy |

ǹ-bìy |

kàd |

à |

káy |

há̰ |

ǹ-zə̀g |

sh1i |

|

Ba |

come |

CONS-come |

enter |

PREP |

home |

as |

CONS-take |

beer |

|

jánu |

wù |

rí |

yéy |

sh1i |

|

ancestor_mask |

cook |

FOC |

there |

beer |

|

bərí-kùrù |

wù |

rí |

yéy |

bá-jâw |

vánì |

rí |

wéy |

|

COLL-king |

cook |

FOC |

there |

people-friend |

Vani |

FOC |

see |

|

jánu |

à |

ke |

à |

káy |

ku-yì |

ŋwù |

ŋwà-zə̀m |

|

ancestor_mask |

PREP |

here |

PREP |

home |

he-say |

son |

he_REF-answer |

|

ŋwà-mə́n |

nə́m |

wéy |

jánu |

mə̀ŋ |

ŋwà-yì |

ḿ |

|

he_REF-touch |

like_that |

see |

ancestor_mask |

NEG |

he_REF-say |

yes |

|

bə-yì |

márì |

m̀pə̀r |

ye |

yag |

pàr |

rə̀k |

|

they-say |

blessing |

person |

go |

go |

masses |

PERFVE |

|

ku-dàd |

zə̀g-wà |

ye |

yag |

rí |

ku-yì-yag |

wúd |

sh1i |

jánu |

|

he-take |

take-him |

go |

go |

FOC |

he-CONT-go |

cook |

beer |

ancestor_mask |

|

à |

bo |

kə̀m |

|

PREP |

place_to |

different |

|

ku-sə́g |

à |

bo |

bìy |

bə́ |

bá-jâw-wà |

wéy |

|

he-stay |

PREP |

place_to |

come |

with |

people-friend-his |

see |

|

jánu |

rə̀g |

ku-yì-wéy |

jánu |

rí |

à |

|

ancestor_mask |

PERFVE |

he-CONT-see |

ancestor_mask |

FOC |

PREP |

|

bo |

be-wà |

rí |

ǹ-bìy |

ré |

|

place_to |

place-his |

FOC |

CONT-come |

IMPVE |

|

vánì |

kùkú-nə̀ŋ |

àré |

bâ |

gbán |

lòw-yì |

|

Vani |

grandfather-your |

there |

thing_that |

kill |

house-our |

|

na-wà |

ke |

gbán |

néy |

àhá |

néy |

jírí |

kùrù |

bâ |

ke |

|

lie-it |

here |

destroy |

that |

yes |

that |

issue |

king |

thing_that |

here |

|

jáná |

kùrù |

ná |

má-na-nə́ŋ |

mə̀ŋ |

bú-zṵ̀ŋ |

à-jì |

ye |

jì |

bámə̀ŋ |

|

children |

king |

lie |

COND-lie-resemble |

NEG |

thing-one |

eating |

go |

eat |

not_there |

|

nə́ŋ-wéy |

áyi-sə́d |

hámá |

bú |

jì |

nə́m |

yámà |

mə̀ŋ |

há̰ |

kànì |

ho |

də̀rì-yì |

|

you-see |

that_we-stay |

how |

thing |

eat |

like_that |

anyhow |

NEG |

as |

war |

collect |

body-our |

|

bo |

à |

bo |

kú-rò |

hár |

sə́d |

sə́d |

sə́d |

sə́d |

sə́d |

|

place_to |

PREP |

place_to |

priest-LOC |

from |

stay |

stay |

stay |

stay |

stay |

|

yì-bìy |

rí |

fád |

ré |

há̰ |

àmá |

ǹ-zə̀n |

kànì |

bámə̀ŋ |

àsírí-yì |

|

CONT-come |

FOC |

reach |

IMPFVE |

as |

but |

CONS-fear |

war |

not_there |

secret-our |

|

àré |

bâ |

àsa |

kànì |

gbán-yì |

kànì |

ke |

bâ |

àbìy |

gbán-yì |

hàná |

|

that |

thing_that |

doing |

war |

destroy-us |

war |

here |

thing_that |

coming |

destroy-us |

like_this |

|

i-fyág |

ho-bà |

ke |

há̰ |

tə̀rí |

nə́m |

pyénà |

rí |

ke |

|

we-find |

collect-them |

here |

as |

be_present |

like_that |

two |

FOC |

here |

|

wùrù-rò |

bá-wùrù-rò |

fyág |

àré |

i-fyág |

ho |

tə̀rí |

má-rí-hàmá |

|

Wuru-LOC |

people-Wuru-LOC |

find |

there |

we-find |

collect |

be_present |

COND-IMPFVE-now |

|

nə́ŋ-má-yì |

ǹ-ye |

ǹ-zə̀g |

bìy |

mèy |

ye |

ǹ-zə̀g |

bìy |

|

you-COND-say |

CONS-go |

CONS-take |

come |

leave |

go |

CONS-take |

come |

|

áku-bìy |

wéy |

ái |

na |

nə́m |

kó |

àhá |

bú |

àbìy |

gbán |

də̀rì-yì |

gàrù |

|

that_she-come |

see |

just |

lie |

like_that |

or |

this |

thing |

coming |

destroy |

body-our |

wall |

|

n-yag |

fád |

rí |

bo |

be |

wùrù |

rí |

bə́ |

də̀rì-mì |

rí |

|

I-go |

reach |

FOC |

place_to |

place |

Wuru |

FOC |

with |

body-my |

FOC |

|

ŋwù |

kə́ngbá |

dàbàŋ |

àsaì |

fyág |

rə̀ |

zṵ̀ŋ |

də̀rì-mì |

n-fyág |

rə̀ |

zṵ̀ŋ |

|

child |

Bachama |

Dabaŋ |

maker |

find |

PERFVE |

one |

body-my |

I-find |

PERFVE |

one |

|

i-fyág-à |

zo |

kùrù |

shúmen |

rí |

|

we-find-it |

time |

king |

Shumen |

FOC |

|

kùrù |

dà̰w |

bìy |

há̰ |

ŋwî |

áku-wéy |

bə-dàd |

zə̀g |

rí |

yí-kù |

|

king |

Dãw |

come |

as |

saying |

that_he-see |

they-take |

take |

FOC |

give-him |

|

zṵ̀ŋ |

sə́d |

bo |

be-à |

rí |

zṵ̀ŋ |

kà̰ŋ |

rí |

sə́d |

ke |

yì-rò |

|

one |

stay |

place_to |

place-his |

FOC |

one |

reverse |

FOC |

stay |

here |

our-LOC |

|

bú |

àgbán |

gàrù |

n-ye |

zə̀g |

bìy |

áku-bìy |

wéy |

də̀rì-bə̀ |

|

thing |

destroying |

wall |

I-go |

take |

come |

that_she-come |

see |

body_their |

|

bàturè |

sə́d |

a-yì |

nə́m |

bə-wéy |

nə́m |

àhá̰ |

n-yag |

rə́ |

réwà |

|

European |

stay |

you-know |

like_that |

they-see |

like_that |

as |

I-go |

IMPFVE |

soon |

Zorei Nunoye’s account of Kona’s oral history is structured as follows: [10]

-

Early migration

-

War and jihad; founding of Kona

-

Fortification of Kona

-

Competition for chieftaincy; Ba’s betrayal

-

Ba performs magic and destroys Kona's spiritual protection

-

Description of the fight; a swallow as a magic defence

-

Heroic fight of the guard Numtayi

-

The Bachama flee

-

Vani carries King Inu out of the burning town

-

Ba initiates Vani

-

Lament and praise for the Jibe warriors

-

Where the mortars are today

<36>

The first part of text (1) deals with the migration from Kuro to an open space where baobab trees were growing. This migration was probably encouraged by disputes over chieftaincy or similar important titles. Apart from this, ethnohistory of Kona emphasizes that an important sculpture and a magic golden stone – parts of a major shrine of the Jibe – fell into the River Benue at Kuro, so that migration could not continue until the objects were retrieved. After a terrible drought they were recovered and have been kept ever since in the community’s major shrines.

<37>

In the second paragraph (2) we are told that somebody – a Fulçe man called Buba – came to the Jibe in order to advise them to move to a safer, better-protected area. Informants like this person were common on both sides – Jibe and Fulçe – and crossed the borders between enemies in order to betray their own people and to get a reward for their information. Most likely the Jibe had stayed in an open area because they did not know how to cross the mountains; after having been shown a secret passage through the wilderness they settled at the present site of Kona under their chief Agauwa. As aggression always came from the North and the passage to the South through the mountains was secret (while the southern side was safe) the site of Kona was wisely chosen.

<38>

The text continues with a description of the fortification of the newly established town. (3) There were normally two options for safety: weapons (bow and arrow, spears) or a fortification wall. Under the legendary chief Agauwa, who must have known similar structures from northern towns, a wall was built and Kona became known as gàrù, after the Hausa word for ‘wall’. Building took about three years, as the fortification was often restructured because many migrants were still moving to Kona. The wall had two major gates which were always protected. Every clan was responsible for the maintenance of a certain part of the wall.

<39>

After establishing the town, building the fortification wall and restructuring the society in a way that clans would share and divide work and responsibilities, Kona was well-protected against local enemies and the Fulɓe Jihadists. Now (4) a person called Ba of the clan Banojiri, who belonged to the group of the noblemen or kingmakers, wanted to become chief, and in order to betray the current leader he gave some secret information to the enemy. After this information had been passed to the Fulɓe they came armed with guns and attacked Kona. But every time they tried to shoot, something happened to their weapons. So the Fulɓe became convinced that the inhabitants of Kona were in possession of some powerful magic or secret. Eventually, the Fulçe would rather ask persons from neighbouring ethnic groups such as the Bachama or even Europeans to fight against such dangerous enemies instead of wasting their own people. The Bachama apparently fought against Kona before, but out of fear of magic, they rather established a joking relationship with the Jibe. Since this time, an old Jibe woman is regularly sent to care for a shrine in a Bachama commmunity, a rare example of a Jibe who holds a female title.

<40>

Meanwhile, Ba, whose betrayal had not yet led to any result, performed magic rites in order to destroy the town’s secret and its spiritual protection. (5) Kona thus was conquered by the Fulçe, whose warriors were led by Ba. That Europeans aided the Emir in conquering Kona by bombarding the fortification wall is only of marginal interest here: had Ba not destroyed the town's spiritual powers before (which he as an initiated Jibe could do), the bombardment would not have harmed Kona. The focus of the description of the fight and destruction lies on how a last magical protection of the town, a swallow, almost defeated the attacking warriors (6), when Ba finally succeeded. Before Kona is lost and destroyed, a prototype of a brave Jibe warrior is depicted: (7) Numtayi, who guards the town’s gate, is already severely wounded and almost buried by the ruins of the wall, when he throws his two remaining spears (Jibe warriors usually used three different types of spears) at a European soldier, whom he kills. Then he is overwhelmed by the other soldiers and decapitated.

<41>

As Kona is burning, the Bachama, who settle nearby, already let their women flee to the mountains. (8) In Kona, Numtayi’s enormous strength and power is not exceptional, as Vani, a boy who is not yet initiated, appears on the scene. (9) King Inu, desperate, sits on a stone in front of his palace and sees how his town burns down to the ground. Unable to move, he waits for death. In Jibe society, suicide is regarded as a noble action when a situation has become hopeless and one's dignity has been lost. As such, suicide would be an acceptable way for Inu to end the dramatic competition with Ba, but Vani carries the chief in his arms out of the burning town and saves him. Impressed by such loyalty and integrity, Ba, who is just performing rites for the spirits, decides to initiate Vani, who has not yet reached the age to take part in the men’s secret activities. (10) Vani is thus taken to a secret place, where the other boys are already in contact with the spirits. Vani sees the spirits and is initiated into his clan’s shrine and later becomes one of the community’s outstanding heroes.

<42>

The emphasis Zorei Nunoye lays on the physical and spiritual strength of the male Jibe has a historical background which dates back to the founding of Kona: King Agauwa, who had the wall built, restructured his people as a society of warriors, who were organized within the secret societies of their clans’ shrines. The men's social activities consisted mainly in the secret religious rites they performed at the shrines and in competitions in fighting and shooting with bow and arrow. The self-estimation of Jibe men as mighty and powerful warriors persists, even though fighting has ceased in the 1930s. Women, on the other hand, are carefully kept away from the men’s secret places and activities, and it is characteristic of their exclusion from religious activities that there were hardly any women in the audience listening to Zorei Nunoye’s account of Kona's history.

<43>

The text ends with a lament on those conflicts which always weakened the society and with praise for the strong men of Kona, who always reunite in times of war. (11) At the end, we are told how the mortars were found and where they are today. (12) Zorei Nunoye offered to bring one of them, which was kept in the house of the Wuru, an important traditional titleholder. He left his clan’s gathering place and later came back with a rusty piece of iron, which once destroyed his town, but not his people’s magical powers.

Adelberger, Jörg 2000

'Eduard Vogel and Eduard Robert Flegel: Experiences of two 19th century German explorers in Africa.' In: History in Africa 27:1-29.

Adeleye, R.A. 1971

Power and Diplomacy in Northern Nigeria 1804–1906. New York: Humanities Press.

Alis, Harry 1894

Nos Africains. Paris: Hachette

Baker, Geoffrey L. 1996

Trade Winds on the Niger. The Saga of the Royal Niger Company 1830–1971. London, New York: Radcliffe

Chabredier, (Adjudant) 1894

'La seconde mission du lieutenant Mizon.' Journal des Voyages et des Aventures de Terre et de Mer 876:178–179, 198–199, 212–214, 227–228, 242–243, 258–259, 275–276, 294–295

Crowder, Michael 1962

The Story of Nigeria. London, Boston: Faber & Faber

Dinslage, Sabine and Anne Storch 2000a

'Gender and Magic in Jukun Folktales.’ Estudos de Literatura Oral 5:151-160

Dinslage, Sabine and Anne Storch 2000b

Magic and Gender . Cologne: Köppe

Dusgate, Richard H. 1985

The Conquest of Northern Nigeria. London: Frank Cass

Fabian, Johannes 2002

'Virtual Archives and Ethnographic Writing: Commentary as a New Genre?' Current Anthropology 43:775-86

Fabian, Johannes 2008

Ethnography as Commentary. Writing from the Virtual Archive. Durham, NC: Duke University Press

Flint, John E. 1960

Sir George Goldie and the Making of Nigeria. London, Ibadan, Accra: Oxford University Press

Hogben, Sidney John and Anthony H.M. Kirk-Greene 1966

The Emirates of Northern Nigeria. London: Oxford University Press

Le monde illustré 1893

No. 1912, Paris

Mason, M. G. 1968

'An Annotated Bibliography of Eduard Flegel’s Expeditions in the Niger-Benue Region 1879-86.' In: Kano Studies 1,4:97-112

Meek, C. K. 1931

A Sudanese Kingdom. London.

Meek, C. K. n.d.

“The Kona” in SNP 17 - K 3187 “Kona Tribe, Adamawa Province - Anthropological Notes on by Mr. G. W. Webster 1912 and Mr. Meek 1928”. National Archives, Kaduna.

Mizon, L. 1892

'En plein Soudan.' Journal des Voyages et des Aventures de Terre et de Mer 31:132–132, 150–151, 162–163, 186–188, 202–203

Pakenham, T. 1992

The scramble for Africa , 1876–1912. London: Abacus

Stevens, P. 1975

'The Kisra legend and the distortion of historical tradition.' Journal of African History,16,2:185-200

Storch, Anne 1999

Das Hone und seine Stellung im Zentral-Jukunoid. Cologne: Köppe

Storch, Anne 2005

'Traces of a secret language – Circumfixes in Hone (Jukun) plurals.' In: A. Akinlabi (ed.) Proceedings of the 4th World Conference of African Languages , Cologne: Köppe

Storch, Anne in print

'Cultured Contact: Ritualisation and Semantics in Jukun.' In: W.J.G. Möhlig et al. (eds.) Contact Scenarios and Language Change in Africa. SUGIA. Cologne: Köppe

Surun, Isabelle 2007

'Les figures de l’explorateur dans la presse du XIXe siècle.' Le Temps des Médias 8:57-74

Vansina, J.1985

Oral Tradition as History. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press

Webster, J.B. 1994

Kwararafa: the traditional face of the coin. Boston: ms.

[1] This contribution is based on data that was collected during fieldwork on Kona, Nigeria, in 1996, which was generously funded by the German Research Society. The authors are grateful to John Shumen, Barnabas Vakkai and Edward Shaukei who shared their knowledge on nám Jibe with us, and to Most Rev. Dr. Ignatius Kaigama for his many insightful comments. We are deeply indebted to Zorey Nunoye for his patience and his readiness to tell us stories during daytime and at odd seasons. We thank Monika Feinen for drawing the map and two anonymous peer reviewers for their helpful comments.

[2] Our colleague Sabine Dinslage was also a member of the team.

[3] Jibə is a Northern Jukunoid (or Central Jukunoid) language of the Central Nigerian branch of Benue-Congo (Storch 1999).

[4] See Fabian (2002 & in print) for a critical account on ethnographic sources as commentaries.

[5] The following description of the principal course of events is based on Alis 1894:472-485, especially 480-485 (Harry Alis was the pseudonym of the journalist Hippolyte Percher) and Chabredier 1894, with useful additions from later studies:Adeleye 1971:146–159, Baker 1996:136–144, Dusgate 1985:41-45, Flint 1960:167-179, especially 175-176, Pakenham 1992:361–362, 452–456.

[6] Eduard Robert Flegel was a German explorer who travelled extensively in the various regions of the Sokoto caliphate, and especially in Adamawa, from 1879 to 1886, when he died of illness in Brass in the Niger delta. He tried to expand German colonial activities and trade in these areas, but his efforts were eventually frustrated by the agreements found during the ‘Berlin conference’. For a bibliography of his writings see Mason 1968; see also Adelberger 2000.

[7] See Surun (2007) for a recent study of the iconography of explorers in illustrated French journals of the 19th century.

[8] mam ‘create; creation’ is one important aspect of the religion of Kororofa; cf. Meek 1931, Storch 2005 & in print.

[9] Remarks

Jibə has three tones: low [à], mid [a] and high [á]. The following abbreviations have been used in the glossing of the text:

|

COND |

conditional |

|

CONS |

consecutive |

|

CONT |

continuative |

|

FOC |

focus |

|

FUT |

future |

|

IMPFVE |

imperfective |

|

INTERR |

interrogative |

|

LOC |

locative |

|

NEG |

negation |

|

PERFVE |

perfective |

|

PREP |

preposition |