A synchronic and diachronic examination of the ex-situ term focus construction in Fulfulde of Fuuta Jaloo (Guinea)

urn:nbn:de:0009-10-41558

Zusammenfassung

Der vorliegende Artikel beschreibt die am häufigsten genutzte Termfokuskonstruktion im Fulfulde-Dialekt des Fuuta Jaloo (Guinea) und stellt Hypothesen zur synchronen Analyse sowie zu ihrer Entstehung vor. Obwohl dieser Dialekt von ca. 3 Millionen Muttersprachlern gesprochen wird, wurde er trotz der signifikanten Unterschiede zu seinen Nachbardialekten in der linguistischen Forschung bisher nur marginal berücksichtigt. Zunächst beschreibe ich die entsprechende Konstruktion ausführlich und erkläre im Anschluss daran, warum ich diese nicht als Spaltsatz analysiere, auch wenn das für die senegalesische Fulfulde-Varietät angenommen wird. Die vorliegende ex-situ-Konstruktion hat vielmehr eine spaltsatz-ähnliche Struktur. Abschließend diskutiere ich zwei Hypothesen: 1) die Grammatikalisierung eines ehemaligen Spaltsatzes hin zur heutigen Termfokuskonstruktion, und 2) die Idee, dass vielmehr die identifizierende Funktion des Fokussatzes und die zugleich hintergrund-markierende Funktion des subordinierten Satzes die Entstehung der Fokuskonstruktion bedingt haben. Die Argumente für beide Hypothesen sind gleichermaßen überzeugend, sodass keine der anderen vorgezogen werden kann.

Abstract

The present paper describes the most frequent construction type for term focus in Fulfulde of Fuuta Jaloo (Guinea) and discusses hypotheses for its synchronic analysis and its diachronic development. Although this dialect has around 3 million speakers, little attention was paid to it in linguistic research in spite of the significant differences it shows to its neighboring dialects. After describing the ex-situ term focus construction in detail, I will argue that we are not dealing with a cleft sentence as it is assumed in the Senegalese variety, but rather with a cleft-like structure. Subsequently I will discuss two hypotheses: 1) a grammaticalization of a former cleft towards its present-day focus construction, and 2) the identificational function of the focus clause and the backgrounding function of the out-of-focus clause as a driving force for the development of the construction. The arguments for both scenarios being convincing, no hypothesis can be clearly preferred over the other one.

<1>

Fulfulde is a West Atlantic language of the Niger-Congo family spoken in 18 countries from Western to Central Africa with around 22 million speakers (Gajdos 2004). Due to this vast geographic expansion, dialects differ significantly from each other in their morphology, lexicon and syntax. While some of the ten major varieties such as Pulaar (Senegal), Maasina (Mali) or Adamawa (Cameroon, Nigeria) have received a lot of attention in linguistic research in the past, investigation on the dialect of Fuuta Jaloo, especially regarding information structural aspects, is still scarce.

<2>

The present paper will discuss the most frequent construction type for the expression of term focus, which is characterized by five features:

-

syntactic marking by a bi-clausal structure

-

syntactic marking exploiting the sentence-initial position

-

morphological marking of the focused element using a special term focus marker

-

morphological marking of the background clause using special verb forms which merge information on tense/aspect/mood as well as on voice and focus, comparable to other Atlantic languages (Robert 2010)

-

prosodic marking

The relation between the term focus marker, the copula and the identificational marker – all being homophones – on the one hand, and the relation between the usage of the same verb forms in term focus constructions and other background clauses on the other hand, seem to point to the origin of these constructions. Basing their analysis mainly on the verb forms, some authors arrive at the conclusion that the ex-situ term focus construction must be analyzed as a cleft in the Senegalese variety (see Fagerberg 1983, Sylla 1993). While this construction type is well described in the literature (e.g. Diallo & Ermisch forth.), no previous hypothesis on its origin or mention of its relation to other subordinate constructions have been made so far. Thus, the present paper tries to shed light on this question.

<3>

The paper is structured as follows: in section 2, I will set up briefly the theoretical framework for my definition and analysis of focus and its categories. Section 3 will then present the syntactic and morphological features of the ex-situ term focus construction of Fulfulde of Fuuta Jaloo, paying special attention on the verb forms and on the nature of terms which can be focalized ex-situ. In section 4, I will discuss the possibility of analyzing this construction as a cleft and provide arguments against this analysis. Section 5 will then present and discuss two hypotheses on the diachronic development of the ex-situ term focus construction. The final section 6 will summarize the presented hypotheses and give an outlook for further research.

<4>

Human communication serves to exchange information between individuals, which makes it necessary to structure this information in the communicative setting. I follow the Collaborative Research Center 632 in defining information structure (IS) as

"the structuring of linguistic information, typically in order to optimize information transfer within discourse. The underlying idea is that the same information needs to be prepared or ‘packaged’ in different ways depending on the background and the goal of the discourse". (CRC 632)

In this respect, research on information-structural aspects takes into account the relevant formal levels phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax and semantics.

<5>

One of the basic notions of IS is the term focus which is defined differently in the literature. In the present paper, I adopt Dik’s (1997) definition of focus within the functional framework. A focal information on the sentence level is thus understood as “that information which is relatively the most important or salient information in the given communicative setting, and considered by S [the speaker] to be most essential for A [the addressee] to integrate into his pragmatic information” (Dik 1997:326).

<6>

Apart from defining four different focalizing devices (prosodic prominence, special constituent order, special focus markers and special focus constructions), Dik (1997) determines two main parameters for the subcategorization of focus:

-

the scope of focus,

-

differences in communicative point.

The first parameter indicates whether the scope is over a term (e.g. the subject, object, etc.), over a predicate (verb lexeme) or over a predicate operator (tense, aspect, mood, polarity operators) (ibid.:330f.). The second parameter is used to distinguish two different focus strategies: completive focus (which is called “assertive focus” in the remainder of this paper, following Hyman & Watters 1984), which closes an information gap (e.g. by asking a wh-question, example 1), and contrastive focus, which can be subclassified into rejecting, replacing, expanding, restricting or selecting a piece of information (example 2):

|

(1) |

Assertive focus on the object |

|

Q: What do you like to eat today? |

|

|

A: I would love to eat PIZZA today. |

|

(2) |

Contrastive (selective) focus on the object |

|

Q: Do you want tea or coffee? |

|

|

A: I want TEA, please. |

Both parameters are not independent but interact with each other and may have influence on the realization of focus.

<7>

A general, cross-linguistic observation is that contrastive focus tends to involve a special grammatical marking (e.g. intonation contour, syntactic movement, clefts or morphological markers) in comparison to non-contrastive focus (Zimmermann 2007). The next section will show whether this observation holds also true for the Fulfulde data.

<8>

The most frequent strategy for focalizing a term (subject/object NP (or parts of it) or adverbial) in Fulfulde involves a bi-clausal structure being its first feature:

-

Syntactic marking: the ex-situ term focus construction possesses a bi-clausal structure.

The first part contains the focalized element and will therefore be called in the following “focus clause”, the second one provides as “out-of-focus clause” the background information. Two aspects define the focus clause:

-

Syntactic marking: the focalized term stands in the sentence-initial position.

-

Morphological marking: the term focus marker ko precedes the focalized term forming with it the focus clause.

The fourth characteristic of the term focus construction is located in the out-of-focus clause:

-

Morphological marking: only one specific verb form for each perfective and imperfective is allowed, namely the perfective 2 and the imperfective 4.

<9>

The two verb forms are identical to those used for relative and other background clauses and will be discussed in detail below. The word order in the out-of-focus clause stays canonical: being an SVO language, prepositional phrases and manner adverbs are preferred sentence-finally, whereas time adverbs may be also placed sentence-initially (Diallo 2000). It is important to point out that the element which is focalized is not repeated in the out-of-focus clause.

On the suprasegmental level, there is a change of what Diallo & Ermisch (forth.) call the sentence melody (see also Anyanwu & Diallo 2005), being the fifth feature:

-

Prosodic marking: primary stress is placed on the initial syllable of the focused element.

<10>

The prosody of focus constructions is thus different from neutral affirmative sentences where stress is placed on the verb root. In the following, I will discuss the morphosyntactic marking in more detail; hence no attention will be paid on the prosodic marking (see e.g. Anyanwu & Diallo 2005 or Bao 2012, the latter working on subject focus in the Senegalese variety).

The characteristics of the ex-situ term focus construction can be schematized as follows:

|

Figure 1: Scheme of the bi-clausal structure |

||

|

Ko X |

(S) V (O) (Z) |

|

|

focus |

out-of-focus |

|

|

clause |

clause |

|

<11>

In the focus clause, we have the term focus marker ko and the focalized term X. Note that focalized pronouns will stand in their emphatic form. This first part of the bipartite structure is followed by the out-of-focus clause consisting of the subject S, the verb V, the object O and other elements Z (adverbs, prepositional phrases, etc.); the brackets indicate that once the subject, object or adverbial is focalized, it leaves no morphological trace in the out-of-focus clause.

<12>

Before going into detail regarding the verb form and the elements which can occur in the focus clause preceded by the term focus marker, I want to exemplify the described observations so far. Example (3) illustrates a neutral declarative sentence:

|

(3) |

Neutral declarative sentence |

||

|

Maria |

sood-ay |

welo. |

|

|

pn |

buy-a.ipfv3 |

bicycle.1 |

|

|

ʻMaria will buy a bicycle.ʼ |

|||

The sentence displays the canonical word order SVO, the active verb is conjugated in the imperfective 3 (the numbering will be explained shortly).

If the object is now in focus, e.g. after the question “What will Maria buy?”, the ex-situ structure will be:

|

(4) |

Assertive focus on the object |

|||

|

Ko |

welo |

Maria |

sood-ata. |

|

|

t.foc |

bicycle.1 |

pn |

buy-a.ipfv4 |

|

|

ʻ[What will Maria buy?] Maria will buy a BICYCLE.ʼ |

||||

The object occurs now in sentence-initial position preceded by the term focus marker, the second part of the clause maintains the canonical word order leaving a gap in the canonical object position. The verb is still conjugated in active voice, but now in the verb form imperfective 4.

<13>

As the further analysis of the construction will be partly based on the verb forms, it is necessary to look at them more closely. The verb system of Fulfulde is rather based on aspect than on tense; therefore in the literature three perfective verb forms are opposed to four imperfective verb forms. This asymmetry is due to the fact that in the traditional Fulfulde literature moods such as imperative and subjunctive are counted among the imperfective paradigm. In order to distinguish the verb forms within the perfective or imperfective, they are often simply numbered, although the number does not imply a specific meaning. Besides the division between perfective and imperfective, verbs may be conjugated in three different voices: active (a), middle (midd) and passive (pass).

The only verb forms permitted in the ex-situ construction are the forms perfective 2 and imperfective 4, having the following morphological shape in active, middle and passive voice:

|

Table 1: The verb suffixes in ex-situ term focus constructions |

|||

|

Voice |

Perfective 2 |

Imperfective 4 |

|

|

active |

-i |

-ata |

|

|

middle |

-ii |

-otoo |

|

|

passive |

-aa |

-etee |

|

<14>

In contrast to all other verb forms, the short subject pronouns of the 1st person singular (only in a few regions of the Fuuta Jaloo accepted), 2nd person singular, 1st person plural inclusive and 2nd person plural obligatorily follow the verb complex (i.e. verb root+TAM-suffix) in the perfective 2 and imperfective 4 modifying phonologically the verb forms above:

|

Table 2: The verb suffixes in ex-situ term focus constructions with encliticized subject pronouns |

|||||

|

voice |

Perfective 2 |

imperfective 4 |

|||

|

active |

-u- |

-ay-/-at-/-et-/-ot- |

|||

|

middle |

-i- |

-oto(o)- |

|||

|

passive |

-a- |

-ete(e)- |

|||

The encliticized pronouns induce a vowel change in the active forms (in the imperfective every enclitic pronoun triggers an own form, for details see Diallo 2000:171), in the middle and passive voice they lead to a vowel shortening (only the 1st person singular enclitic does not evoke this phonological process in the imperfective). Note that the same changes happen when the preterite marker -no(o) is suffixed to the verb.

<15>

Example (5) illustrates this process for the short subject pronoun of the 3rd person singular which never cliticizes and the subject pronoun of the 2nd person singular which is obligatorily cliticized inducing the vowel change of the TAM-suffix:

|

(5) |

Preverbal short subject pronoun |

|||||

|

a. |

Ko |

hanki |

o |

wind-i. |

||

|

t.foc |

yesterday |

3s |

write-a.pfv2 |

|||

|

ʻS/he wrote YESTERDAY.ʼ |

||||||

|

b. |

Enclitic subject pronoun |

|||||

|

Ko |

hanki |

wind-u-ɗaa. |

||||

|

t.foc |

yesterday |

write-a.pfv2-2s |

||||

|

ʻYou wrote YESTERDAY.ʼ |

(adapted from Diallo 2000:119) |

|||||

The two verb forms perfective 2 and imperfective 4 are not only restricted to the usage in term focus constructions, but they occur also in narration, with stative verbs, in relative clauses, pseudo-clefts, temporal clauses and interrogatives.

<16>

Interrogatives are a good starting point to examine what kind of terms can be focalized in the focus clause as wh-questions in Fulfulde make use of the same ex-situ construction. The question word which is inherently in focus stands sentence-initial and is preceded by the term focus marker ko, the verb forms in the out-of-focus clause are restricted to the perfective 2 and imperfective 4 as described above. Hence, wh-questions can be schematized as in Figure 2:

|

Figure 2: Wh-questions in Fula of Fuuta Jaloo |

||||

|

hombo |

‘who’ |

|||

|

honɗun |

‘what’ |

|||

|

Ko |

honto |

‘where’ |

(S) V (O) (A) |

|

|

fii honɗun |

‘why’, lit. ‘for what’ |

|||

|

honno |

‘how’ |

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

[focus clause] |

[out-of-focus clause] |

|||

Apart from wh-questions, objects and adverbials, the ex-situ construction is used for focus on the nominal and pronominal subject, illustrated in example (6):

|

(6) |

Assertive focus on the subject |

|||||

|

Q: |

Ko |

hombo |

faal-aa |

ɲaam-ugol |

pute? |

|

|

t.foc |

who |

want-pass.pfv2 |

eat-a.inf |

sweet.potato.1 |

||

|

ʻWHO wants to eat sweet potato?ʼ |

||||||

|

A1: |

Ko |

Maria |

faal-aa |

ɲaam-ugol |

pute. |

|

|

t.foc |

pn |

want-pass.pfv2 |

eat-a.inf |

sweet.potato.1 |

||

|

ʻMARIA wants to eat sweet potato.ʼ |

||||||

|

A2: |

Ko |

kanko |

faal-aa |

ɲaam-ugol |

pute. |

|

|

t.foc |

3s.emph |

want-pass.pfv2 |

eat-a.inf |

sweet.potato.1 |

||

|

ʻS/HE wants to eat sweet potato.ʼ |

||||||

<17>

In example (6A1), the subject is a proper name, but can be replaced by any NP. The length of this NP is not restricted: The focalized subject NP may be indefinite or definite, a proper name, a pronoun or may be enlarged by a quantifier, qualifier or a (pro-)nominal possessor. When more than one word is contained in the NP, e.g. a noun and a quantifier, the whole NP or only part of it is in the scope of the term focus marker. This means that ex-situ focus constructions with larger NPs in the focus clause are potentially ambiguous, because only a part of the NP is semantically in focus while the whole NP is marked. Examples (7) and (8) illustrate this ambiguity for subject and object focus:

|

(7) |

Assertive focus on the subject as a whole or its quantifier |

|||||

|

Ko |

wor-ɓe |

ɗiɗo |

won-i |

naɓ-ude |

legg-al |

|

|

t.foc |

man-2 |

two |

exist-a.pfv2 |

bring-a.prog |

tree-11 |

|

|

ʻ[WHO is carrying a log?] TWO MEN are carrying a log.ʼ |

||||||

|

ʻ[HOW MANY men are carrying a log?] TWO men are carrying a log.ʼ |

||||||

|

(8) |

Contrastive (selective) focus on the object as a whole or its qualifier |

|||||

|

Ko |

coonc-i |

danee-ji |

ɗin |

mi |

faal-aa. |

|

|

t.foc |

cloth-4 |

white-4 |

def.4 |

1s |

want-pass.pfv2 |

|

|

ʻ[Do you want the WHITE´CLOTHES or the BLACK SHOES?] I want the WHITE´clothes.ʼ |

||||||

|

ʻ[Do you want the white or the black clothes?] I want the WHITE clothes.ʼ |

||||||

The ex-situ construction is also used for focalizing adverbial phrases:

|

(9) |

Contrastive (selective) focus on the manner adverb |

|||

|

Ko |

heɲa |

o |

ɲaam-ir-i. |

|

|

t.foc |

quickly |

3s |

eat-instr-a.pfv2 |

|

|

ʻ[HOW did the woman eat? QUICKLY or SLOWLY?] She ate QUICKLY.ʼ |

||||

|

(10) |

Assertive focus on the time adverb |

||||

|

Ko |

hanki |

o |

sakkit-ii |

ɲaam-ugol. |

|

|

t.foc |

yesterday |

3s |

be.last-midd.pfv2 |

eat-a.inf |

|

|

ʻ[WHEN did the woman eat the last time?] She ate the last time YESTERDAY.ʼ |

|||||

<18>

To finish this overview of elements that can be focalized ex-situ, I want to give two last examples: Comparable to the examples (7) and (8) above, longer terms as prepositional phrases (example 11) and adverbial clauses (example 12) can be focalized ex-situ. Therefore, the whole phrase or clause is in sentence-initial position preceded by ko:

|

(11) |

Contrastive (selective) focus on the prepositional phrase |

|||||

|

Ko |

ka |

laaw-ol |

o |

ɲaam-ata |

jango. |

|

|

t.foc |

prep |

road-14 |

3s |

eat-a.ipfv4 |

tomorrow |

|

|

ʻ[WHERE will the woman eat tomorrow? At home or on the road?] She will eat tomorrow ON THE ROAD.ʼ |

||||||

|

(12) |

Assertive focus on the adverbial clause |

||||||||

|

Ko |

fii |

hari |

himo |

weel-aa |

o |

ɲaam-i |

ɲeɓɓ-e |

ɗen. |

|

|

t.foc |

for |

pst |

3s |

be.hungry-pass.pfv2 |

3s |

eat-a.pfv2 |

bean-3 |

def.3 |

|

|

ʻ[WHY did the woman eat the beans?] She ate the beans BECAUSE SHE WAS HUNGRY.ʼ |

|||||||||

<19>

The data shown so far represent always sentences with one focalized term. But how are sentences with two semantic foci structured? The question/answer-pair in example (13) illustrates such a semantic multiple focus:

|

(13) |

Assertive multiple focus |

||||

|

Q: |

Ko |

hombo |

waɗ-i |

honɗun? |

|

|

t.foc |

who |

make-a.pfv2 |

what |

||

|

ʻWho did what?ʼ |

|||||

|

A: |

Ko |

Mari |

piy-i |

Mouctar. |

|

|

t.foc |

pn |

beat-a.pfv2 |

pn |

||

|

ʻMary hit Mouctar.ʼ |

|||||

<20>

Although semantically there are two foci – one on the subject and one on the VP – only the term can be marked syntactically and morphologically. Field work data reveals that if one of these foci is on the subject, this one will be chosen for the sentence-initial position preserving the canonical word order, as in example (13). This observation can be explained by the fact that an unmarked subject is usually interpreted as the sentence topic, while an unmarked object is more likely interpreted as focal information. Hence, when the subject is not topical but focal, this needs to be marked additionally (see Fiedler et al. 2010).

We can now summarize the observations made on the ex-situ term focus construction in this section:

-

syntactic marking by its bi-clausal structure;

-

syntactic marking by the sentence-initial position;

-

morphological marking by the term focus marker ko which precedes the focalized term;

-

morphological marking by the restriction on the verb forms perfective 2 and imperfective 4 in the out-of-focus clause;

-

prosodical marking by primary stress displacement from the verb stem to the initial syllable of the focused element;

-

only one term per clause can be syntactically and morphologically marked by the ex-situ construction; these are: subject and object NPs (or part of it), adverbials;

-

the ex-situ construction is used for assertive and contrastive focus alike (see also Diallo & Ermisch forth.).

Apart from the observation that the ex-situ term focus construction is bi-clausal, no deeper analysis on its structure has been made so far. In the next section I will discuss the possibility of its analysis as a cleft construction.

<21>

The ex-situ term focus construction presented in the previous section exists also in the Senegalese variety (the second line in example 14 illustrates the Guinean counterpart; the gloss is my own adaptation of this example):

|

(14) |

Focus on the time adverb |

||||||

|

Ko |

hannde |

Aali |

sood-i |

pucc-u |

ngu. |

(Senegal) |

|

|

Ko |

hannde |

Aali |

sood-i |

pucc-u |

ngun. |

(Guinea) |

|

|

t.foc |

today |

pn |

buy-a.pfv2 |

horse-10 |

def.10 |

||

|

ʻAli bought the horse TODAY.ʼ |

adapted from Sylla (1993:110) |

||||||

The only difference in the two examples consists in the different shape of the definite article.

Sylla (1993) claims for the Senegalese dialect that this construction type is a cleft sentence (‘clivé’) which is closely related to what he calls pseudo-clefts, interrogatives, relative and temporal sentences, all being subsumed under the term “emphatic constructions” (Sylla 1993:109-114). At first glance this assumption could be made for the Guinean dialect as well, as both sentences are identical regarding the focus clause and the out-of-focus clause. Taking this claim as a starting point, we should first define the term “cleft construction”. I follow Lambrecht (2001) in defining it as follows:

A CLEFT CONSTRUCTION (CC) is a complex sentence structure consisting of a matrix clause headed by a copula and a relative or relative-like clause whose relativized argument is coindexed with the predicative argument of the copula. Taken together, the matrix and the relative express a logically simple proposition, which can also be expressed in the form of a single clause without a change in truth conditions. (Lambrecht 2001:467)

<22>

Adopting this definition of a cleft, one would expect a relativized argument in the out-of-focus clause being coindexed with the head of the relative clause. Example (14) showed that the out-of-focus clause lacks such an argument. This raises the question of how a relative clause in Fulfulde of Fuuta Jaloo looks like and if the out-of-focus clause could fit to Lambrecht’s definition.

Sentences containing a relative clause (indicated by square brackets in the examples below) in Fulfulde of Fuuta Jaloo are characterized by four features: 1) the head noun of the matrix clause is definite, 2) the relative clause is inserted between the noun it modifies and its definite article, 3) the relative clause requires a relative pronoun and 4) the verb forms in the relative clause are restricted to the perfective 2 and imperfective 4. The examples (15) and (16) illustrate a subject and object relative:

|

(15) |

Subject relative |

|||||

|

Himo |

def-ude |

gerto-gal |

[sood-aa-ngal |

hanki] |

ngal. |

|

|

3s |

cook-a.prog |

chicken-11 |

[buy-pass.pfv2-rel.11 |

yesterday |

def.11 |

|

|

ʻS/He is cooking the chicken that was bought yesterday.ʼ |

(Evans 2001:76) |

|||||

|

(16) |

Object relative |

|||||

|

Nges-a |

[mba |

o |

rem-ata] |

mban |

njanɗ-aa. |

|

|

field-15 |

[rel.15 |

3s |

cultivate-a.ipfv4 |

def.15 |

be.big-a.pfv.neg |

|

|

ʻThe field that he cultivated is not big.ʼ |

(adapted from Diallo forthc.: 270) |

|||||

<23>

Similar to the enclitic subject pronouns described in section 3, the subject relative pronoun encliticizes to the finite verb in the perfective 2 or imperfective 4. When the verb of the relative clause is negated, the subject relative pronoun does not cliticize to it (note that the out-of-focus clause does not allow a negated verb form). In both subject and object relatives the relative pronoun is obligatory, in contrast to the Senegalese dialect where the relative pronoun in object relatives is optional (Sylla 1982).

There is no doubt that the out-of-focus clause resembles the relative clause, as both induce the same restriction to the verb forms which occur. But because of the absence of any argument in the out-of-focus clause referring to the focalized term, while “normal” relative clauses require such an argument (e.g. the relative pronoun), I claim that in the Guinean variety the ex-situ term focus construction is rather cleft-like than a real cleft according to Lambrecht’s (2001) definition.

In the next section, I will take a diachronic look on the construction and discuss two hypotheses for its development.

<24>

In the previous section I have argued that the ex-situ term focus construction in Fulfulde of Fuuta Jaloo cannot be analyzed synchronically as a cleft sentence. The presented similarities to “real cleft” constructions (in Lambrecht’s terms) still raise the question of an historic link between the two constructions.

At this point the grammaticalization theory represented by Heine & Reh (1983, 1984) who worked on African languages offers an explanation for the resemblances of clefts and assertive term focus constructions. Discussing similarities and differences of relative and out-of-focus clauses in languages such as Akan (Kwa < Niger-Congo), Kikuyu or Duala (both Bantu < Niger-Congo), the authors conclude that cleft constructions are the source of morphosyntactic term focus marking in these languages. In some cases these systems are identical to clefts; in others they are just similar. In order to capture the differences between the structures observed, two types of morphosyntactic term focus marking systems are distinguished: weakly and strongly grammaticalized systems. The categorization depends on the degree of grammaticalization.

The structure of ex-situ term focus in Fulfulde discussed above would be counted amongst the weakly grammaticalized systems. These are characterized by two features:

-

The surface properties of the focus itself witness to its derivation from a copular or identificational sentence functioning as matrix in the underlying structure. (Bearth 1999:125)

-

The part representing the presupposition – i.e., the out-of-focus part – shows some resemblance to dependent or more specifically to relative clauses. (ibid.)

The assumption is thus that the term focus construction is derived from a former cleft construction through a grammaticalization process. Adopting this hypothesis for the ex-situ term focus construction in Fulfulde of Fuuta Jaloo, this process would have taken place both in the focus clause and in the out-of-focus clause in three steps:

-

There is a cleft structure […] [which] serves to foreground new, asserted information, expressed by the sentence-initial constituent, the presupposed part of the sentence is encoded in the subordinate clause. (Heine & Reh 1983:36)

-

The copula is desemanticized as a focus marker. (ibid.)

-

The focus construction undergoes functional shift, i.e. it is no longer possible on synchronic grounds to derive it from the cleft construction, its source. (ibid.:36f.)

<25>

In order to apply the grammaticalization hypothesis to Fulfulde, let us look first at the focus clause. As described above, one can assume the grammaticalization of a copula sentence towards the focus clause. In Fulfulde this analysis is synchronically still transparent, as both lexemes – the copula (cop) and the term focus marker (tf) – are homophones, represented by the morpheme ko:

|

(17) |

Copula |

|||

|

Klaus |

ko |

almanjo. |

||

|

pn |

cop |

German |

||

|

ʻKlaus is German.ʼ |

(Diallo forthc.:44) |

|||

|

(18) |

Term focus marker |

||||

|

Ko |

jango |

o |

yah-ata. |

||

|

t.foc |

tomorrow |

3s |

go-a.ipfv4 |

||

|

ʻS/he will go TOMORROW.ʼ |

|||||

The function of both ko being different, they must be treated as distinct elements and thus be glossed differently. The grammaticalization path for the development of the term focus marker is illustrated in Figure 3 below:

|

Figure 3: Grammaticalization from copula to term focus marker |

||

|

Copula |

→ |

Term focus marker |

<26>

The second feature of a weakly grammaticalized system was said to be the resemblance between the out-of-focus clause and a dependent, i.e. relative clause. As I discussed in section 4, the similarity between ex-situ focus constructions and relative clauses consists in the restriction to the same verb forms used in both cases; the difference lies in the absence of the relative pronoun in the former. As described above, a cleft sentence according to Lambrecht (2001) would contain a relative pronoun in the out-of-focus clause while the verb form would not change. In a second step, the cleft construction grammaticalizes towards the ex-situ term focus construction. During this process, a) the copula is reanalyzed as term focus marker, b) the relative pronoun is deleted and c) the definite article of the focalized term precedes the out-of-focus clause:

|

(19) |

Cleft sentence |

||||||

|

*Ko |

gerto-gal |

[ngal |

ɓe |

hirs-i |

hanki] |

ngal. |

|

|

*cop |

chicken-11 |

[rel.1 |

3p |

slaughter-a.pfv2 |

yesterday |

def.11 |

|

|

ʻIt is the chicken that they slaughtered yesterday.ʼ |

|||||||

|

(20) |

Term focus construction |

||||||

|

Ko |

gerto-gal |

ngal |

∅ |

ɓe |

hirs-i |

hanki. |

|

|

t.foc |

chicken-11 |

def.11 |

3p |

slaughter-a.pfv2 |

yesterday |

||

|

ʻThey slaughtered THE CHICKEN yesterday.ʼ |

|||||||

The cleft sentence in example (19) is not attested today in the Fulfulde of Fuuta Jaloo and is thus marked as ungrammatical. Since cleft sentences inherently promote the clefted element, the grammaticalized cleft construction is naturally open for other terms such as adverbials to occur in the focus clause, although those cannot function as the head of a relative clause.

<27>

Comparing examples (19) and (20), the question arises what drove the deletion of the relative pronoun in the out-of-focus clause, while it remained in “normal” relative clauses. In fact, the deletion within relative clauses is excluded in Fulfulde of Fuuta Diallo, but in its close variety of Maasina (Mali) the relative pronoun and the final definite article are actually optional in object relatives, as shown in example (21a):

|

(21) |

Object relative clause |

|||||||

|

a. |

Maasina |

|||||||

|

Mi |

jang-ii |

defte-re |

[(nde) |

Demmba |

hokk-i-kam |

keenye] |

(nden). |

|

|

1s |

read-a.pfv3 |

book-5 |

[(rel.5 |

pn |

give-a.pfv2-1s |

yesterday |

def.5 |

|

|

b. |

Fuuta Jaloo |

|||||||

|

Mi |

jang-ii |

defte-re |

[nde |

Demmba |

okk-i-lan |

hanki] |

nden. |

|

|

1s |

read-a.pfv3 |

book-5 |

[rel.5 |

pn |

give-a.pfv2-1s |

yesterday |

def.5 |

|

|

ʻI read the book that Demmba gave me yesterday.ʼ |

(adapted from Gajdos 2004:107) |

|||||||

Example (21b) illustrates that both the relative pronoun and the definite article are not deletable in Fulfulde of Fuuta Jaloo, although the deletion itself is not an unusual behavior of relative pronouns in other Fulfulde dialects.

In this subsection, I demonstrated the possibility of the grammaticalization of a former cleft construction (which is no longer attested in the Fulfulde of Fuuta Jaloo) to the present-day ex-situ term focus construction, following cross-linguistic observations of Heine & Reh (1983, 1984). During the grammaticalization process the deletion of the relative pronoun took place while the verb form remained. Also the class of constituents functioning as focus was extended in contrast to those constituents functioning as the head of a relative clause. The resemblances between focus and relative constructions may, according to Heine & Reh (1983), be explained by the function of the two types, i.e. the promotion of a constituent from the embedded to the matrix clause, leading to a partly parallel but diachronically independent development (Heine & Reh 1983, Bearth 1999). In the next section I will discuss the idea that a cleft sentence is not necessarily the underlying form of the term focus construction.

<28>

As already foreshadowed above, it is also possible that not a cleft sentence is the source of the ex-situ term focus construction, but rather that the language reanalyzed for the focus clause and the out-of-focus clause other linguistic devices that already existed in the language. Here again, I want to examine both the focus clause and the out-of-focus clause separately.

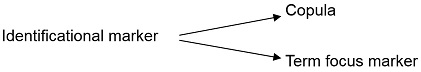

Instead of supposing that the term focus marker developed from a copula, another development could have taken place, as illustrated below:

|

Figure 4: From identificational marker to copula and term focus marker |

|

|

The identificational marker is homophonous to the copula and the term focus marker:

|

(22) |

Identificational marker |

|

|

Ko |

min! |

|

|

id |

1s.emph |

|

|

ʻIt’s me!ʼ |

||

Note that beyond the presented usages, ko is also used in other contexts, e.g. as a relative pronoun, making this morpheme highly polyfunctional in Fulfulde (for other usages see e.g. Diallo & Ermisch forth. or Evans 2001).

In example (22) we saw that the identificational marker ko identifies the following NP, directing the hearer’s attention towards the semantics of the latter representing thus the focal information:

|

(23) |

Identification |

|

|

[ko |

NP] |

|

|

[id |

Focus |

|

<29>

In an intermediate step, a topic preceded the identificational sentence before the structure became a normal copula sentence ([ko NP]→[Topic, ko NP]→[NP ko NP]) where the identificational marker is reanalyzed as a copula. On information-structural level, the first NP of a copula sentence is interpreted as the topic of the utterance, the information status of the NP preceded by the copula being higher, i.e. in focus:

|

(24) |

Copula |

||

|

NP |

[ko |

NP] |

|

|

Topic |

[id → cop |

Focus |

|

In examples (23) and (24), the morpheme ko promotes the following NP. The same happens in term focus constructions: in an intermediate step the identificational sentence is this time followed by a background clause ([ko NP] → [ko NP, background]). This became the ex-situ term focus construction [ko X background], where the identificational marker is reanalyzed as term focus marker. It promotes the term following it, preceding a background clause:

|

(25) |

Term focus |

||

|

[ko |

X] |

dependent clause |

|

|

[id → tf |

Focus |

Background |

|

The upper examples show that instead of assuming a former cleft construction, it is also possible that the resemblance between identificational and focus clause arises from the same function they share, i.e. promoting the following element. In term focus constructions this element is not necessarily a NP.

<30>

Evans (2001) supports the idea in seeing the basic function of ko in the identification: the ex-situ subject focus construction is also used for thetic utterances (also called all-new sentences or sentence focus), e.g. in the first sentence of a narration:

|

(26) |

Thetic utterance/Focus on the subject |

||||

|

Ko |

lan-ɗo |

tigg-u-noo |

rew-ɓe |

ɗiɗo. |

|

|

id/t.foc |

king-1 |

marry-a.pfv2-pret |

woman-2 |

two |

|

|

ʻ[What happened?] There was a king who had married two women.ʼ |

|||||

|

ʻ[WHO had married to women?] The KING had married two women.ʼ (ibid.:17) |

|||||

The meaning of example (26) is thus ambiguous between subject focus and a thetic utterance.

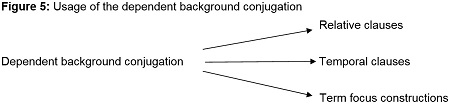

Let us now look again at the out-of-focus clause in the focus construction. Instead of assuming that the verb forms which are otherwise used in relative clauses entered in the term focus construction via a cleft, one could also imagine that the verb system possessed a conjugation which was restricted to dependent background clauses and which became used in different background contexts, as illustrated below:

|

|

<31>

The function of this conjugation pattern – i.e. the backgrounding of the respective clause towards the main clause – would provide a reasonable explanation for the fact that always the same verb forms are used in relative clauses (as described above), in temporal clauses and also in term focus constructions. On these grounds it is not surprising that the shared features of relative verbal forms and those used in term focus constructions are a widespread phenomenon, being mentioned e.g. for English (Germanic < Indo-European), Hausa (Chadic < Afro-Asiatic) or Ilongot (Malayo-Polynesian < Austronesian) (see Schachter 1973, Zima 2006).

The importance of this backgrounding function by the verb form is more striking in other dialects of Fulfulde which use a “reduced” structure to express term focus. There, only the backgrounding verb form together with the syntactic fronting are used for marking term focus. In both examples (27) from the Malian dialect of Maasina and (28) from the Nigerian dialect of Gombe, the adverbial stands sentence-initially without the term focus marker ko:

|

(27) |

Maasina: Focus on the location |

||

|

Segu |

njipp-ii-mi. |

||

|

pn |

get.out-midd.pfv2-1s |

||

|

ʻI got out (of the car) at SEGU.ʼ |

(Gajdos 2004:108) |

||

|

(28) |

Gombe: Contrastive focus on the adverb of time |

||||||

|

Hannde |

Bello |

wadd-i |

sheede |

(naa |

keenya). |

||

|

today |

pn |

bring-a.pfv2 |

money.3 |

(neg |

yesterday |

||

|

ʻBello brought money TODAY (not yesterday).ʼ |

(Arnott 1970:318) |

||||||

Especially the last two examples demonstrate the value of the backgrounding feature of the out-of-focus clause promoting inherently the focalized term of the matrix clause. Although the morphological marking of the background of an utterance instead of its focus part is a less frequently described strategy for term focus (see e.g. Bagirmi (Central Sudanic<Nilo-Saharan), Jacob 2010), its function helps to understand the resemblances of relative and out-of-focus clauses.

<32>

This present paper described the ex-situ term focus construction in Fulfulde of Fuuta Jaloo and took a synchronic and diachronic look at its bipartite structure. Synchronically, I reject the hypothesis of a cleft sentence as it is stated for the Senegalese dialect because a) the out-of-focus clause in the dialect of Fuuta Jaloo lacks a relative pronoun referring to the focalized term in the matrix clause and b) because of the out-of-focus clause which is not inserted between the focalized noun and its definite article as in sentences containing a relative clause. I claim that the structure is rather cleft-like. Diachronically, I discussed the hypothesis of a grammaticalization of a former cleft construction towards the present-day term focus structure. The assumption is threefold: the copula is grammaticalized to the term focus marker; the out-of-focus clause results from a relative clause which lost its relative pronoun during the grammaticalization process; the out-of-focus clause stands sentence-final regardless of the definite article of the focalized noun. The main idea of the second hypothesis targets the contexts in which both subclauses are used. According to this hypothesis, the identificational marker serves to draw the hearer’s attention to the following element and thus inherently focuses it. Regarding the out-of-focus clause, it was hypothesized that a former dependent background clause became used in relative clauses, temporal clauses and the out-of-focus clause in term focus constructions. All these construction types share the same function: backgrounding the respective clause towards its matrix clause.

As both hypotheses provide convincing arguments which overlap, none can be clearly preferred over the other one. But what is for sure today – and what is crucial for the analysis – is the observation that the verb forms merge not only information on tense/aspect/mood but also on voice and focus. As it was pointed out, the restriction of verb forms in out-of-focus clauses to those used for relative clauses is cross-linguistically a wide-spread phenomenon. Also, the verb forms used in backgrounding clauses are highly polyfunctional in Fulfulde as they also appear in narratives and are also used with stative verbs. Only a detailed analysis of the verb system as a whole can shed light on this language-specific distribution.

<33>

An interesting observation which is a good starting-point for further studies is that the focus clause also appears in different positions of the sentence: apart from the prototypical sentence-initial position demonstrated above, recordings of natural speech showed that the focus clause appears frequently between the subject and the verb:

|

(29) |

Gork-o |

on |

ko |

banaanaa-ru |

won-i |

ɲaam-ude. |

|

man-1 |

def.1 |

t.foc |

banana-7 |

exist-a.pfv2 |

eat-a.prog |

|

|

ʻ[What is the man eating?] The man is eating A BANANA.ʼ, |

||||||

One can analyze the subject as being topicalized (Lambrecht 2001), although the main clause lacks a trace of the extracted term, e.g. a subject pronoun. Structures as these have not been even mentioned yet for Fulfulde of Fuuta Jaloo, but are documented e.g. for the Senegalese variety. Focus clauses in Fulfulde of Fuuta Jaloo can also occur in the sentence-final position:

|

(30) |

Maria |

ko |

jog-ii |

ko |

sarii-re. |

|

pn |

pro? |

hold-midd.pfv2 |

t.foc |

rabbit-5 |

|

|

ʻ[What does Maria have, a rabbit or a cat?:] Maria holds a RABBIT.’ |

|||||

The analysis of the morpheme ko preceding the verb is less evident: possibly it could be interpreted as a pronoun, but the nature and function of this pronoun needs more investigation in the future. Structures like these are nearly not documented and their detailed analysis is left open for further research.

|

Abbreviations |

||||||||

|

a |

active voice |

midd |

middle voice |

prog |

progressive |

|||

|

cop |

copula |

np |

noun phrase |

pst |

past |

|||

|

def |

definite |

neg |

negative |

rel |

relative |

|||

|

emph |

emphatic |

pass |

passive voice |

s |

singular |

|||

|

foc |

focus |

pfv |

perfective |

t |

term |

|||

|

id |

identification |

pn |

proper name |

tam |

tense-aspect-mood |

|||

|

inf |

infinitive |

prep |

preposition |

vp |

verb phrase |

|||

|

instr |

instrumental suffix |

pret |

preterite |

* |

ungrammatical |

|||

|

ipfv |

imperfective |

pro |

pronoun |

1-15 |

number of agreement class |

|||

References

Anyanwu, Rose-Juliet and Abdourahmane Diallo 2005

'Rhythmic units and stress/Word accent mobility in Fula.' Frankfurter Afrikanistische Blätter 17:65-90

Arnott, David W. 1970

The nominal and verbal system of Fula. Oxford: Clarendon Press

Bao, Mingzhen 2012

'Prosody of focus among information structure in Pular.' Afrikanistik-Aegyptologie-Online, https://www.afrikanistik-aegyptologie-online.de/archiv/2012/3528 (15.01.2015)

Bearth, Thomas 1999

'The contribution of African linguistics towards a general theory of focus. Update and critical review.' Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 20:121-156

Diallo, Abdourahmane 2000

Grammaire descriptive du pular du Fuuta Jaloo (Guinée). Frankfurt am Main: Lang

Diallo, Abdourahmane, forthcoming

Lehrbuch des Pular. Nouvelles Etudes Guinéennes, Vol. I. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe

Diallo, Abdourahmane and Sonja Ermisch, forthcoming

'Konstituentenfokus im Fula des Fuuta Jaloo.' In: Voßen, Rainer (ed.) Frankfurter Afrikanistische Blätter. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe

Dik, Simon C. 1997

The theory of functional grammar, Part 1: The structure of the clause. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter

Evans, Barrie 2001

Teaching grammar of Pular. Christian Reformed World Missions

Fagerberg, Sonja 1983

'Discourse strategies in Pulaar: The use of focus.' Studies in African Linguistics 14,2:141-157

Fiedler, Ines, Katharina Hartmann, Brigitte Reineke, Anne Schwarz and Malte Zimmermann 2010

'Subject focus in West African languages.' In: Zimmermann, Malte and Caroline Féry (eds.) Information structure from different perspectives, pp.234-257. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Gajdos, Martina 2004

Fulfulde: Lehrbuch einer westafrikanischen Sprache. Wien: Edition Praesens

Harrison, Annette 2003

Fulfulde language family report. SIL Electronic Survey Reports 2003-009. http://www.sil.org/silesr/2003/silesr2003-009.html (28.02.2013)

Heine, Bernd and Mechthild Reh 1983

'Diachronic observations on completive focus marking in some African languages.' In: Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika 5:7-44

Heine, Bernd and Mechthild Reh 1984

Grammaticalization and reanalysis in African languages. Hamburg: Helmut Buske

Hyman, Larry M. and John R. Watters 1984

'Auxiliary Focus.' Studies in African Linguistics 15,3:233-273

Jacob, Peggy 2010

'On the obligatoriness of focus marking: Evidence from Tar B’arma.' In: Fiedler, Ines and Anne Schwarz (eds.) The Expression of Information Structure, pp.117-144. Amsterdam: Benjamins

Lambrecht, Knud 2001

'A framework for the analysis of cleft constructions.' Linguistics 39,3:463-516

Lewis, M. Paul (ed.) 2009 [2013]

Ethnologue: Languages of the world. Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. http://www.ethnologue.com/ (accessed 28.02.2013)

Robert, Stéphane 2010

'Focus in Atlantic languages.' In: Fiedler, Ines and Anne Schwarz (eds.) The expression of information structure, pp.233-260. Amsterdam: Benjamins

Schachter, Paul 1973

'Focus and relativization.' Language 49:19-46

Sylla, Yèro 1982

Grammaire moderne du pulaar. Dakar [et al.]: Les Nouvelles Éditions Africaines

Sylla, Yèro 1993

Syntaxe peule: contribution à la recherche sur les universaux du langage. Dakar: Les Nouvelles Éditions Africaines du Sénégal

Zima, Petr 2006

'Focus and focality as a grammatical category in the languages of West Africa.' Frankfurter Afrikanistische Blätter 18, pp.157-168

Zimmermann, Malte 2007

'Contrastive Focus.' In: Féry, C., G. Fanselow and M. Krifka (eds.) Interdisciplinary studies on information structure, Vol. 6: The notions of information structure, pp.147-159. Potsdam: Universitätsverlag

Lizenz

Empfohlene Zitierweise ¶

Apel V (2015). A synchronic and diachronic examination of the ex-situ term focus construction in Fulfulde of Fuuta Jaloo. Afrikanistik-Aegyptologie-online, Vol. 2015. (urn:nbn:de:0009-10-41558)

Bitte geben Sie beim Zitieren dieses Artikels die exakte URL und das Datum Ihres letzten Besuchs bei dieser Online-Adresse an.

Volltext ¶

-

Volltext als PDF

(

Taille

709.5 kB

)

Volltext als PDF

(

Taille

709.5 kB

)

Kommentare ¶

Es liegen noch keine Kommentare vor.

Möchten Sie Stellung zu diesem Artikel nehmen oder haben Sie Ergänzungen?

Kommentar einreichen.