Language attitudes and language shift among ethnic migrants in Khartoum [1]

urn:nbn:de:0009-10-1814

Abstract

This paper investigates language attitudes among ethnic migrant groups in Khartoum, the capital city of Sudan. A questionnaire was used to collect data on language preference, language parents prefer their children to learn, and reasons for language preference. Results suggest that while positive attitude played a significant role in learning Arabic among some of the groups under investigation, it proved to be of no help in maintaining the groups’ ethnic languages. Arabic was reported as very important for education, religious activities, economic privileges and social interaction. Ethnic languages, on the other hand, were preferred for purely symbolic reasons (symbolizing groups’ ethnic identity).

Résumé

Cet article examine le comportement linguistique de certains groupes ethniques d’immigrés à Khartoum, la capitale du Soudan. A l’aide d’un questionnaire on a collecté des données sur les langues utilisées de préférence et sur celles que les parents aimeraient que leurs enfants apprennent et pour quels domaines telle ou telle langue est préférée. Les résultats laissent entrevoir qu’une attitude pos4itive à l’égard de l’arabe n’est pas favorable au maintien des langues des groupes ethniques. On accorde une grande importance à l’arabe dans l’éducation et la formation, dans la religion, dans les activités économiques et dans les contacts sociaux. Les langues des groupes ethniques n’ont qu’une valeur symbolique (elles sont le symbole de l’identité ethnique du groupe).

Zusammenfassung

Die Arbeit untersucht Spracheinstellungen bei Gruppen ethnischer Migranten in Khartum, der Hauptstadt des Sudan. Mittels eines Fragenkatalogs wurden Angaben darüber erhoben, welche Sprachen bevorzugt benutzt werden, von welchen es wichtig erscheint, dass die Kinder sie lernen, und für welche Domänen welche Sprachen bevorzugt werden. Die Ergebnisse deuten an, dass eine positive Einstellung gegenüber dem Arabischen, dem Erhalt der ethnischen Sprachen nicht förderlich ist. Dem Arabischen wird eine große Bedeutung in der Erziehung/Ausbildung, der Religion, wirtschaftlichen Vorteilen und im gesellschaftlichen Austausch zugeschrieben. Den ethnischen Sprachen, wird dagegen nur symbolische Bedeutung zugemessen, als Symbol der ethnischen Identität der Gruppe.

<1>

As language constitutes an integral part of society and individuals’ identity, people’s attitudes towards it must have strong effects on its status within a given community. Gardner and Lambert's (1972) study of language attitude, commonly accepted as systematic attempts in the field of language teaching and learning, propose motivation as a construct made up of specific attitudes to language. The most important of these is group-specific; the attitude learners have towards the members of the cultural group whose language they are learning. In this context, a vernacular speaker’s positive attitude towards Arabic language and culture, for instance, will help him/her formulate a strong motivation to learn Arabic. In such cases, the language learner is thought to have integrative motivation. Other learners may be interested in learning a language just because they want to achieve certain objectives through it. These are believed to have instrumental motivation (ibid). It is this kind of motivation that plays an increasing role in leading vernacular-speaking immigrants to learn the dominant language in the host environment.

<2>

According to Adegbija (1994), many Africans view their own ethnic languages as unsuitable for use in official domains. They believe that these languages lack the capacity for expressing ideas in a variety of domains. As a result, indigenous languages were excluded from all aspects of communication in official settings. The neglect experienced by these languages played a significant role in creating a negative attitude towards them, which may lead to their demise in the future. To counter this situation, language revival strategies and procedures are desperately needed. As most indigenous languages are not written, standardization and graphitization could be of a great help. A graphitized language potentially receives the power to recreate, reproduce and advertise itself in a new way. A non-graphitized language, on the other hand, tends to maintain only a local essence and existence (Adegbija 1992). Standardization and graphitization, then, can help develop positive attitudes towards indigenous languages.

<3>

The need for a positive attitude towards indigenous languages requires an active involvement of governments in the affected areas. As governments in many parts of the world apparently prefer the existence of a single unifying language, chances for the survival of indigenous languages are limited. Arabicization of education in the Sudan, for instance, represents a serious danger to the country’s rich linguistic diversity. This is because the use of Arabic as a medium of instruction in schools and universities further enhances the neglect of indigenous languages and consequently creates more negative attitudes to them. However, the Naivasha Peace Protocol signed by the government of the Sudan and the Sudan’s People Liberation Movement in 2004 may play a very important role in changing people’s attitude towards the country’s rich linguistic resources. The accord clearly states that all Sudanese languages are national languages worthy of respect, promotion and development (IGAD 2004). However, practical steps aiming at putting these recommendations into practice are yet to appear.

<4>

This paper investigates language attitude among migrant ethnic minority groups in Khartoum, the capital city of the Sudan. The prime objective of the paper is to see whether language attitude plays a role in the process of language maintenance and shift among these groups. Language attitude is defined by Richards et al. (1985) as the feeling that speakers of different languages or varieties of a language have towards each others’ languages or their own. Negative or positive attitude towards a language may reflect linguistic difficulty or simplicity of learning, degree of importance and social status. Fasold (1987) differentiates language attitude from other attitudes in that language attitude is precisely about language. In studying language attitude, respondents are asked to report if they think a given language or variety is ‘rich’, ‘poor’, ‘important’, ‘beautiful’, ‘ugly’, ‘sweet sounding’, ‘harsh’ and so on. Further, the definition of language attitude is extended to cover the way in which language is dealt with in a variety of domains including language maintenance and planning efforts (ibid).

<5>

Khartoum has been selected because of its cosmopolitan nature. People from different parts of the Sudan constitute its more than 7 million population. Migration to the city was particularly intensified by the outbreak of war in the southern region of the Sudan and the Nuba Mountains as well as drought and desertification in Darfur in the mid 1980s. Arabic is the dominant language in Khartoum. It plays the role of the lingua franca among its linguistically diverse inhabitants. In addition, Arabic is the language of communication in government institutions, hospitals, schools, universities and work places.

<6>

According to Fasold (1987), methods for determining subjects’ attitudes about language can be direct or indirect. A typically direct method requires subjects to state their opinions about a given language in reply to a questionnaire or interview questions that simply ask about their feeling toward a language or another. A totally indirect method could be one in which the subjects are unaware of the fact that their language attitude is being tested. Given the relatively big number of the target population, the researcher chose the first method. Accordingly, a questionnaire was distributed to the subjects in schools, universities, work places, neighborhoods and houses. The questionnaire was divided into two parts. In the first part, subjects were asked to list the languages they like best and to identify the reasons behind their choice. Five options were offered: educational, economic, social interaction, religious and symbolic (symbols for group’s ethnic identity) reasons. In the second part, only older generation respondents were requested to answer questions about the languages they would like their children to learn and to justify their choice (educational, economic, social interaction, religious and symbolic reasons).

<7>

The total number of respondents is 840 drawn from 14 ethnic groups: Nobiin, Kenzi-Dongolese, Beja, Dinka, Shilluk, Viri, Madi, Gulfan, Nyimang, Miri, Zaghawa, Fur, Massalit, and Daju. These groups were selected purposely to form some sort of geographic representation for the Sudanese languages. Thus, the eastern part of Sudan was represented by Beja, the South by Dinka, Shilluk, Viri, and Madi, the Nuba Mountains By Gulfan, Nyimang, and Miri, Darfur by Zaghawa, Fur, Massalit, and Daju, and the North by Nobiin and Kenzi-Dongolese. The respondents belong to three age groups: children, youth and adults. Respondents of the first age group were selected randomly from the three towns constituting Greater Khartoum: Khartoum, Khartoum North, and Omdurman. Most of them were primary and secondary schools pupils. Their overall number was 280 (20 respondents from each language group) and their age ranged between 10 to 19 years old. The schools in which these subjects were enrolled usually follow the Ministry of Education syllabus in which Arabic is used as a medium of instruction as well as a subject. The second group of respondents consists of university students, civil service employees, soldiers, workers, etc. They were 280 subjects representing the fourteen language groups examined (20 respondents from each language group). Their age ranged between 20 to 39 years old. The third group of respondents was also selected randomly from different areas in Greater Khartoum and occupational backgrounds (teachers, soldiers, physicians, merchants, farmers, housewives, etc,). They were 280 and their age ranged between 40 years and above. It is important to note that this group included subjects from different educational backgrounds ranging from primary to university level. Most of the educated ones had received their education in Arabic.

<8>

The SPSS program (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) was used to analyze answers to the questions on language attitude. Frequency and Chi-square test were employed in the process.

<9>

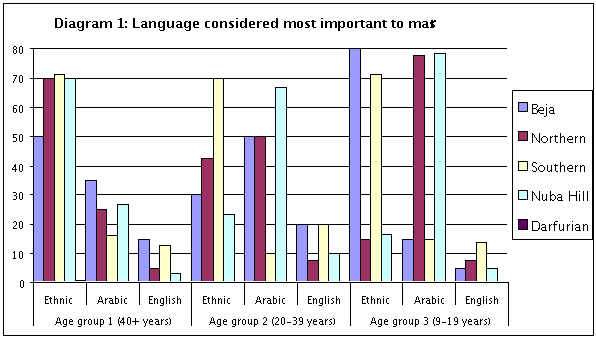

Table 1b shows that 42.78% of the entire population investigated reported that Arabic was their preferable language. In contrast, 9.28% of the population claimed that they preferred English more than other languages. This means that local languages are preferred by less than 48% of the respondents. It seems that the predominant role of Arabic in the area has decreased positive attitude towards ethnic languages as vernacular-speaking communities actually use more Arabic than their own languages in most domains of communication. Similar findings were reported by Miller and Abu Manga (1992) when they studied language maintenance and attitude in Altakamul displace camp in Khartoum North.

<10>

The table also shows that language preference differs significantly from the first to the third group. For the first group, 31.78% and 7.5% reported that they preferred to speak Arabic and English, respectively. In other words, only 60.72% of the ethnic minority older generations preferred speaking their ethnic languages. Positive attitudes towards ethnic mother tongue, then, was found among 71.25% of the Southern group, 70% of the Northern group, 70% of the Nuba Hills, 50%of the Beja and 41.25% of the Darfurian. These results, when compared to the use of language by these people seem to suggest that the extent to which ethnic languages are used can not be taken as evidence for language loyalty among these groups. That is, most minority language communities tend to use the dominant language in the host environment in spite of the fact that they claimed that they preferred to speak their own languages. The general picture, however, indicates a significant tendency to language shift among vernacular-speaking older generations.

<11>

For the second group the proportion of those preferring to speak Arabic and English increases to 40.71% and 12.5%, respectively. Compared to what happened in the first group, loyalty to the ethnic language decreases to about 46.79%. This figure is distributed among 30% of the Beja, 42.5% of the Northern group, 70% of the Southern group, 23.33% of the Nuba Hills and 47.5% of the Darfurian. If these percentages are correlated to the language actually used by the second group respondents, a significant tendency to language shift towards Arabic can be obviously observed. This suggests that, except for the southerners, Arabic is being highly valued among younger generation members of ethnic minority groups in Khartoum.

<12>

Among the third group the proportion of ethnic language preference decreases remarkably. 55.71% and 7.85% of this group reported that they preferred to speak Arabic and English, respectively. This means that only 36.44% of the third group respondents were loyal to their own ethnic languages. However, loyalty to the ethnic languages appeared to have been pronounced among the Beja (80%), and the Southerners (71.25%). These two groups are, in fact, highly conscious of their own ethnic and cultural identity. They tend to signal their ethnic affiliation by using their ethnic languages whenever language choice is available for them in a given context. The table also shows that while strong language loyalty among the southerners is consistent across the different age groups, it proved to be remarkably inconsistent among the Beja. That is, while a vas majority of the third age group (80%) reported that they preferred the ethnic language, only 30% of the second age group and 58% of the third age group claimed that they did so. This is simply because members of the two latter groups, are more conscious of the importance of Arabic in practical domains such as education, social interaction, and religion (see Table 4- reasons for language preference).

Table 1a: Language considered most important to master (respondents in numbers)

|

Age group 1 (40+ years) |

Age group 2 (20-39 years) |

Age group 3 (9-19 years) |

|||||||||||

|

Ethn. |

Ar. |

Engl. |

Subtotal |

Ethn. |

Ar. |

Engl. |

Subtotal |

Ethn. |

Ar. |

Engl. |

Subtotal |

Total |

|

|

Beja |

10 |

7 |

3 |

20 |

6 |

10 |

4 |

20 |

16 |

3 |

1 |

20 |

60 |

|

Northern |

28 |

10 |

2 |

40 |

17 |

20 |

3 |

40 |

6 |

31 |

3 |

40 |

120 |

|

Southern |

57 |

13 |

10 |

80 |

56 |

8 |

16 |

80 |

57 |

12 |

11 |

80 |

240 |

|

Nuba Hills |

42 |

16 |

2 |

60 |

14 |

40 |

6 |

60 |

10 |

47 |

3 |

60 |

180 |

|

Darfurian |

33 |

43 |

4 |

80 |

38 |

36 |

6 |

80 |

13 |

63 |

4 |

80 |

240 |

|

Total |

170 |

89 |

21 |

280 |

131 |

114 |

35 |

280 |

102 |

156 |

22 |

280 |

840 |

Table 1b: Language considered most important to master (respondents in %)

|

Age group 1 (40+ years) |

Age group 2 (20-39 years) |

Age group 3 (9-19 years) |

||||||||

|

Ethnic |

Arabic |

English |

Ethn. |

Ar. |

Engl. |

Ethn. |

Ar. |

Engl. |

||

|

Beja |

50 |

35 |

15 |

30 |

50 |

20 |

80 |

15 |

5 |

|

|

Northern |

70 |

25 |

5 |

42.5 |

50 |

7.5 |

15 |

77.5 |

7.5 |

|

|

Southern |

71.25 |

16.25 |

12.5 |

70 |

10 |

20 |

71.25 |

15 |

13.75 |

|

|

Nuba Hills |

70 |

26.67 |

3.33 |

23.33 |

66.67 |

10 |

16.67 |

78.33 |

5 |

|

|

Darfurian |

41.25 |

53.75 |

5 |

47.5 |

45 |

7.5 |

16.25 |

78.75 |

5 |

|

|

Total |

60.71 |

31.79 |

7.5 |

46.79 |

40.71 |

12.5 |

36.43 |

55.71 |

7.86 |

|

Diagram 1: Language considered most important to master

<13>

In this section, we will investigate the language that ethnic group members like their children to learn. Such an analysis will give a clear picture of the future of ethnic languages in Khartoum. This is because if parents find it necessary for children to learn the group’s language, they will spare no effort to achieve this goal and consequently chances for ethnic languages to survive will be higher. Tables 2a and 2b give the distribution of language respondents’ preference for children to speak.

Table 2a: Language considered most important for children to learn (in absolute numbers)

|

Age group 1 (40+ years) |

Age group 2 (20 – 39 years) |

|||||||||

|

Ethnic |

Arabic |

Engl. |

Subtotal |

Ethnic |

Arabic |

Engl. |

Subtotal |

Total |

||

|

Beja |

5 |

11 |

4 |

20 |

8 |

7 |

5 |

20 |

40 |

|

|

Northern |

8 |

26 |

6 |

40 |

10 |

26 |

4 |

40 |

80 |

|

|

Southern |

64 |

6 |

10 |

80 |

58 |

10 |

12 |

80 |

160 |

|

|

Nuba Hills |

13 |

42 |

5 |

60 |

12 |

41 |

7 |

60 |

120 |

|

|

Darfurian |

36 |

39 |

5 |

80 |

36 |

38 |

6 |

80 |

160 |

|

|

Total |

126 |

124 |

30 |

280 |

124 |

122 |

34 |

280 |

560 |

|

Table 2b: Language considered most important for children to learn (in %)

|

Age group 1 (40+ years) |

Age group 2 (20 – 39 years) |

|||||

|

Ethnic |

Arabic |

English |

Ethnic |

Arabic |

English |

|

|

Beja |

25 |

55 |

20 |

40 |

35 |

25 |

|

Northern |

20 |

65 |

15 |

25 |

65 |

10 |

|

Southern |

80 |

7.5 |

12.5 |

72.5 |

12.5 |

15 |

|

Nuba Hills |

21.67 |

70 |

8.33 |

20 |

68.33 |

11.67 |

|

Darfurian |

45 |

48.75 |

6.25 |

45 |

47.5 |

7.5 |

|

Total |

45 |

44.29 |

10.71 |

44.29 |

43.57 |

12.14 |

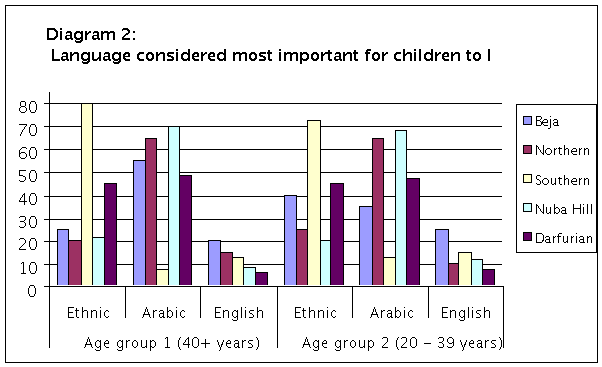

Diagram 2: Language considered most important for children to learn

<14>

Table 2b shows that 43.92% of both the first age group and the second age group reported that they liked to see their children speak Arabic. Preference of local vernaculars and English, on the other hand, was found among 44.5% and 11.5% of the sample, respectively. The figures suggest that about 56% of both age groups did not see learning of vernaculars as a top priority for their children. The table also shows that parents from the southern group reported the highest rate of ethnic language preference for children (70%). This is because members of this group are very proud of their own ethnic and cultural identity. They tend to identify with their language as an effective mechanism of maintaining their ethnic traditions. Positive attitude towards ethnic language, among the remaining age groups, on the other hand, has been observed with almost the same degree of significance. Over 43% of the second group and 44% of the first group wanted their children to speak Arabic. Moreover, over 12% of the second age group and about 11% of the first age group reported that they wanted their children to speak English. This means that only 45% of the second group and 44% of the first group supported local vernacular maintenance for ideological and symbolic reasons. This tendency was registered by 44% of the sample distributed as follows: 40% of the Beja, 25% of the Northern group, 75.5% of the Southern group, 20% of the Nuba Hills, and 45% of the Darfurian. In contrast, 45% of the third group supported maintenance of their languages by indicating the necessity of mastering vernaculars on the part of their children. This claim was found among 5 informants of the Beja (25%), 8 informants of the Northern group (20%), 64 informants of the Southern group (80%), 13 informants of the Nuba Hills (21.66%), and 36 informants of the Darfurian (45%). Again, the southern group took the lead in ethnic language preference.

<15>

In this section of our analysis of language attitude, we are going to investigate the reasons behind preferring a certain language by the population under study. Tables 3a and 3b give the reasons for language preference according to age.

Table 3a: Domains determining language choice (in numbers, 280 respondents per age group)

|

Age group 1 (40+ years) |

Age group 2 (20-39 years) |

Age group 3 (9-19 years) |

||||||||

|

Domains |

Arabic |

Ethnic |

English |

Arabic |

Ethnic |

English |

Arabic |

Ethnic |

English |

|

|

Educational |

56 |

51 |

93 |

98 |

142 |

81 |

||||

|

Social |

86 |

93 |

59 |

|||||||

|

Economic |

10 |

2 |

5 |

24 |

23 |

|||||

|

Religious |

62 |

26 |

29 |

|||||||

|

Symbolic |

219 |

217 |

176 |

|||||||

|

Total |

214 |

219 |

53 |

217 |

217 |

122 |

230 |

176 |

104 |

|

Table 3b: Domains determining language choice (in %)

|

Age group 1 (40+ years) |

Age group 2 (20-39 years) |

Age group 3 (9-19 years) |

||||||||

|

Domains |

Ar. |

Ethn. |

Engl. |

Ar. |

Ethn. |

Engl. |

Ar. |

Ethn. |

Engl. |

|

|

Educational |

20 |

18.21 |

33.21 |

35 |

50.71 |

28.93 |

||||

|

Social |

30.71 |

33.21 |

21.07 |

|||||||

|

Economic |

3.57 |

0.71 |

1.79 |

8.57 |

8.21 |

|||||

|

Religious |

22.14 |

9.29 |

10.36 |

|||||||

|

Symbolic |

78.21 |

77.5 |

62.86 |

|||||||

|

Total |

76.43 |

78.21 |

18.93 |

77.5 |

77.5 |

43.57 |

82.14 |

62.86 |

37.14 |

|

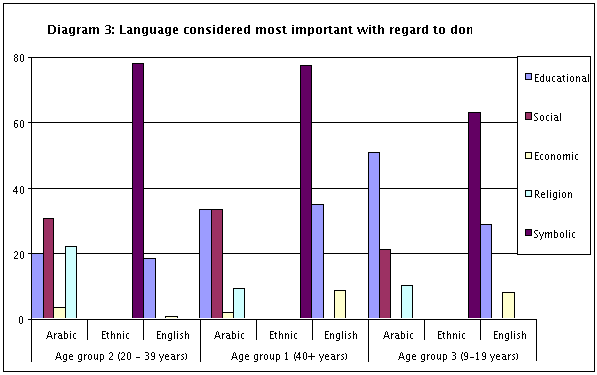

Diagram 3: Language considered most important with regard to domains

<16>

Table 3b shows that 76.43% of the first group, 77.5% of the second group and 82.14% of the third group reported that they preferred to speak Arabic. Preference of Arabic was attributed to five components: educational, social, economic, religious and symbolic (symbolizing group's ethnic identity). In other words, Arabic has been classified as an important language on the basis of the greater role it plays in the social economic and religious aspects of minority groups' everyday life. Ethnic languages, on the other hand, were preferred by 78% of the first age group, 77% of second age group and 62% of the third age group for symbolic reasons. This is a clear indication of the role of ethnic languages in the life of their immediate communities is relatively limited.

<17>

The table also shows that the distribution of the five attitude components towards Arabic and English differs significantly from the first to the third generation. For the first generation, Arabic was reported by 20% for educational reasons, 30% for social reasons, 10% for economic reasons, and 10.3% for religious reasons. If we add up those who prefer English for different reasons, (18.2 for education and 0.7% of economic reasons), we will come to the conclusion that almost 80% of this age group do not see their ethnic languages as playing practical roles in their daily life.

<18>

A very interesting observation to be made from this stratification is that the proportion of Arabic preference increases significantly from the second age group to the first one. Over 33% of the second group respondents reported that they preferred Arabic because it was the language of education. Furthermore, 33% preferred Arabic for social interaction, 1.7% for economic reasons, and 9% for religious purposes. This means that about 76% of this group viewed Arabic as a very important instrument for meeting their everyday life needs. English on the other hand, was preferred by 35% for educational reasons and by 8.5% for economic reasons. This is a clear indication that Arabic and English constitute the prime concern of the second-generation ethnic minority groups' future plans and perspectives, which negatively influences the status and maintenance of ethnic languages.

<19>

Attitude to Arabic among younger generation respondents as shown by Tables 3a and 3b seems to have three major components. The first of these is educational: ‘I would like to speak Arabic because Arabic is the language of education’. Such statements were reported by over 50% of the third group respondents. The second component is social represented by statements such as (‘‘would like to speak Arabic because it enables me to communicate with others’’), (‘‘Arabic is the language of communication’’), etc. Such statements were reported by 21% of the third age group. The third attitude component is religious in nature: (‘‘Arabic is the language of Islam’’), (‘‘I would like to speak Arabic because Arabic is the language of the holy Qur'an’’), (‘‘Arabic should be spoken because it the symbol of Muslim nationhood’’) reported by over 10% of the same age group. Preference of Arabic for religious purposes appears to have increased from the first age group to the third one. This indicates that young generation respondents are less concerned with religion compared to their old counterpart. Positive attitude to English, on the other hand, was reported by about 29% and 8% of the group for educational and economic reasons, respectively. The existence of such a positive attitude to Arabic and English coupled with a relatively negative attitude to the ethnic languages among young generation members of ethnic minority groups suggests that the groups in question are more prone to language shift.

<20>

One of the most interesting features of bilingualism among the subjects of this study is the obvious discrepancy between the verbal responses measuring attitude towards local languages and the actual linguistic behavior of the population. That is, while a considerable number of these people reported they preferred using ethnic languages in all domains of communication, they actually used Arabic more than ethnic languages in most of these domains. This tendency can be also reflected by the language they prefer for their children to learn. Tables 4a and 4b give parental attitudes towards the languages they want children to learn.

Table 4a: Language considered most important for children to learn with regard to domain (in absolute numbers)

|

Age group 1 |

Age group 2 |

|||||

|

(40+ years, 280 respondents) |

(20-39 years, 280 respondents) |

|||||

|

Domain |

Arabic |

Ethnic |

English |

Arabic |

Ethnic |

English |

|

Educational |

129 |

111 |

138 |

114 |

||

|

Social |

35 |

31 |

||||

|

Economic |

66 |

45 |

||||

|

Religion |

42 |

57 |

||||

|

Heritage |

215 |

221 |

||||

|

Total |

206 |

215 |

177 |

226 |

221 |

159 |

Table 4b: Language considered most important for children to learn with regard to domain (in %)

|

Age group 1 |

Age group 2 |

|||||

|

(40+ years, 280 respondents) |

(20-39 years, 280 respondents) |

|||||

|

Domain |

Arabic |

Ethnic |

English |

Arabic |

Ethnic |

English |

|

Education |

46.07 |

39.64 |

49.29 |

40.71 |

||

|

Social |

12.5 |

11.07 |

||||

|

Economic |

23.57 |

16.07 |

||||

|

Religious |

15 |

20.36 |

||||

|

Heritage |

76.79 |

78.93 |

||||

|

Total |

73.57 |

76.79 |

63.21 |

80.71 |

78.93 |

56.79 |

<21>

Inspection of Table 4a and 4b shows that both first and second group respondents have reported similar attitudes to the three languages they specified as being very important for their children to learn. Preference of Arabic, vernaculars and English was reported by 73.57%, 76.78% and 63.21% of the second group, respectively. All three languages were reported as very important for children by 80.07%, 78.92% and 56.71% of the first group, respectively. These figures when compared with mother tongue retention among the young generation, suggest that a significant discrepancy exists between parents' verbal statement regarding ethnic mother tongue preference for their children and the actual language behavior of the children. In other words, while about 77% of the second group and 80% of the first group reported that they preferred to see their children speak ethnic languages, a considerable number of the children have already adopted Arabic as a mother tongue.

<22>

However, attitudes to the three languages were found to have more than one component. Among the first group respondents, the first factor, education, was reported by 49.28% in favor of Arabic and 40.07% in favor of English. The second factor, social interaction, was reported by 11.07% in favor of Arabic and the third factor, economic importance, was reported by 16.07% in favor of English. Religion and ethnic traditions, on the other hand, were reported by 20.35% in favor of Arabic and 76.78% in favor of ethnic languages, respectively. The figures suggest that while Arabic was viewed as very important for education, social interaction and economic privileges, the importance of vernaculars was limited to ethnic traditions. Since urban life in Khartoum requires extensive use of Arabic, parents have to accept the fact that their children have to use the language in all domains of communication except the home, where use of ethnic languages is encouraged to emphasize the groups' identity.

<23>

Among the second age group language preference for children seems to follow almost the same pattern compared to what happened in the first age group. Arabic and English were reported as preferable for educational reasons by 46.07% and 40.07%, respectively. The second and third factors 'social communication and religious purposes' were ascribed to Arabic by about 12.5% and 15%, respectively. In contrast, the third factor 'economic importance' was ascribed to English exclusively by 23.57% of the second group respondents. This indicates that while second group parents wished to see their children speaking vernaculars for the sake of maintaining the group’s cultural and linguistic heritage, they did visualize Arabic and English as very important keys to education, economic interests, social interaction with other groups, and religious activities. As a consequence, parents have to encourage their children to learn the two languages at the expense of ethnic languages which apparently have no role to play in their socio-economic life.

<24>

The data also indicate that preference of a language in a given domain differs significantly across the age groups. This can be summed up in a few points. First, we find a more consistent and repeated favoring of Arabic and English for education among the old generations. This is mainly because old people are particularly concerned about securing education for their children. Second, with respect to religion, preference of Arabic by the old generation is higher than that among young generations. That is, as people advance in age they tend to be more religious than they are during their youth. Third, the greatest degree of preference of English for economic privileges is found among the younger generations. This is because while young generations look forward to getting better job opportunities, old people approach retirement. Since English is always viewed as a key to better job opportunities, it may be logical to assume that it will be the major concern of younger generations. Fourth, old generation respondents slightly surpass their young counterparts in favoring ethnic languages, which indicates that ethic language loyalty is stronger among the old generation speakers of ethnic languages.

<25>

In this section we are going to investigate whether there is a significant relationship between positive attitude towards a language and its mastery as a mother tongue. To this end, the chi-square test has been employed to process data on subjects' verbal responses about the languages they like best and that they speak natively. This procedure will be adopted across the three age groups studied.

<26>

Tables 5a and 5b give the relationship between language attitude and mother tongue maintenance among the first age group.

Table 5a: Language attitude and mother tongue maintenance by the first age group (40+ years, 280 respondents)

|

Mother tongues of respondents |

||||||||

|

Preferred language |

Arabic |

Beja |

Northern |

Southern |

Nuba Hills |

Darfurian |

Others |

Total |

|

Arabic |

126 |

2 |

2 |

9 |

4 |

9 |

4 |

156 |

|

Beja |

7 |

9 |

16 |

|||||

|

Northern |

6 |

6 |

||||||

|

Southern |

16 |

41 |

57 |

|||||

|

Nuba Hills |

6 |

4 |

10 |

|||||

|

Darfurian |

12 |

1 |

13 |

|||||

|

Others |

15 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

22 |

|||

|

Total |

188 |

11 |

2 |

53 |

8 |

12 |

6 |

280 |

Table 5b: Language attitude and mother tongue maintenance by the first age group (40+ years, 280 respondents)

|

Mother tongues of respondents |

||||||||

|

Preferred language |

Arabic |

Beja |

Northern |

Southern |

Nuba Hills |

Darfurian |

Others |

Total |

|

Arabic |

45 |

18.18 |

100 |

16.98 |

50 |

75 |

66.67 |

55.71 |

|

Beja |

2.5 |

81.82 |

5.71 |

|||||

|

Northern |

2.14 |

2.14 |

||||||

|

Southern |

5.71 |

77.36 |

20.36 |

|||||

|

Nuba Hills |

2.14 |

50 |

3.57 |

|||||

|

Darfurian |

4.29 |

8.33 |

4.64 |

|||||

|

Others |

5.36 |

5.66 |

16.67 |

33.33 |

7.86 |

|||

|

Total |

67.14 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

<27>

Table 5b shows that a significant relationship exists between language attitude and mother tongue shift among members of the first age group. The relationship was found with chi square < 174.50; df 36 and significance value .00000, in that a significant correlation was found between mastery of Arabic as a mother tongue and positive attitude towards the language. Moreover, unlike the rest of the groups, respondents from the Nuba Mountains have shown a significant discrepancy between positive attitude towards Arabic and ethnic language retention. While they reported mastery of ethnic language natively, they did prefer to speak Arabic. Conversely, Darfurian children displayed a significant association between mastery of Arabic as a mother tongue and positive attitude towards vernaculars. This suggests that these individuals are consciously aware of the threat to the survival of their own languages. They are, however, unable to do anything about it, given the practical reality of the language situation in Khartoum, which tends to favor Arabic rather than the ethnic languages. The speakers of minority languages are unwilling to lose their languages; but they also need to get access to the socioeconomic benefits associated with the mastery of Arabic in the country in general and Khartoum in particular.

<28>

The table also shows that the existence of a significant association between positive attitude towards ethnic languages and their mastery as mother tongues was found to have been prevalent among the Southern and the Beja groups. This is because the two groups highly value their languages as important symbols of ethnic identity, which helps them maintain the ethnic languages longer. Positive attitude, then, enhances the efforts made by language activist groups to use minority languages in a number of domains, and this helps people resist the enormous pressures placed on them to shift to the dominant language.

<29>

Tables 6a and 6b give the relationship between language attitude and mother tongue maintenance among members of the second group.

Table 6a: Language attitude and mother tongue maintenance among group 2 (20 – 39 years, 278 respondents, in absolute numbers)

|

Mother tongues of respondents |

||||||||

|

Language preferred |

Arabic |

Beja |

Northern |

Southern |

Nuba Hills |

Darfurian |

Others |

Total |

|

Arabic |

69 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

14 |

13 |

2 |

112 |

|

Beja |

2 |

4 |

6 |

|||||

|

Northern |

5 |

12 |

17 |

|||||

|

Southern |

11 |

45 |

56 |

|||||

|

Nuba Hills |

11 |

3 |

14 |

|||||

|

Darfurian |

21 |

|

17 |

38 |

||||

|

Others |

20 |

4 |

1 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

35 |

|

Total |

139 |

13 |

17 |

56 |

19 |

31 |

3 |

278 |

Table 6b: Language attitude and mother tongue maintenance among group 2 (20 – 39 years, 278 respondents, in %)

|

Mother tongues of respondents |

||||||||||

|

Arabic |

Beja |

Northern |

Southern |

Nuba Hills |

Darfurian |

Others |

Total |

|||

|

Language |

49.64 |

38.46 |

23.53 |

8.93 |

73.68 |

41.94 |

66.67 |

40.29 |

||

|

Beja |

1.44 |

30.77 |

2.16 |

|||||||

|

Northern |

3.6 |

70.59 |

6.12 |

|||||||

|

Southern |

7.91 |

80.36 |

20.14 |

|||||||

|

Nuba Hills |

7.91 |

15.79 |

5.04 |

|||||||

|

Darfurian |

15.11 |

54.84 |

13.67 |

|||||||

|

Others |

14.39 |

30.77 |

5.88 |

10.71 |

10.53 |

3.23 |

33.33 |

12.59 |

||

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

<30>

Tables 6a and 6b show that a significant relationship was present between mother tongue retention and language preference among members of the second age group. The relationship was present with Chi square = 402.22127, df= 32, p.00000, in that a strong relationship was found between mastery of a language as a mother tongue and its preference as a primary language. The association proved to be different from one language to another with Arabic taking the lead. The degree of association between mastery of ethnic languages as mother tongues and their preference appeared to be especially remarkable among the Southern group. This confirms our finding that southerners do highly value their own languages viewing them as important symbols of ethnic identity.

<31>

Tables 7a and 7b gives the relationship between language attitude and mother tongue maintenance among adult respondents.

Table 7a: Language attitude and mother tongue maintenance among group 3 (9 – 19 years, 279 respondents, in absolute numbers)

|

Mother tongues of respondents |

||||||||

|

Language preferred |

Arabic |

Beja |

Northern |

Southern |

Nuba Hills |

Darfurian |

Others |

Total |

|

Arabic |

39 |

3 |

6 |

9 |

6 |

24 |

1 |

88 |

|

Beja |

0 |

10 |

|

|

10 |

|||

|

Northern |

2 |

21 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

28 |

||

|

Southern |

2 |

55 |

57 |

|||||

|

Nuba Hills |

3 |

39 |

42 |

|||||

|

Darfurian |

6 |

27 |

33 |

|||||

|

Others |

5 |

2 |

9 |

5 |

21 |

|||

|

Total |

57 |

15 |

27 |

75 |

45 |

57 |

3 |

279 |

Table 7b: Language attitude and mother tongue maintenance among group 3 (9 – 19 years, 279 respondents in %)

|

Mother tongues of respondents |

||||||||

|

Language preferred |

Ar. |

Beja |

Northern |

Southern |

Nuba Hills |

Darfurian |

Others |

Total |

|

Arabic |

68.42 |

20 |

22.22 |

12 |

13.33 |

42.11 |

33.33 |

31.54 |

|

Beja |

66.67 |

3.58 |

||||||

|

Northern |

3.51 |

77.78 |

2.67 |

1.75 |

66.67 |

10.04 |

||

|

Southern |

3.51 |

73.33 |

20.43 |

|||||

|

Nuba Hills |

5.26 |

86.67 |

15.05 |

|||||

|

Darfurian |

10.53 |

47.37 |

11.83 |

|||||

|

Others |

8.77 |

13.33 |

12 |

8.77 |

7.53 |

|||

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

<32>

Table 7b shows that a significant relationship was present between language preference and mother tongue retention among members of the third age group. The association was found with Chi square = 780.58383, df = 36 P< 0.00000, in that a strong relationship exists between mastery of Arabic and local languages natively and positive attitudes towards them. The results suggest that, compared to what happened in the second and third groups, the association between mastery of ethnic languages as mother tongues and positive attitude towards them is particularly significant. This means that ethnic language maintenance and positive attitude towards them go hand in hand among a vast majority of the vernacular - speaking older generation surveyed. The table also shows that a contradictory relationship was found between positive attitude towards ethnic languages and their mastery natively among a considerable portion of old generation Darfurian. In other words, a good proportion of old-generation Darfurian, who spoke their ethnic languages natively (30%), reported that they preferred to speak Arabic. Preference of Arabic in this case is primarily due to the fact that Arabic is an important key to education, social interaction, and economic success.

<34>

This paper has investigated language attitude among ethnic migrant groups in Khartoum (Sudan). More specifically, the paper discussed language preference among the respondents, reasons for language preference, the language parents preferred their children to speak and the relation between speaking a language natively and attitude towards it. Results suggested that while younger generations preferred Arabic, their older counterparts showed more concern for ethnic languages. However, both generations agreed that they preferred Arabic for educational, economic, social and religious reasons and ethnic languages for only symbolic issues. Parental attitudes, on the other, revealed that ethnic groups in Khartoum wanted their children to learn Arabic for practical reasons (educational, economic, religious and social) and ethnic languages for symbolic ones (maintaining the group’s ethnic identity). A general discrepancy between positive attitude towards ethnic languages and their actual maintenance was also found among a vast majority of the community surveyed, especially the younger generations.

References

Adegija, E. 1992

‘Survival strategies for minority languages: a case study of Oko.’ International Journal of the Sociology of Language 102:153-73

Adegija, E. 1994

Language Attitudes in Sub-Saharan Africa. Levedon, Philadelphia, Adelaide: Multilingual Matters

Brown, H. D. 1994

Principle of Language Learning and Teaching. Cliffs: Prentice. Halls

Fardevs, K. 2004

‘Ethnic vitality, attitudes, social network and code-switching: the case of Bosnian-Turks living in Sakarya, Turkey.’ International Journal of the Sociology of Language165:59-92

Fasold, R. 1987

The Sociolinguistics of Society. Oxford: Basil Blackwell

Gardner, R.C. and W.E. Lambert 1972

Attitudes and Motivations in Second Language Learning. Rowely Mass: New Bury House Publishers

IGAD 2004

Protocol Between The Government Of The Sudan & The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement On Power Sharing. http://www.sudanmfa.com/Protocol1.htm (March 7, 2005)

Miller, C. and A. Abu Manga 1992

Language change and national integration in Sudan. Khartoum: Khartoum University Press

Mugaddam, A.H. 2002

Language Maintenance and Shift in Sudan: the case of ethnic minority groups in greater Khartoum. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Khartoum

Richards, J., J. Platt and H. Weber 1985

Longman Dictionary of Applied Linguistics. Harlow: Longman

[1] Special thanks and appreciation are due to Prof. Dr. Geritt Dimmendaal of the University of Cologne, Prof. Dr. Al-Amin Abu Manga of the University of Khartoum, Ashraf Abdelhay, the anonymous reviewers and Dr. Helma Pasch for their help and encouragement.

Lizenz

Empfohlene Zitierweise ¶

Mugaddam ARH (2005). Language attitudes and language shift among ethnic migrants in Khartoum. Afrikanistik online, Vol. 2005. (urn:nbn:de:0009-10-1814)

Bitte geben Sie beim Zitieren dieses Artikels die exakte URL und das Datum Ihres letzten Besuchs bei dieser Online-Adresse an.

Volltext ¶

-

Volltext als PDF

(

Größe:

191.4 kB

)

Volltext als PDF

(

Größe:

191.4 kB

)

Kommentare ¶

Es liegen noch keine Kommentare vor.

Möchten Sie Stellung zu diesem Artikel nehmen oder haben Sie Ergänzungen?

Kommentar einreichen.